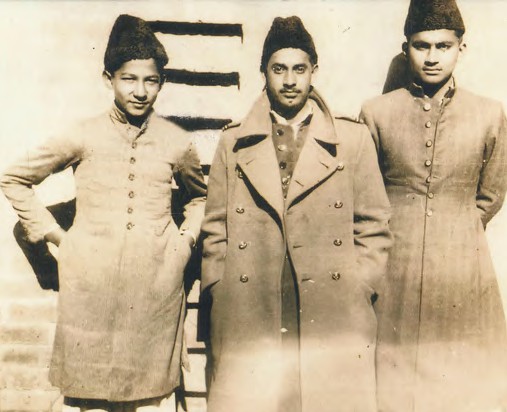

Left to right: Sahibzada Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rta), Deputy Muhammad Latif, the author. (Author’s collection)

Left to right: Sahibzada Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rta), Deputy Muhammad Latif, the author. (Author’s collection)

I have a photograph at home which was taken on the northern veranda of the lower portion of Darul Barakat, the home of Syeda Umme Tahir in Darul Masih, Qadian.1 The three people in the photograph would all go on to serve as pilots. On the left stands Sahibzada Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rta) who was 14 years old when the picture was taken, in the center, dressed in his Air Force uniform is Deputy Muhammad Latif aged 23 and I am on the right aged 17.

I have chosen to describe Sahibzada Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rta) (who later became the Fourth Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community) as a pilot because one of the meanings of this word is to ably and successfully command and control an organization or movement. And as the 21-year-period of his khilafat testifies, he led and guided the organizational, social, educational, moral and spiritual needs of the community with unparalleled patience, strength, courage, steadfastness and zeal.

The other two individuals in the photograph, Deputy Muhammad Latif and myself, merely became pilots of airplanes. However, due to the infinite grace of Allah, in 1947 both of us had the honor of serving the community by flying a small fleet of aircraft that the community owned. The two of us saw many divine signs during this period and for that too we were extremely grateful to Allah the Exalted. I will mention these signs in greater detail later on.

Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih II (ra), the Second Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, was not only an intelligent, attentive, brave, steadfast and far-sighted individual, he was also a peerless leader. He realized long before Partition that because Qadian was situated amid villages which were home to Sikh hardliners, if the law and order situation deteriorated at the time of independence, it was possible Qadian’s links with the outside world could be severed with railway networks, roads, postal services and telephone lines likely to be out of commission for extended periods. Hence, he felt the community needed to acquire at least one small airplane to avoid becoming completely isolated.

It is possible that Huzoor was influenced by the memory of the attack against his great-grandfather, Mirza Ata Muhammad, in which extremist Sikh elements raided 85 villages that belonged to him in the environs of Qadian and took possession of them, leaving only Qadian under his ownership. A group of Sikhs known as the Ramgarhia2, later entered Qadian and captured it too. They created great havoc in the town, destroyed many mosques and houses and forced Huzoor’s forebears into exile to other parts of the Punjab. Eventually, during the last decade of the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Mirza Ata Muhammad was able to return to Qadian and regain five of the 85 villages his family had lost. During these years away, the family’s residence—now known as Darul Masih—fell into decay. Only the frame of the building partially remained; everything else had been looted, stolen or destroyed.

Some 15 years before Partition, towards the end of 1932, a small three-seater plane called a Puss Moth came to Qadian. The plane landed on a large field to the west of the railway station. The owner and pilot of the aircraft was Mr. R. N. Chawla who in 1930 was the first Indian to fly a de Havilland Puss Moth from India to England. He had brought his plane to Qadian with the intention of taking it to London and then flying from there to Karachi to create a record for the shortest ever air journey between the two cities. At the time, the airport in Karachi was considered the center of civil aviation in India.

According to his proposed itinerary, he had to call in at 15 locations on the way to Karachi as his plane was unable to fly more than 300 miles at a time.

In addition, planes in those days did not have the electronic instruments required to navigate at night and there was also the matter of his sleep and rest. Therefore, Mr. Chawla had estimated he would need at least 15 days for this journey. Since he did not have the requisite funds to undertake it, estimated to be Rs 10,000, he had sent out requests for donations to the maharajas, rajas and nawabs of various Indian states. Each donor was asked to give Rs 500 to enable this expedition and enhance India’s prestige in the world.

