(Al-Furqan, 25:78)

After refuting the misstatements which Maulawi Muhammad Ali has made in his account of the split, I proceed next to give a true account of the events which led to it; so that, on the one hand Ahmadis who are not yet acquainted with the truth about the split may become acquainted with it and, on the other, those who have been thrown into a state of indecision by this spectacle of dissensions in the Community, who therefore hesitate to join the Ahmadiyya Movement even though they entertain sympathy for it may become acquainted with the true story of the split, and be in a position to judge the Movement and make up their minds about it.

It is inevitable in the case of every spiritual movement, that among its followers there should be some who enter it because they believe in its truth but who nevertheless are very superficial in their judgement and convictions. The truth does not seem to go very deep into their hearts. In the first ebullition of their zeal they seem to go further than many a sincere follower. But as their faith strikes no deep root, they are always liable to cut themselves off from the main body of the movement, and to reject the truth at any time. A number of such persons joined the Ahmadiyya Movement founded by the Promised Messiah (as), and they brought about not only their own secession but the secession of many others from the ranks of the Movement.

In my opinion the person at the root of these dissensions is Khwaja Kamaluddin who has attained great fame because of his connection with the Woking Mission. Maulawi Muhammad Ali is only a disciple who joined Khwaja Sahib a long time after.

This view—that the story of Ahmadiyya dissensions goes back to Khwaja Kamaluddin—has often been expressed by our side. It was Khwaja Sahib, we have said, who first began to have doubts about the Promised Messiah (as), which doubts he communicated to Maulawi Muhammad Ali upsetting Maulawi Sahib in consequence. In view of this it seems to me that to Maulawi Muhammad Ali’s attempt to connect Ahmadiyya dissensions with Zahiruddin—this has been fully discussed by me in Part I of this book—is only a counterblast to our view which connects the dissensions with Kamaluddin.

There is no doubt that when Khwaja Kamaluddin entered the Movement he did so as a sincere believer in its truth. But this is quite different from saying that it was a deep conviction of the truth of the Movement which made him join its fold. The cause of his joining the Movement was that he had at that time begun to feel dissatisfaction with Islam, and to feel an attraction towards Christianity. But as it is hard to part with one’s family and friends, Khwaja Sahib fell a victim to a most intense mental conflict. It was therefore a great relief to him to see how the exponents of Christianity cowered and fled before the onslaughts of the Promised Messiah (as). He discovered that even within the fold of Islam it was possible for one to plant his feet firmly, and to resist the attacks of Western learning and science. As this release from a terrible mental conflict he owed to the Promised Messiah (as), he quickly joined the ranks of his followers. Considering his mental attitude at the time, it cannot but be said that he joined the Movement with a sincere heart. It is natural for one, who has been saved from a great disaster, to hold his saviour as high as he possibly can. It was, therefore, natural that Khwaja Sahib came to believe in the claims of the Promised Messiah (as). But it appears he never entered into a close study of those claims. His faith had its roots in gratitude to the Promised Messiah (as) who had saved him from becoming a Christian and from the pangs of separation from relatives and friends. It is clear that such a faith could not have lived for a very long time. With the lapse of time and the consequent fading from his memory of the days when he stood between Christianity and Islam—when, on the one hand, the many captivating allurements of Christianity were tempting his mind, and, on the other, the fear of parting from everything dear was tearing his soul—his faith began to decay, so much so that at the time of the prophecy relating to Abdullah Atham he very nearly turned an apostate. In 1897 there was held at Lahore a Conference of Religions. The Promised Messiah (as) was invited to write a paper for this Conference. It was Khwaja Kamaluddin himself who brought the invitation. The Promised Messiah (as) in those days was suffering from an attack of diarrhoea, but, nevertheless, he undertook to write this paper. When, by the Grace of God, the paper was finished, the Promised Messiah (as) made it over to Khwaja Sahib. But Khwaja Sahib gave expression to a feeling of disappointment saying that the paper would not meet with appreciation at the Conference. In fact it would merely invite derision. But God revealed to the Promised Messiah (as) that his paper would prove the best of all the papers at the Conference. Accordingly, he wrote out a notice announcing the revelation. This notice also, the Promised Messiah (as) made over to Khwaja Sahib directing him to have it printed and posted in advance all over the city of Lahore. He also spoke many a word of comfort and encouragement to Khwaja Sahib. But as Khwaja Sahib had already decided that the paper was worthless, he gave no publicity to the notice nor did he let anybody else do this. At last when some people reminded him of the command of the Promised Messiah (as), and pressed him to publish the notice, he managed to have a few copies of the notice posted secretly on the walls of the city, and they were put so high that they could not easily come to the notice of the public. But now that they had been put, the Promised Messiah (as) could be truthfully assured that his command had been carried out? For, in the opinion of Khwaja Sahib, the paper regarding which God had been pleased to foretell that it would prove the best in the Conference, was not good enough to be read at that great gathering. At last arrived the day which had been fixed for the reading of the paper. The reading commenced, and before many minutes had passed, a complete stillness prevailed and a spell fell upon the audience. The allotted time was over but the interest of the audience was unabated. More time was given but the addition proved inadequate. Then, at the request of the audience, the Conference was extended by one clear day to enable the reading of the paper to be concluded. Friend and foe declared with one voice that the paper by the Promised Messiah (as) was undoubtedly the best that had been read at the Conference, and thus what had been foretold by God was duly fulfilled. But this great prophecy was robbed of its effect through the lukewarm faith of Khwaja Sahib. For, now all we can do is to recount the history of those days, but all the difference in the world would have been made, had the prophecy been published duly and well before the time came for its fulfilment. The importance which such a publication would have given to the prophecy can easily be imagined by everybody. This and other incidents of a similar nature go to prove that Khwaja Kamaluddin had failed to realise the true inwardness of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and his adherence to the Movement was really due to gratitude for benefits derived from the Promised Messiah (as). For example, the opponents of the Promised Messiah (as) at various time brought law suits against the Promised Messiah (as), Khwaja Sahib used to look after these suits on behalf of the Promised Messiah (as). During all these transactions he exhibited many a sign of weakness of faith, but a reiteration of those signs would not be appropriate at this place.

In 1905, a suggestion was made by The Watan that if The Review of Religions should refrain from making any mention of the Promised Messiah (as), and devote itself solely to propagating the general principles of Islam, then it would be possible for the general body of Muslims outside the Ahmadiyya Community to support and subscribe to The Review.

Khwaja Sahib at once consented to act on the suggestion, and proposed that The Review should have an appendix attached to it and in that appendix should be published matters connected specially with the Ahmadiyya Movement, the body of the magazine to contain only topics connected with the general principles of Islam. The proposal raised such a storm of protest that at last Khwaja Sahib had to give in and the whole idea had to be abandoned. But this proposal by Khwaja Sahib and Maulawi Muhammad Ali served to encourage one Dr. Abdul Hakim, who had already for some time been labouring under the influence of certain heterodox notions, to initiate correspondence with the Promised Messiah (as). The apparent occasion of the correspondence was the understanding which Khwaja Sahib had entered into with the editor of The Watan with regard to The Review of Religions, but in the course of this correspondence were formulated for the first time certain doctrines which subsequently proved to be the basic principles of the Lahore seceders.