A copy of this request was also sent to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih II (ra) and Huzoor was the first person to respond to it. Huzoor wrote back to him saying that if he came to Qadian in his plane and took a few members of the community for a ride in it, he would donate Rs 500 to him. And so it was that Mr. Chawla brought his plane and a mechanic with him to Qadian. The plane landed in the town at 7pm on 30 December 1932.

Back then, Qadian had a population of between 3000-4000 people. The entire town came out to see this airplane for the duration of its stay. There were oval semi-circles marked on each side of the landing ground and during the day, they would fill up with spectators. The visit of this plane took place a year before the infamous convention of the Ahrar which saw them enter Qadian and promise to destroy it brick by brick. The convention was held close to the Arya school which was near the railway line.

Mr. Chawla spent the second day of his stay tending to technical and logistical issues before making a test flight. He also met with Huzoor in his office and requested him to come and see the plane for himself. On 1 January at 11am Huzoor, accompanied by a group of khuddam and some elders of the community, went to see the airplane. I was 8 years old then and one of many enthusiastic spectators. As soon as Huzoor arrived, Mr. Chawla made a short test flight and, after landing, he invited Huzoor to come up with him. But for the first flight, Huzoor chose his brother Sahibzada Mirza Bashir Ahmad (ra) and his eldest daughter Sahibzadi Nasira Begum. For the second flight he nominated his youngest brother Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmad (ra) and second daughter Sahibzadi Amtul Qayoom. On the third flight, Huzoor went himself with Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmad (ra).

During Huzoor’s flight the plane did not land after completing its circuit. Instead, it flew higher in an easterly direction and after a while it disappeared from view, causing a wave of anxiety to spread through the crowd. There were people who thought that this might have been a secret plot to abduct Huzoor. Others started to cry, while some began to pray. Their prayers were ongoing when the plane came into sight from the east, flying at a considerable height. There was a sudden sense of relief and various people fell in prostration in gratitude to God. After landing, Huzoor explained that he had asked Mr. Chawla to fly to the Beas River so that he could see the area between Qadian and the river from the air.

The pilot’s seat was at the front of the plane and a wide seat for two passengers was at the back. Huzoor announced a list of names of those who would take turns going up. Each person was given the opportunity to fly for one circuit, which lasted about 7 minutes. The following day—the last one of Mr. Chawla’s visit—some children were also given an opportunity and one adult and two children would go up in turns. My heart yearned for the chance to fly. Perhaps Huzoor sensed something of my desire because suddenly I heard my name called out. I felt like I had won the lottery. In my group there was Sahibzada Mirza Daud Ahmad, later a colonel in the army, Huzoor’s daughter Sahibzadi Amtul Hakeem who was 7 years old at the time and of course myself. The experience made me keen to fly and this desire was fulfilled 10 years later when I was commissioned in the Royal Indian Air Force.

I first joined the Air Force out of necessity. In 1939, when I was 14, I passed my Matriculation exam from Talimul-Islam High School in Qadian with a score of 68 per cent—a first division grade. I had the fifth highest score in my class. I wanted to attend Government College Lahore in the FSc Pre-Medical program, as by then I wished to become a doctor. Despite knowing of my desire, my father had decided that I should become a civil engineer. He had me admitted to an FSc Pre-Engineering course, with the idea that after completing this, I would go to Mughalpura Engineering College, which is now the University of Engineering and Technology. Back then, only 30 boys were admitted to the college every year and of those only four gained entry on an open merit. The rest of the places were reserved for the sons of railway engineers and Public Works Department engineers. Therefore, to be sure of gaining admission, I needed a grade of at least 75 per cent in my FSc exams and this I was not able to achieve.

My father was deeply disappointed with me and remained so for a long time. Left with no other choice, I stayed on at Government College to do my BSc which was then a two-year degree. When I turned 18, and with few options ahead of me as my father was no longer supporting me financially, I decided to join the Air Force. This was a painful period of my life, as I was neither able to become a doctor—which I had so badly wanted—nor was I able to become a civil engineer as my father had wished. Young people today might find this strange, but when I was growing up, it was normal for parents to decide the careers of their children without giving thought to what the children actually wanted.