Dr. Abdul Hakim wrote his first letter to the Promised Messiah (as) early in 1906, the purport of which was as follows:

That it should be legal for us to offer prayers behind other Muslims, except such as designated us as kuffar.

That the proposal made by Khwaja Kamaluddin and Maulawi Muhammad Ali with regard to The Review of Religions should be accepted and carried out.

That the claims of the Promised Messiah (as) were subordinate to Islam and not fundamental to it; the presentation of his claims, therefore, should not be allowed to stand in the way of propagation of Islam.

That in the order of presentation some scientific method should be followed. The more general principles pertaining to Shirk (polytheistic tendencies) and Bid‘at (innovations) should be presented to the public before the presentation of the personal claims of the Promised Messiah (as).

That undue prominence should not be given to the question of the death of Jesus. Other doctrines of Islam should also receive due attention.

That the moral tone of the Ahmadiyya Community should receive special attention for its improvement.

That the Ahmadiyya Community had proved slack in the work of propagation, which duty required their special attention. They had ceased to show ordinary courtesies to non-Ahmadis, although remissness in propagation was primarily their own fault.

That the true guides to Islam were healthy instincts and a sound teaching, not merely prophecies. It was, therefore, the greatest temerity to speak of the teachings of the Holy Quran as dead. (The reference here is to what was said in reply to the suggestion made by The Watan, viz. that all omission of the Promised Messiah (as) would leave only a dead Islam for presentation to the world—Author). If Ahmad and Muhammad were not different in their teachings, why should the teachings of Muhammad in the form in which they had been presented to the world during the last 13 centuries be now regarded as obsolete. There could be no greater insult to Islam than to suppose that the mainstay of its life depended upon a personality which appeared in the world thirteen hundred years after the advent of Islam.

That this was an age of learning and much good would have accrued from the presentation of philosophical interpretations of the Holy Quran. The Appendix proposed for The Review of Religions might have been printed separately, and subscribed to exclusively by members of the Community. This arrangement would have increased the circulation of The Review of Religions. But, unfortunately, Ahmadis chose to follow the path of narrow-mindedness, and while non-Ahmadis offered to break down barriers, Ahmadis themselves worked to keep them erect.

In another letter Dr. Adbul Hakim wrote: “What! Do you think that not one out of thirteen crores of Muslims is truly God-fearing and righteous, that the spiritual influence of Muhammad has ceased to work in the entire mass of Muslims, that Islam has become altogether a body without life, that the Holy Quran has altogether lost its influence, that God and Muhammad (sas) and the Quran and the Divinely planted instincts and human reason, have all alike become outworn and useless, so that outside your own Community there remains no righteous person either in the general body of Muslims or in the mass of mankind, and that they have all turned black-hearted, doers of black deeds and inmates of Hell?”

At this place, I do not propose to state what answers the Promised Messiah (as) gave to the questions of Dr. Abdul Hakim. I propose to discuss these questions further on and in more detail. Here I should like only to state what the Promised Messiah (as) wrote in reply: “If you are worried by the question—how can it be that the multitudes who are not members of our Community have no righteous persons among them—then, pursuing the same trend of thought you might also ask whether millions of Jews and Christians who reject the truth of Islam have no righteous persons among them. At any rate, when God has been pleased to reveal it to me that every person who has heard my call and failed to accept my claim, is not to be considered a Muslim, and is answerable before God for it—then under the circumstances, how can it be that I should overlook this Divine command at the instance of a person whose heart is enwrapped in a thousand shrouds of darkness? It is better that I should cut off such a person from the body of my Jama‘at. Accordingly, I hereby and from today excommunicate you from my Jama‘at.”

The immediate effect of this sharp and severe chastisement by the Promised Messiah (as) was that no other member of the Community at the time could gather courage to support and subscribe to the views expressed by Abdul Hakim. But, nevertheless, it would appear that the ideas had already found deep root in the hearts of some members of the Community, and chief among them was Khwaja Kamaluddin. Facts go to show that the faith of Khwaja Kamaluddin at this time had already begun to crumble. His subsequent writings make it clear that he really had fallen a victim to these views of Dr. Abdul Hakim, and today it is an open secret that it is just these views which Khwaja Kamaluddin advocates.

So far as I can judge, Maulawi Muhammad Ali did not at first subscribe to these views. But Khwaja Sahib discerned in him a very useful instrument for the attainment of his purpose. So he persisted in his endeavours to win Maulawi Sahib over to his views. In course of time, he managed to do so and encouraged Maulawi Muhammad Ali to criticize even the Promised Messiah (as). I do think, however, that during the lifetime of the Promised Messiah (as) there was not much slackening of faith in Maulawi Muhammad Ali. But as soon as the Promised Messiah (as) breathed his last, a remarkable change began to come over him. Little things contributed to this change. Maulawi Muhammad Ali had always been of an irritable temper. He never could tolerate anything adverse to his own way of thinking. He was also slow to forget when once he became offended. He would stick at nothing to injure those who differed from him. While the Promised Messiah (as) was alive, he often became annoyed with Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) in matters concerning the Anjuman. When at the death of the Promised Messiah (as) it was proposed to elect Hazrat Maulawi Noor-ud-Deen Sahib as Khalifa, it caused serious umbrage to Maulawi Muhammad Ali. He resented the election, and demanded authority for the institution of the Khilafat. But the unanimity of the Community on the occasion and the general helplessness prevailing at the time restrained him, and led him to enter the Bai‘at of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). Nay more, he himself became one of the signatories of the notice in which it was announced that Hazrat Maulawi Noor-ud-Deen Sahib had been elected Khalifa in accordance with the terms of Al-Wasiyyat (the Will of the Promised Messiah (as)). In spite, however, of this outward allegiance, he remained unconvinced at heart, and in the circle of his friends and associates his conversation often assumed a tone which implied denial of the Khilafat. Thus, gradually he formed around him a party of men who shared his views. The most important person who joined him was of course Khwaja Kamaluddin. Khwaja Sahib had been seeking to win over Maulawi Muhammad Ali to his own views, and the best way of doing so now seemed to be to subscribe to the attitude which Maulawi Muhammad Ali had assumed with regard to the Khilafat. Accordingly not fifteen days had passed after the death of the Promised Messiah (as) when, on a certain occasion in the presence of Maulawi Muhammad Ali, Khwaja Kamaluddin addressed me saying, “Miyań Sahib, what is your opinion regarding the powers of the Khilafat?” To this I replied that the time to decide the question of powers was when the Bai‘at had not yet been sworn. When the Khalifa had declared in clear words that after entering into his Bai‘at we would be required to render him complete obedience, when we had heard these words and had still entered into his Bai‘at what right had we, who had thus chosen to be servants, to determine the powers of the master? On hearing this reply, Khwaja Sahib changed the topic of conversation.

About this time, Maulawi Muhammad Ali began to entertain certain grievances against our mother, Hazrat Ummul Mu’minin (mother of the faithful). Whether these were real or imaginary, Maulawi Muhammad Ali took them to heart. He went even so far as to refer to them in the columns of The Review of Religions (Urdu edition). As I had always been a staunch supporter of the Khilafat idea, his prejudiced mind induced Maulawi Muhammad Ali to think that my support to the Khilafat arose from the fact that I aspired to become Khalifa myself. To his opposition to the Khilafat idea, therefore, he now added opposition to members of the Promised Messiah’s (as) family, especially opposition to me. To promote this opposition he even had recourse to steps enumeration of which is neither possible nor desirable at this place.

In the meantime, the days of the Annual Gathering (Jalsa) approached near and friends of Maulawi Muhammad Ali made special preparation for addresses on the occasion. In these addresses they sought one after another to impress upon the Community that the real successor and Khalifa appointed by the Promised Messiah (as) was no other than the Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya (Central Ahmadiyya Association), of which Maulawi Muhammad Ali and others were the trustees.

Obedience to them therefore was obligatory upon the whole Community. This subject was stressed so much and by so many speakers that some of those present were able to guess at the real purpose of the speakers which they realised, was to depose Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) from his office and to inaugurate their own Khilafat. For out of the fourteen members of the Sadr Anjuman about eight were particular friends of Maulawi Muhammad Ali. Some of them had made common cause with him, and others supported him because of the general esteem in which they held him. The Khilafat of the Sadr Anjuman, therefore, virtually meant the Khilafat of Maulawi Muhammad Ali who had managed by intrigue to secure the undivided control of all its affairs. On account of an urgent business, I could not be present at all the speeches delivered on the occasion of that year’s Jalsa, and even when I was present, my attention was not drawn to this aspect of those speeches. As subsequent events showed some of those present were able to guess the underlying plan of the speakers. The question which now began to be discussed in the circles of their friends were: What were the proper functions of the Khalifa? Who held the supreme authority over the Community, the Sadr Anjuman or Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra)? No suspicion of what was going on, however, had yet entered my mind. The Community had become divided into two rival camps. One was endeavouring to convince the rank and file that the proper successor of the Promised Messiah (as) appointed by the Promised Messiah (as) himself was the Sadr Anjuman. The other opposed this view and held to the terms of their Bai‘at. All this time, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra), had no knowledge of these discussions, and I too was quite unaware of them. At last, Mir Muhammad Ishaq submitted in writing certain questions to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) and requested that light might be thrown on the subject of Khilafat. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) sent the questions to Maulawi Muhammad Ali for reply. The reply which Maulawi Sahib wrote proved amazing to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). For, in that reply the status of the Khalifa had been so far reduced as to leave him little else to do with the Community save to accept the Bai‘at from new entrants into the Community. Upon this Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) ordered that a large number of copies of the questions should be made, and that these should be circulated in the Community with a request for reply. He also appointed a date (31st of January, 1909) when representatives of the Community from different centres were asked to assemble at Qadian for the purpose of a conference. I continued however to have no idea of the trouble until I had the following dream.

I dreamt that there was a house divided into two parts. One part was complete, while the other was yet unfinished. The unfinished part was being-roofed over. The rafters had been laid but the planks had not yet been nailed. Upon the rafters was placed some straw and near it stood Mir Muhammad Ishaq, my younger brother Mirza Bashir Ahmad, and another boy, a relative of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra), named Nisar Ahmad, who has since left the world—(may God shower His mercy upon him). Mir Muhammad Ishaq held in his hand a match-box, and it seemed he was about to strike a match in order to set fire to the straw. I tried to stop him, saying that the straw, it was true, would ultimately be burnt, but time for it had not yet come. He therefore should not set fire to it yet, lest some of the rafters also should get burnt along with the straw. This made him desist from the attempt, and I walked away. I had not gone far when I heard a noise, and turning back I saw Mir Sahib hurriedly striking match after match and trying to set fire to the straw. He was in a hurry fearing I should return and stop him and owing to this haste the matches were extinguished as soon as lighted. Upon seeing this I ran back with a view to stopping him, but before I could reach the place, one of the matches had lit up, and with it Mir Muhammad Ishaq was able to set fire to the straw. I ran up and trampled upon the straw, and managed to extinguish the fire but even so, the ends of some of the rafters were burnt. I mentioned the dream to my esteemed friend, Maulawi Sayyid Sarwar Shah Sahib. He smiled and said, “Bless you! the dream has already been fulfilled.” He told me certain things, but either he did not know them well or he could not at that time describe them fully to me. I then wrote out the dream and submitted it to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra). He read and replied to me in a note that the dream had already been fulfilled. Mir Muhammad Ishaq had submitted certain questions in writing, which, it was feared, might create trouble and prove a trial for some. This was the first time that I came to know of the trouble that was afoot, and I came to know of it through a dream. After this, I received my copy of the questions which Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) had ordered to be circulated for reply, and I began to offer special prayers to God to solicit His guidance for a correct answer to those questions. It was true that I had already entered into Bai‘at with Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) and there was no doubt that my reason had convinced me of the need of Khilafat. Nevertheless, I began to think about the subject with a perfectly open mind, and began to pray to God that He should guide me to the truth. The day gradually came near when replies to the questions had to be submitted to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). I wrote down whatever I could think of at the time, on the subject, and made over my reply to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra). But still my heart was not at rest. I longed that God should Himself show me the way. God is my witness how sore and trying those days proved to me. I spent days and nights in sorrow and grief, fearing lest I should commit a mistake and displease my Master. But in spite of my anguish and restlessness, no kind of light came to me from God.

At last came the night on the morrow of which the appointed meeting was to have been held. People gathered from all sides and their faces showed they were fully alive to the momentous nature of the day that was to dawn on the morrow. It appeared that every effort had been made to convince the people who came from outside that the proper representative of the Promised Messiah (as) was none other than the Anjuman and that the Khalifa was simply to accept the Bai‘at. All along their journey to Qadian, special efforts had been made to convince them that the existence of the Community was at stake, that a few wicked people had raised the question in order to serve their private ends, and that their aim was to secure control of the purse of the Community in order to enable themselves to act in accordance with their own sweet will. In Lahore, a special meeting of the Ahmadiyya Jama‘at was convened by Khwaja Kamaluddin at his own house, and it was explained to members that the entire Movement was in danger, that the proper representative of the Promised Messiah (as) was none other than the Anjuman and that if this view was not accepted it would ruin the Community and destroy the whole Movement. Signatures were also obtained from the people to a statement to the effect that according to the writing of the Promised Messiah (as) the Anjuman was his proper successor. Only two men, viz. Hakim Muhammad Husain Qureshi, Secretary Anjuman Ahmadiyya, Lahore, and Babu Ghulam Muhammad, foreman, Railway Office, Lahore refused to sign the statement. They said that they had sworn the oath of allegiance to a person who was superior to them in learning and piety and who exceeded them all in his devotion to the Promised Messiah (as). They would, therefore only follow that which he would be pleased to command. In short, the statement was drafted and signed, the people had been instructed, and Khwaja Kamaluddin came fully prepared to Qadian. Since it was a matter which concerned their faith, and the rank and file had been assured that a false step at this stage would condemn the Community to perpetual ruin, there was a great stir of feeling in the Jama‘at. Many were ready to lay down their lives for the sake of the cause and some made bold even to declare that, if the Khalifa came to an unsatisfactory decision, he would be deposed from the Khilafat forthwith. Others waited in silence for the Divine decision. Still others displayed enthusiasm in support of the Khilafat and were ready to make every sacrifice for the sake of maintaining its authority. Speaking generally, nearly all the people who had come from outside, and who had been under the instruction of Khwaja Sahib and his friends, as also a portion of the residents of Qadian, were inclined to hold the view that Anjuman was the proper successor of the Promised Messiah (as). A majority of the residents of Qadian no doubt supported the authority of the Khilafat.