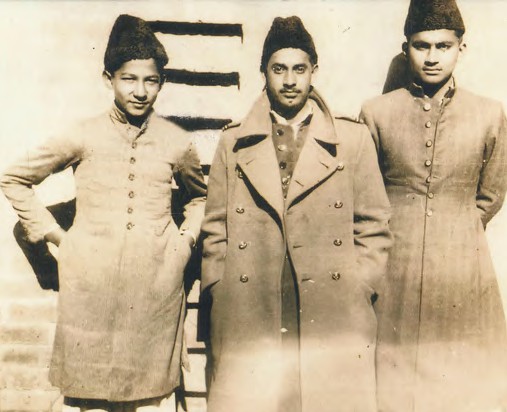

Cadet Officer S M Ahmad. (Author’s collection)

In August 1943, I joined the Air Force as a flight lieutenant. Due to an urgent demand for trained pilots during the Second World War, our flight training was accelerated and completed in short order. We were taught the four stages of flying (basic flying, applied flying, operational flying and air gunnery and weapons) in only 18 months. Nowadays, it takes five years to complete this level of instruction. We received our training at the Air Force bases in Pune, Begumpet, Ambala and Peshawar. Being a bright student, I was selected for the Empire Flying Training Scheme in Canada during our training period in Begumpet. However, I could not go because the program was ultimately cancelled, and I returned to Begumpet after basic training in Bombay (Mumbai).

In 1944 I was commissioned in Ambala. In March 1945, immediately after completing my training in Peshawar, I was sent with the No. 8 Fighter Squadron to the Burma (Myanmar) front. Our squadron was based northeast of Calcutta (Kolkata) at the Baigachi Air Force base in what is now Bangladesh and our job was to protect Calcutta from Japanese air raids. We flew the British Spitfire Model 9 aircraft.

The threat of attack never materialized, so to maintain our sharpness, we had mock dog fights almost every day with the Lightning P-38 fighter planes from a nearby US Air Force base. We nearly always won because in those days the British system of flight training was better than the American one. This is no longer the case and the Americans now lead the way.

The advance of the Japanese from the north into Burma had been halted and Allied forces were beginning to make gains. The Burmese front line was slowly shifting to the south. We had been at Baigachi for only a few months when we received orders to proceed to Mingaladon Air Force base near the Burmese capital Rangoon (Yangon). Since the journey from Calcutta to Rangoon was to be made by sea, we had to leave our fighter planes behind.

The ship that carried us from Calcutta was called the MV Devonshire. On board were numerous officers from different units of the armed forces along with their staff. As there was a danger of ambush by Japanese submarines, we travelled as part of a convoy which included other passenger ships and several navy destroyers for our protection.

This was my first experience travelling by sea. Because our cabins were comfortable, I very much enjoyed the week-long journey. However, when we arrived at Rangoon, there was such chaos and confusion at the port that it took us two days to locate our baggage and find our living quarters. Our accommodation was ghastly, but during the war, things were often that way. The runway of the Air Force base was also in a terrible state, similar to how the Rabwah to Chiniot road used to be many years ago.

The RAF Fighter Squadron 607 had left behind 15 Spitfire Mark VIII airplanes for us at Mingaladon, while they went to our previous base at Baigachi. It was customary that after a six-month stint on the front line, a weary squadron was sent back and a fresh one took its place.

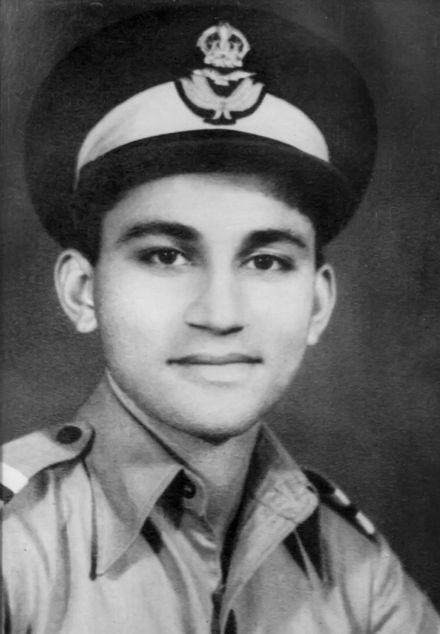

Flt Lt S M Ahmad in 1944. (Author’s collection)

Not only was the runway at Mingaladon in a state of disrepair, the apron was limited in size resulting in a number of accidents. I too once had a collision after making a landing. I was taxiing to my squadron’s apron when a petrol tanker collided with my plane. My propeller was torn off and my fuselage also received some damage. Another time, not long after this, I was hovering immediately above the airport in preparation for a landing, when my drop tank broke off and plummeted to the ground due to a technical fault. It fell almost in the middle of the airport, where 35 parachutists were boarding a Dakota airplane for a mission. At the sound of the explosion, the parachutists ran away and flung themselves into a trench. They only emerged again when their fears had been allayed and they were reassured that the fallen object was a drop tank and not an explosive.

The worst incident that took place during my time there, however, involved an RAF squadron of 16 Spitfire Mark 22s which were used for special missions. These planes could fly above 40,000 feet and required more petrol than other Spitfire models. They were also fitted with state-of-the-art cameras. The squadron’s assignment was to take reconnaissance photos, and these pictures were then supplied to the Army and the Air Force as and when needed. The planes’ only defense was the height at which they flew, as in those days none of the Japanese fighter planes could fly at a similar altitude.

Because space was limited at Mingaladon, and the front line had moved far south of Rangoon, this squadron received orders to change to a more southerly base. The day they were to fly out, all 16 planes were full of gear and topped up with petrol. They were parked in close proximity only 200 feet away from the right side of the runway, wing tip to wing tip. The pilots were drinking tea in a tent behind the aircraft. All of a sudden a Dakota airplane lost control and rapidly spun 45 degrees to the right, ran off the runway and before its pilot could bring it under control, it crashed into the first of these planes which burst into flames. Since the tanks were filled with petrol, all of them caught on fire. We watched this spectacle from the opposite end of the air base and all we could see was a terrible blaze. Within two hours, each of the 16 planes had been burnt to ashes. Thankfully the pilots were safe, but they did not even have a change of clothes because all their personal belongings had been on the aircraft. It was a chilling sight and one which shook us all.

The war soon took a turn for the better. There were victories on almost all fronts and also a marked improvement in our living conditions. But we still thought the fighting would not end by late 1945 or early 1946 because the Japanese continued to hold out resolutely. However, unbeknownst to us, Allied forces were planning a large-scale operation to defeat Japan as soon as possible. As a result, a number of fresh fighter squadrons began arriving at Mingaladon. Despite the military engineers working day and night to build a new and longer runway, space was still tight at the air base.

On 6 and 9 August 1945 the United States of America dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, destroying both of them. The Japanese government collapsed and Japan surrendered. A few days after hostilities ended, the most high-ranking Japanese commander of the region came from Singapore to the Mingaladon Air Base on a Japanese transport plane. We saw him and his delegation surrender arms to his Allied counterpart, General Slim, later field marshal and governor general of Australia. Later, the supreme commander of the Allied forces in South Asia, Admiral Mountbatten, also came to Mingaladon and from there he took a special transport plane to Singapore, where the highest-ranking Japanese commander in South Asia also surrendered arms. Finally, a representative of the Japanese government surrendered to General MacArthur at a ceremony on the American aircraft carrier USS Missouri on 2 September 1945. With that the Second World War came to an end.

Though the war had ended, there were Japanese units still hidden in the dense jungles of Burma who refused to surrender, either because they were unaware that the war was over or for reasons known only to them. For weeks our squadron supported the ground forces that fought against them. This operation was concluded at the end of October 1945. According to official records, I flew the last operational mission on this front.

During our stay in Mingaladon, I was involved in a major accident. On 28 September 1945, the engine of my Spitfire failed during a flight and I had to make a crash belly landing onto a water-soaked paddy field 40 miles south of Rangoon in rainy conditions. By the sheer grace of Allah I was unhurt, but my plane was completely destroyed. It is strange that though two-thirds of Burma is covered by thick jungle, the area around the River Irrawaddy to the southwest of Rangoon does not have a single tree. There are only rice fields for miles and beyond which grow some of the best rice in the world. If it had been a tree-covered area, I might not have survived.