Those who have subsequently joined the ranks of the Movement and have not had occasion to witness the pain and suffering which the Promised Messiah (as) had had to endure for its establishment, nor have they known of the travails through which the Movement had to pass in order to attain to its present height cannot realise the mental agony through which Ahmadis passed in those days. With the exception of a few selfish individuals, the whole of the Community, no matter what beliefs or doctrines they held was, as it were, in a state of living death. Every one of us seemed to prefer that he and his kith and kin should be put to death with the most cruel tortures rather than that they should cause a dissension in the ranks of the Community. That day the earth, in spite of its wide expanse, seemed all too cramped for us and life, in spite of all its comforts, seemed worse to us than death. As the night advanced and morning drew near, my restlessness increased and I moaned and prayed to God saying, “Lord; it is true I have preferred one opinion to another. Nevertheless, my Lord, I do not wish to be one of the faithless. Be Thou my guide, and lead me to the right course. I desire not to prefer my own opinion. I seek the Truth, and long for the Right.” In the course of my prayers I resolved that if God did not vouchsafe to me any reply I would not attend the meeting and save myself from being a party to any dissension. When my resolution reached this stage, the door of Divine mercy opened. God covered me with the mantle of His grace, and the following words involuntarily came upon my lips:

(Al-Furqan, 25:78)

Say, “What cares my Lord for you, unless you prostrate yourselves humbly before Him.” When these words came, I experienced a new illumination. I was convinced that my view of the question was the correct one, because in the verse the word Qul meaning “Say” signified that I was to speak these words to others, from which it followed that it was not me but those who held views contrary to mine with whom God was displeased. It was then that I rose and offered thanks to God. My heart was at ease, and I waited for the morning.

It is common with Ahmadis that they get up some time during the latter part of the night to perform Tahajjud prayers. But this night was specially remarkable in this respect. Many there were who spent the whole of it in a vigil. As early as the time for Tahajjud prayers, most of them had assembled in the Masjid Mubarak to pray to God for guidance and help. On this occasion, so many and so moving were the prayers offered that I am sure they reached and must have moved the Divine Throne. Nothing was heard save the wailing and sobbing of supplicants. Every eye was turned to the Lord of the universe and to no one else. Every hope leaned on the Great God and on no one else. At last came the morning, and with it began preparation for the morning service. There was some delay in the arrival of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). Friends of Khwaja Sahib were glad of the opportunity and availed themselves of it by addressing the people once more. I was in my house pacing the yard, waiting for the service to begin. Our house adjoins the mosque. The voice of Shaikh Rahmatullah Sahib reached my ear. He said, “God’s wrath! A few designing men want to ruin the Community by raising a stripling to the Khilafat.” My mind at the time was a total blank. I could not therefore see that myself was the stripling referred to. I continued to ponder over the words in amazement, and I could not guess their meaning. Subsequent events, however, demonstrated that his fears were not justified. Khulafa’ are not appointed by men. God however, had already resolved that one day this same stripling upon whom they looked with such contempt would become Khalifa and through him would be carried the message of the Promised Messiah (as) to the four corners of the earth. God had resolved to prove that He was All-Powerful, that He stood in no need of help from any quarter. These men who were trying to fight the Divine plan seem to have had an instinctive premonition of events, which had already been decreed by God. Thus, until the arrival of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), the question was well talked over in the mosque, and every aspect of it was explained to the congregation. At length, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) came and began the service. The text he chose for recitation was the chapter entitled “Buruj” As he came upon the verse:

(Al-Buruj, 85:11)

“Those who cause the believing men and the believing women to fall into trial and repent not, for them is the punishment of hell and the torment of burning.” A strange influence fell upon the whole congregation. It seemed as though the verse had been revealed just then. The heart of every worshipper was filled with the fear of God. The mosque seemed a hall of mourning. In spite of the utmost effort to control, such loud sobs and moans involuntarily escaped many worshippers that never perhaps had a mother wept more bitterly over the death of her only son. Not a man was there who did not weep. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) himself had his voice choked by the intensity of the emotion. And such a strange feeling seemed to have passed over the whole people that Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) recited the verse for a second time. Then every member of the congregation seemed half-dead and save the few recalcitrant spirits that were there, all felt a softening of heart and a renewal of faith and a complete absolution from selfish thoughts. It was a heavenly sign that we witnessed that day, a providential succour which had been vouchsafed to us. The service over, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) retired to his house, and some men produced a writing of the Promised Messiah (as) and endeavoured again to persuade the people that after the Promised Messiah (as), the Anjuman alone was the rightful successor. The hearts of the people at the time were filled with the fear of God. They were unaware of the real intention of the writing. They were, therefore, all the more intensely moved to find that the Promised Messiah (as) had decided that after him the Anjuman was to be his successor. But nobody seemed to be aware why it was that such feeling was spreading over the people, and what was going to spring from behind the curtain. At last time came for the meeting and people were asked to assemble on the roof of Masjid Mubarak (the mosque which adjoins the house of the Promised Messiah (as), and in which he used to perform the five daily prayers). Dr. Mirza Ya‘qub Baig came to me and requested me to go to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) and tell him that there was now no apprehension of any trouble, as it had been explained to every body that the rightful successor of the Promised Messiah (as) was the Anjuman. I perceived the hollowness of what he said and thought it best to remain silent. But Dr. Ya‘qub Baig himself went to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra). I too had reached there. No sooner did he come then he submitted to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) saying, “Blessing! All the people have had it explained to them that the Anjuman is the proper successor of the Promised Messiah (as).” To this Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) replied, “Which Anjuman? The Anjuman which you think is proper successor of the Promised Messiah (as) has no status under rules.” It was then that perhaps for the first time the party of Khwaja Sahib realised that the matter was not as easy as they had supposed. Before this, although they had anticipated every possible difficulty and prepared the people, in the event of any opposition from the Khalifa, to meet and overrule him, yet they seemed to entertain the hope that Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) would lend his support to their side, and decide the question in accordance with their views. It was because of this that many members of their party who believed in the goodness of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) used to declare, “Thanks to God, the question has come up for decision during the time of a man as selfless as Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). Had it come up later, who knows what it would have led to?”