Despite living in Rangoon for eight months, I was unable to visit the grave of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, because this was strictly forbidden to servicemen. On the way to the grave there were a number of signs which read out of bounds to troops. Perhaps the government was afraid that Indian servicemen would be inspired by a zeal for independence by going there.

Some months after the peace declaration, our squadron was sent to Trichinopoly (Tiruchirappalli) air base in southern India. Our ground party with baggage in tow departed for Madras (Chennai) by sea. The others who were taken by air travelled slowly, calling in at Akyab (Sittwe), Calcutta, Jamshedpur, Raipur, Hyderabad Deccan, and Rachnapul. After taking a few days to acclimatize, we settled into our routine of peacetime flying.

There are two things worth mentioning about our stay here. First, as a keen sightseer since I was a child, I would make the most of my Sundays and other time off by touring the area surrounding Trichinopoly. In a few months, I had seen most parts of southern India by train, such as Mysore, Coimbatore, Medora, Madras, Bangalore (Bangaluru), Cody Canal, Nandipur, Wellington, Ootacamund (Ooty), Dhanshkody and so on. I was unable to go to Goa because it was still a Portuguese colony, though after Partition, India annexed it from Portugal. During these visits, I saw many south Indian temples and palaces. In this way, I learned a lot about the culture of south India and about Hindu religion and philosophy.

Second, in February 1946, there was a mutiny on a group of Royal Navy vessels anchored in the port of Bombay. Rebel Indian sailors took their ships out to sea and some of them also killed the English officers on board. To crush this revolt, the Navy sent a company of fighter planes. Our squadron was also summoned to Bombay so that if needed, we could attack the mutineer ships. On the way to Bombay’s Santa Cruz Airport via Hakimpet, my airplane had a small accident for which I had to stop in Hakimpet for repairs. The rest of the squadron continued to Bombay. What had happened was that during my landing the tail wheel collapsed because the locking pin had broken. The lower rudder was also damaged and it took a few days to have it repaired. During my short stay, I spent a few days at the home of Seth Abdullah in Hyderabad Deccan whose hospitality, piety and goodness impressed me deeply.

By chance, certain faculty members of Talimul-Islam College in Qadian were, at the time, being trained at the RAF Technical Training School (TTS/ NTTS) in Hyderabad Deccan at the suggestion of Sahibzada Mirza Nasir Ahmad (ra). They included Chaudhry Muhammad Ali who was later promoted to Professor of Psychology at TI College, Fazal Ahmad who went on to become the inspector general in the Indian Police Service and possibly Master Fazaldad, later a senior staff member at TI College. I met with them when I went to the RAF TTS to get help in fixing the broken rudder. Once my plane was repaired, I flew from Hakimpet to Bombay’s Santa Cruz Airport where I learnt that the Navy had subdued the mutiny and our squadron returned to its base in Trichinopoly. I was reminded of this in 2009 when I received a book published by the British company which made the Spitfire. The book listed every Spitfire which had ever been involved in an accident, regardless of its model or the extent of damage it had received. I learnt that the same airplane whose rudder had been broken was later in service for three years with the Indian Air Force. It was then retired and placed in the Indian Air Force Museum. Many years later, the RAF museum in England needed a Model-14 Spitfire and purchased the retired airplane at a great cost from India. It now sits in the RAF museum in London. If Allah wills, I hope to visit London again someday, a city I have been to many times and have my photo taken next to this airplane. In addition to this, the book also mentioned in detail the other three Spitfire accidents I was involved in: that is to say, the ground collision between a petrol tanker and my plane, the time my drop tank fell off my plane and my crash belly landing when my engine failed, including the reason for the engine failure.

We had been in Trichinopoly for about eight months when we received orders that three squadrons of the Royal Indian Air Force, including ours, were being sent to Kolar Air Force base. Kolar is a district in the south Indian state of Karnataka which is known for its gold fields. The base was situated about 60 miles to the east of Bangalore. We usually visited Bangalore about once a week, sometimes for work and at other times for recreation.

A Spitfire, similar to the author’s, in the RAF Museum, Grahame Park Way, London. (Mr. Bilal Atkinson 2016)

1 The home of the Promised Messiah (as).

2 The Ramgarhia are a Sikh community belonging to the Punjab. Members of the Ramgarhia were traditionally carpenters but also pursued other artisan occupations like stonemasonry. [Publishers]