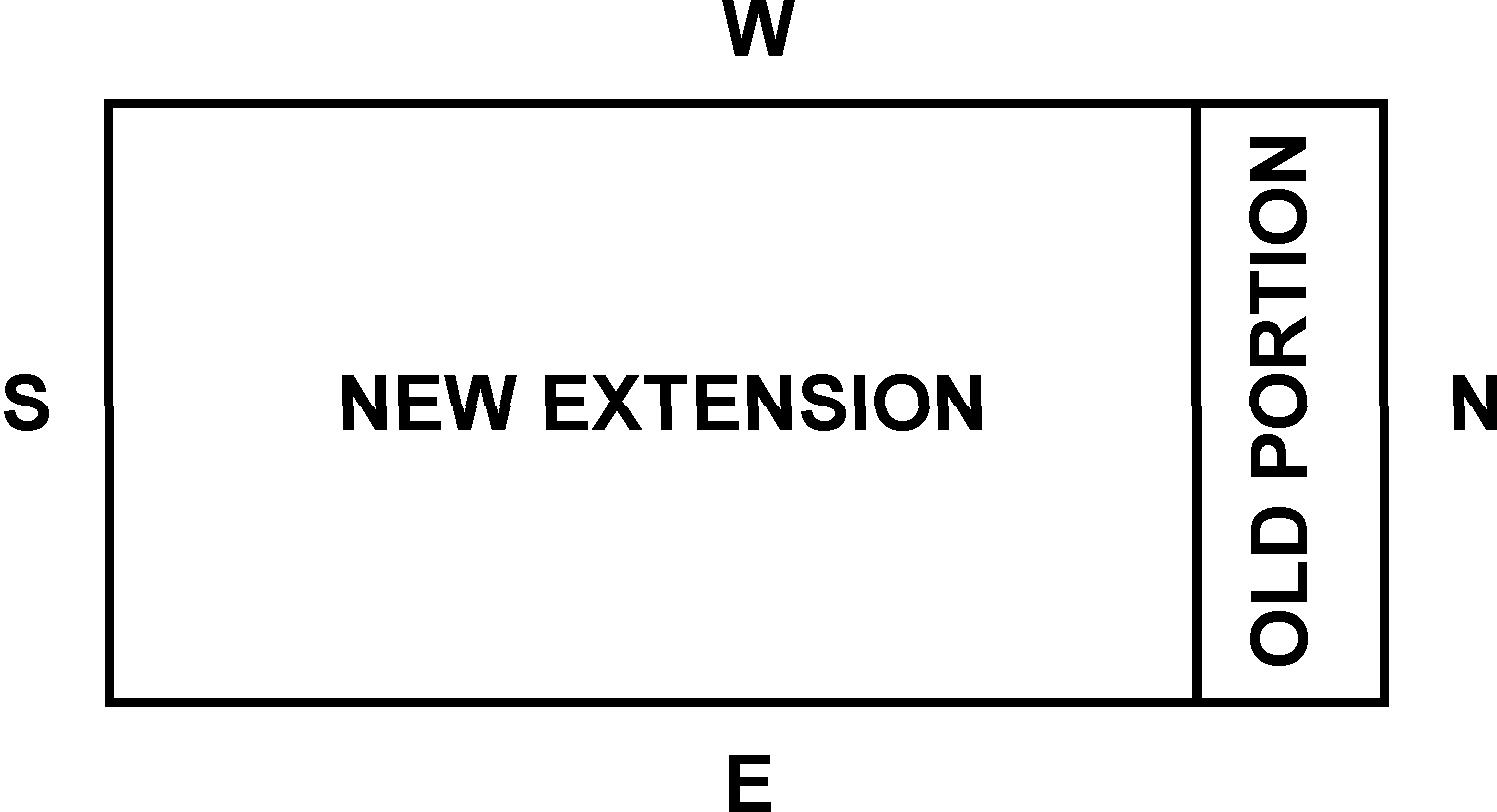

After the people had gathered, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) came to the mosque. The gathering numbered between 200 to 220 men. Most of them were delegates from different Ahmadiyya associations. To an ignorant observer this small gathering of about 200 to 250 men on the bare roof of a mosque without a carpet or mat might have seemed a trifling even a contemptuous sight. But they were men whose hearts overflowed with faith in God and an unquestioning trust in His promises. The gathering was the most momentous in the history of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and therefore in the history of the peace and progress of the world. The superficial observer today may well be dazed by the pomp and grandeur of the Peace Conference now holding its sessions in Paris, but far greater in moment was this gathering upon whose decision was to be founded the future course of the history of mankind. The question at issue at this gathering on that day was—what was to be the nature of the organization of the Ahmadiyya Movement? Was it to follow the line pursued by modern parliaments and associations or was it to follow in the footsteps of the Companions of the Holy Prophet (sas)? That day therefore was to decide the fate and future of the whole of humanity. It may be too early yet for people to realise this, but many years will not pass before they will realise that this silent wave of religious enthusiasm was to prove far purer, healthier, and more conducive to the peace of the world than the most spectacular political movements of our time. But to return to the story. The people had assembled over the roof. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) had arrived. They had prepared for him a place somewhere in the middle. But he declined to stand there, and took his stand in the northern part of the roof, the part which had been built by the Promised Messiah (as) himself.1

Standing there he began his speech. He said that the question of Khilafat belonged to the Shariah i.e. the Law of Islam, that the Community could not possibly advance without a Khalifa, that he had been told by God that for every one who should turn apostate, He would give him a Jama‘at of new adherents, that therefore he had little regard for what they might choose to decide, and that through God’s grace it was his firm conviction that He would remain his Helper. Then, referring to the replies of Khwaja Kamaluddin and Maulawi Muhammad Ali, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih continued: “There are people who would tell me that the duties of the Khalifa consist only of leading congregation in the daily prayers and in funeral services and in accepting Bai‘at from new entrants. This is the outcome of ignorance and impertinence; such men should therefore repent and seek forgiveness, for otherwise harm is sure to come to them.” Proceeding further he observed, “You have caused me great pain by your acts and have brought the office of Khilafat into contempt; that is why this morning I did not take my stand in the part of the mosque which has been built by you; I am standing instead in the portion which was built by the Promised Messiah (as) himself.”

As he proceeded with his speech, the entire gathering with the exception of a few hardened souls had their hearts opened, and in a short time those same men who had resolved to see the great Noor-ud-Deen deposed from his office, came to perceive their folly, and turned from being opponents of Khilafat to being its warmest supporters. In the course of his speech, he also found fault with those who had busied themselves with organising meetings in support of the Khilafat, saying that when the Khalifa had himself summoned people to a meeting, they had no business to hold separate meetings of their own and had no authority from the Khalifa for such an action. After he had finished his speech some people requested for leave to address the meeting. There, however, remained little to be said, for the whole gathering excepting only a few individuals had accepted the right view. Nawab Muhammad Ali Khan, my brother-in-law, and I were asked to express our views. We said that the views expressed by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) were the views which we had all along supported and upheld. Next Khwaja Sahib was called upon to speak. He found it expedient to express himself in vague terms.

Then Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) said that these people must renew their oath of Bai‘at, and asked Khwaja Sahib and Maulawi Muhammad Ali to retire and think over the matter, and if they really felt prepared, then alone should they come and take the oath of Bai‘at again. Then turning to Shaikh Ya‘qub Ali, the editor of Al-Hakam who had been the promoter of a meeting in which signatures were taken in support of the Khilafat, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) said that he too had made a mistake and should therefore renew his Bai‘at. Accordingly these three men renewed their Bai‘at, and the meeting was dissolved. At that time, a feeling of satisfaction came to dwell in every heart and those present felt that Providence had saved the Community from a grave crisis. But Maulawi Muhammad Ali and Khwaja Kamaluddin who had just renewed their Bai‘at felt seriously aggrieved, and subsequent events proved that their Bai‘at on the occasion was a mere show. They never sincerely recognised the authority of the Khalifa. It is reported (on the authority of Maulawi Abdur Rahim Nayyar who was in those days on very intimate terms with these gentlemen) that no sooner had they alighted from the roof of the mosque than Maulawi Muhammad Ali spoke to Khwaja Sahib saying, “Today we have been badly insulted. It is something more than I can endure. It is as if we had been beaten with shoes in an open meeting.” One wonders at the sincerity of this man who today poses as the reformer of the Community!

If what, Maulawi Muhammad Ali said on coming down from the mosque were supported only by the uncorroborated testimony of Maulawi Abdur Rahim Nayyar, I would not have incorporated it here. For, however, reliable as a reporter he would still have been the only witness of what was said, while my purpose here is to incorporate only such facts as have the most irrefutable evidence behind them. But as later events also proved that when Maulawi Muhammad Ali renewed his Bai‘at with Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), he was actuated only by fear and expediency, we have no reason to disbelieve the statement of Maulawi Abdur Rahim Nayyar. There is also another incident which goes to corroborate M. Abdur Rahim’s story. Soon after this meeting on a certain occasion when I was present with Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) a message came to him from Maulawi Muhammad Ali to the effect that the Maulawi Sahib had resolved to leave Qadian as he had been insulted and humiliated. This also supports the statement of M. Abdur Rahim Nayyar.

There are hundreds of eye-witnesses to these events. Among the people who took part in this meeting, there are now some who have joined Maulawi Muhammad Ali’s party and others who have entered my Bai‘at. But I have every hope that if asked to make a statement on solemn oath members of both parties will alike testify to the truth of the facts as I have described them. It is hardly possible for anybody to hide facts of such importance relating to a gathering of such magnitude.

Before proceeding further with the narrative of these events. I wish to make a brief digression in order to present to my reader a picture of the moral condition of these men. This will enable them to judge for themselves how far Maulawi Muhammad Ali and his friends have been sincere in their dealings. When Khwaja Kamaluddin returned home from England for the first time he delivered a lecture on the subject of the dissensions. In this lecture he made a reference to this renewal of Bai‘at but gave it a most strange colouring. He represented the whole incident as though Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) convinced of the spiritual perfection of these men had asked them to enter into a special Bai‘at with him. Anyone who reads the description I have given of the incident will be in a position to understand that a person who can depict a Bai‘at, entered into under circumstances of the whole incident as a Bai‘at of fealty or a mark of favour, and thus tries to throw dust into the eyes of others can ill deserve our esteem. The actual words used by Khwaja Sahib were, “He (Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra)) required from me a second Bai‘at.” This is quite true. But what kind of Bai‘at was it? Bai‘at-e-Irshad. Can you say honestly that he got me to renew my Bai‘at? It was indeed Bai‘at-e-Irshad and not a renewal of Bai‘at or Bai‘at-e-Taubah. After this there is yet another kind of Bai‘at and that, is Bai‘at-e-Dam. Now go and look up the books of Sufis to find out from what class of disciples they received Bai‘at-e-Irshad. They receive Bai‘at-e-Taubah when they accept a disciple into their following, and when they observe in him the capacity for strict obedience, they receive from him the Bai‘at-e-Irshad, and when they come to possess full confidence in him, they receive from him the Bai‘at-e-Dam. (Vide Andruni Ikhtilafat-e-Silsilah Ahmadiyya kei Asbab, p. 58)

But to resume, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) was annoyed at the action of these men and most seriously so. He made them renew their Bai‘at. But while other people had their hearts chastened by the experience, the incident served merely to fan the flames of hatred in the hearts of these men. The only difference the incident made in their conduct was that whereas formerly they sometimes exhibited their feeling in overt actions, after the incident they took care to conceal them, awaiting the psychological moment when this volcano of hate might be allowed to burst and demolish the edifice of Ahmadiyyat. From this time on, Maulawi Muhammad Ali fell into the hands of the other party who held beliefs different from those of the Community and his dissatisfaction gradually drove him so close to the other party that in course of two or three years by a process of imperceptible change, he came to identify himself wholly with their beliefs.

On the other hand, Khwaja Kamaluddin was a man who guided himself by the signs of the hour. He adopted a policy of avoidance in public of all discussions regarding the Khilafat and wished to see the question dropped for the time being. He did so lest the Community should become alert and impervious to any future intrigue. He fully realised that if full light were thrown upon the subject at that time, there would remain no loophole for any further tampering with the question. With this idea he began to render full outward obeisance to the Khalifa, but in the affairs of the Sadr Anjuman adopted a new policy. Whenever occasion now arose for carrying out commands by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) the records of the Anjuman began to use a new technique. It was not entered as command by the Khalifa but merely as a recommendation by the President accepted by the members. What was intended by this course of action was that the records of the Anjuman might not prove that this body ever took orders from the Khalifa. After the death of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra), there was an attempt on just these lines to mislead the Community, which, however, did not favour the attempt. It had therefore to be given up. It is in consequence of this record that these men now avoid any discussion of the question of Khilafat, fearing lest the people should have the memory of those days revived, and lest recollection of their past intrigues should make people doubt their present integrity.

In short, the policy they adopted was that while they complied with all the behests of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), they carefully avoided using the term Khalifa and used instead the term President. But God wanted to expose them. Accordingly it happened that Hakim Fadl Din Sahib, a very sincere Ahmadi and one of the oldest members of the Community made a will giving away his properties for the purpose of the propagation of Islam. The properties included a certain house which the Anjuman resolved to dispose of. The person from whom the house had been purchased by the testator applied to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) praying that the house might be sold to him at a price less than what it might command in the open market; and this in consideration of the fact that the house formerly belonged to him and he had to give it up for a very small price under the stress of certain difficulties. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) granted the prayer and wrote to the Anjuman directing it to sell the house to the applicant at a reduced price. This gave these men an excellent opportunity. They declined to comply with the orders of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), and thought that when members of the Community would come to know that Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) had resolved to dispose of a property belonging to the Community at a price less than that which was being offered for it in the market they would side with the Anjuman. They discussed and argued the matter with Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) and suggested that the applicant might purchase the house at a public sale, and that there was no reason why the Anjuman should incur the loss. In vain, did Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) explain to them that the applicant had sold the house for a small price under stress of difficulties and, therefore, deserved consideration. They, however, remained obdurate. At length, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) wrote to them out of displeasure that they might do what they liked; he would have nothing more to say in the matter. When the matter came up before the Anjuman, I was present at the meeting. Dr. Muhammad Husain, Secretary Anjuman Isha‘at-e-Islam, Lahore, mentioned the matter to me saying that as trustees of the Community we were responsible to God. He inquired from me what the proper course was for us to follow. I replied that as Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) desired us to make some concession, it was our duty to do so. Upon this, the Doctor Sahib said that Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) had granted us permission to do as we liked. But when the letter was read, I was able to perceive in it signs of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih’s (ra) displeasure. I, therefore, pointed out to the members that the letter was an expression of displeasure and not a permission. Therefore, I said, I still adhered to my previous opinion. Upon this, the Doctor Sahib made a long-speech in which he sought to impress upon me the need of the fear of God and of true piety. I, however, was still of the opinion that the course suggested by me was the right one under the circumstances, and that they were free to decide as they thought best. At that time, the majority of the members present supported their view of the case—in fact I stood alone—and the resolution was passed accordingly. When the matter came to the knowledge of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), he summoned them and asked for an explanation. They replied that the decision had been reached by common consent and mentioned me by name among those who were present at the meeting. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) then sent for me. When I went to him the other members were already with him. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) exclaimed, “Well Miyań, how comes it that my explicit commands are thus openly disregarded?” I said, “I have not disobeyed any commands.” He said, “In this matter I had given certain orders, then how was it that you acted against them?” I replied, “The members present here will bear witness that I gave them explicitly to understand that in this matter you did not approve of the decision proposed by them and that they ought not to persist in it, and that your letter signified not permission but displeasure.” Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), thereupon, turned to those members and remarked, “Mark! you call him a stripling, yet a stripling understood the purport of my letter and you did not.” He added many other words of admonition to the effect that virtue lay in obedience, and that they should change their ways or else they would be cut off from the blessings of God. Upon this these men expressed regret for their conduct but, nevertheless, from that day efforts began to be made to alienate the people from Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih. Charges began to be laid at his door, and in Lahore it began to be urged publicly that he should be deposed from his office by whatever means possible. These activities came to the notice of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra). The festival of Eid was close at hand. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) summoned them all from Lahore. (Khwaja Sahib was not present on this occasion. He had gone to Kashmir. Besides, as I have already said, he preferred to proceed by secret methods.) Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) had resolved to announce their expulsion from the Community in the course of the Eid sermon. Now, they knew full well that resistance was useless and that people would not lend ear to their words. They, therefore, for a second time sued for pardon and some of them had to renew their oath of Bai‘at. Thus was this danger averted for the time being. But still the experience did not bring about true repentance in their hearts. It served only to make them more guarded in their movements. It was at this time that Khwaja Sahib began his career of public lectures with a view to capturing the public mind. He delivered his lectures and himself wrote eulogistic reports about them for publication in the papers of the Movement. These reports were sent over the name of someone from among the audience. In this way he managed soon to build reputation for himself. Nor was his popularity to be wondered at. The teachings of the Promised Messiah (as) on which he drew were intrinsically attractive. Khwaja Sahib possessed natural capacity for eloquence, and was also a past master in the art of self-advertisement. He had a series of articles published in his own praise. Some were written by himself and some by his friends. The demand for his lectures grew and wherever he went, he took the opportunity indirectly or—where possible—directly to speak to Ahmadis regarding the relations between the Khalifa and the Anjuman. The reputation which he had acquired as a lecturer served to leave some impression behind.

It is a well established truth that when a person takes one false step, circumstances oblige him to take another. With the scope of his lectures widened, Khwaja Sahib had more and more occasion to come into contact with non-Ahmadis. He was unfamiliar with the inwardness of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and now a new difficulty confronted him. It often happened that a lecture of his was preceded or followed one of the five daily prayers. Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis had to offer prayers in separate congregations, and people naturally asked the reason for this separation. The situation was rather awkward for Khwaja Sahib. On the one hand he was not willing to forfeit his newly acquired popularity with non-Ahmadis, and, on the other hand, he was afraid of the displeasure of Ahmadis. In this strait he took recourse to various devices. On some occasions, he would say that the prohibition to pray behind non-Ahmadis was meant only for the common class of Ahmadis, in order to protect them from the influence of outsiders, that it was not intended for advanced Ahmadis like himself, and that he was prepared to offer his prayers behind non-Ahmadi Imams. On other occasions, he would say that he had to work under the orders of an Imam (Leader) and that the question should therefore he addressed to the Imam. Sometimes, he would say that if non-Ahmadis would revoke their fatwa of Kufr against the Promised Messiah (as), he was ready to offer his prayers behind them. Such and similar were the pleas he offered to excuse his failure to say his prayers behind non-Ahmadis. In fact Khwaja Sahib’s ideas had become poisoned already at the time of Dr. Abdul Hakim’s apostasy, and the poison began now to show its effects. Khwaja Sahib was a seeker of fame and popularity, and these restrictions were impediments in his way. He, therefore, resolved to do away with the restrictions at all cost. For this purpose, the first thing he did was to induce Dr. Mirza Ya‘qub Baig to write two articles in the Paisa Akhbar and the Watan to the effect that the prohibition against praying behind non-Ahmadis was only a temporary one. He thus tried tentatively to lay the foundation of a future movement in favour of a rescinding of the prohibition. But he had made a miscalculation. The articles brought home to some Ahmadis also were encouraged by this sign of weakness on the part of Ahmadis to charge them with narrow-mindedness and intolerance.

At this time, the question was put to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) whether differences between Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis related to essential matters of faith or to non-essentials. He replied that these differences related to essential matters. The reply created a great commotion. The non-Ahmadi papers made virulent attacks on Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) saying that he had magnified minor differences and had thus caused a split among Muslims.

Side by side with this controversy which raged between Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis there now came up another question which formed the subject of a warm discussion among Ahmadis themselves. This question concerned the propagation of Ahmadiyyat. From the moment he started his public lectures—with the exception of the very first—Khwaja Sahib had abstained carefully from making any reference in his lectures to the Promised Messiah (as), forgetting that God had ordained obedience to the Promised Messiah (as) as the sole remedy for all spiritual ills. Khwaja Sahib would studiously avoid all mention of the Promised Messiah (as), even when reference to him was called for by the subject of his address. He fully realised that without following such a course he could acquire no popularity among non-Ahmadis. And, as the objection of non-Ahmadis was to the personal claims of the Holy Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, the policy adopted by Khwaja Sahib brought him large audiences. Often these swelled into thousands, all eager listeners to what he had to say. Also, as has already been pointed out, Khwaja Sahib took special steps in order to make his lectures popular. The result was that his lectures achieved immense popularity and began to be applauded highly even by non-Ahmadis. Invitations for his lectures, began to pour in from all sides. When Ahmadis saw this eagerness and interest on the part of non-Ahmadis, many of them failed to realise its proper significance. What was only Khwaja Sahib’s personal popularity began to be mistaken by them for the popularity of the Movement. Ahmadiyya Associations at various centres—either of their own accord or at the instance of Khwaja Sahib—began to arrange for special lectures by him. They did so under the impression that by these lectures non-Ahmadis would be brought nearer to the Movement, and would ultimately enter its fold. The epidemic became so prevalent that other lecturers of the Movement also began to adopt the same policy. It seemed imminent that the trumpet which God had sounded through His Messenger was to cease to resound for ever. The time was one of extreme danger for the Movement. Some Ahmadi lecturers began to feel reluctant about making any reference to the Promised Messiah (as) in their lectures, and even when questioned on the subject, they tried to put it off by vague replies. This was not due to fear or hypocrisy, but the lecturers, following the example of Khwaja Sahib, had come to the honest conclusion that the adoption of his plan would prepare the way for the propagation of the Movement. There were of course some who used to mention the Promised Messiah (as) in their lectures, but even they made it a point never to mention him in connection with subjects which were likely to give umbrage to non-Ahmadis. This attitude was not, however, universal in the Community. There was a section of the Community which fully realised the significance of the policy adopted by Khwaja Kamaluddin. This section began to ply Khwaja Sahib with questions as to why he never made any reference to the Ahmadiyya Movement in his lectures. The reply of Khwaja Sahib was always disappointing and in this he showed his kinship with the apostate Dr. Abdul Hakim that the major subjects needed their first attention. When these had been settled, the minor subjects would settle themselves. “When people see us,” he said, “serving the cause of Islam, can they help admitting to themselves that we are in the right.” His was, he said, the work of a pioneer, clearing the forests and levelling the hillocks; when the road was prepared, the forest cleared and the land levelled, then would be the time for laying down the railways, cultivating the fields and planting the gardens. But why, he was asked, had God already put the world on trial by raising the Promised Messiah (as) if this pioneer work had still to be done? He was not expected—he was also told—to confine himself only and always to the subject of the claims of the Promised Messiah (as). Only this subject also should receive at least proportionate attention in his lectures. The only response Khwaja Sahib made to these queries and suggestions was that he did not stand in anybody’s way that while he was engaged in clearing the road others might go and lecture on other matters. At length on March 27, 1910 the situation compelled me to deliver an address and to point out to the Community the error of that policy. The result was that, with the grace of God, a section of the Community came to recognise this mistake and to realise the danger of the situation. Still, my lecture was not able completely to check this tendency which continued to grow. To this in fact was added the vexed question of the Kufr of non-Ahmadis.

It was at the time of this crisis—when, on the one hand, a section of the Community had already started upon a wrong track, and, on the other, non-Ahmadis, taking advantage of the vacillation on the part of some Ahmadis, had started attacking the Movement—that I wrote an elaborate article on the subject of the Kufr of non-Ahmadis. The article after necessary corrections by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) was published in the Tashhidhul Adhhan in its issue of April 1911. (See also this book p. 126). Under the circumstances of the time, the article proved very effective and succeeded in completely re-orienting the Community. And God be thanked, for the whole Community, with the exception only of a few individual members, fully recognised the fact that had they continued under the influence of the charm that had been cast upon them, they were sure, sooner or later, to lose the truth which had so recently come to them. Many there were who openly expressed their thanks and gratitude. A new spirit and a new enthusiasm ran over the Community and all Ahmadis with the exception of an insignificant few prepared themselves anew to discharge their duty.

As it happened, Khwaja Sahib and his friends were the party responsible for the policy, which I had set out to guard against. The publication of my article therefore naturally gave them cause for anxiety. Khwaja Sahib accordingly wrote an article in which my article was interpreted in a manner contrary to its real purport and had it endorsed by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) on the representation—and this Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih himself told me—that he (Khwaja Sahib) was in entire accord with what I had said but still he thought it right to present the subject in a form which should avoid giving offence to people.

So far as I can see, this was the time when Maulawi Muhammad Ali’s attitude underwent a transformation. All his writings previous to this plainly show that he believed the Promised Messiah (as) to be a Nabi. But now the situation had been altered. Now, if Khwaja Sahib had been discomfited in the controversy over the question of the Kufr of non-Ahmadis, it would have proved too severe a blow to the hopes of Maulawi Muhammad Ali. For, by reason of the popularity which his lectures had brought to Khwaja Sahib, Maulawi Muhammad Ali had by this time been relegated to a second place in the estimation of the Community. The first place was now occupied by Khwaja Sahib. He had come to wield a more than ordinary influence in the Community, and people of the Jama‘at were ready to listen to him and to accept his lead. Maulawi Muhammad Ali and his friends now hoped to take advantage of this popularity in order to compass their own ends. This important factor, it would appear, effected a revolution in the attitude of Maulawi Muhammad Ali, and induced him openly to identify himself with the views of Khwaja Sahib. Thus the party became united both in its beliefs and its policy. Before this, Maulawi Muhammad Ali was himself opposed to the policy followed by Khwaja Sahib in his public lectures. This also appears from the fact that on the occasion of the Annual Conference of the Community held in March or December 1910, and in the course of a discussion on the need or otherwise of Ahmadiyya public meetings he opposed and attacked Khwaja Sahib. Thus, it was during the year 1910 or 1911, and under the circumstances which I have described above, that a change came over the outlook of Maulawi Muhammad Ali.

While efforts were being made by Khwaja Sahib to undermine the distinctive aims of the Movement—and if he could have had his way, he would not have hesitated to alienate the Jama‘at from its central purpose and to have it absorbed back into the general body of non-Ahmadis—the question of altering the organisation of the Jama‘at had not been forgotten by his party. Two lines of action were adopted to this end. The first was that, as already stated all the directions of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) to the Anjuman were treated and represented as though they were recommendations of the President, and the second was that Maulawi Muhammad Ali began to be bolstered up and treated as a virtual Khalifa. The object was that Maulawi Muhammad Ali should acquire influence with the Jama‘at as well as prominence among the people outside. Thus at the meetings of the Anjuman it began to be declared openly that whatever Maulawi Muhammad Ali should command would be carried out. On one occasion Shaikh Rahmatullah referring to Maulawi Muhammad Ali said in so many words, “He is our Amir.” It is also said that on the occasion of a Conference of Religions held in 1911, where Khwaja Kamaluddin and Maulawi Muhammad Ali went to read their papers, Khwaja Sahib in answer to inquiries made by people, described Maulawi Muhammad Ali as his pir, a spiritual chief or leader. This report of the incident has been current since the lifetime of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra). and has never been contradicted by Khwaja Sahib—so that it may be presumed to be true. Similarly on every possible occasion attempts were made to push Maulawi Muhammad Ali to the forefront so that the public eye should be diverted from Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) and directed towards Maulawi Muhammad Ali. Both plans, however proved futile. The failure of the first was brought about in this way. In 1910, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) wrote to the Sadr Anjuman, saying that as he held the office of Khalifa, he could neither be member nor president of the Anjuman, and that in his place Mirza Mahmood Ahmad (the present writer) should be elected president. Thus ended the first of the two plans. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) separated himself from the Anjuman and in his place I was appointed president. It could no longer be said that orders of the Khalifa were carried out not because he was Khalifa but because he was President of the Anjuman.

The other plan was defeated by Khwaja Sahib himself. As soon as he began to be popular he began to push his own personality to the front, and he was able to capture the attention of the people. Maulawi Muhammad Ali thus receded into the background, and his opinion no more carried the weight it formerly did.

Towards the end of 1910, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) fell from his horse, and for some days he remained in a very precarious condition. He told Mirza Ya‘qub Baig, his medical attendant at the time, that he was not afraid of death and that he wanted to know if his condition was really dangerous. For, in that case he would like to dictate some instructions. But these people feared it might be against their interest for Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) to leave any instructions. They, therefore, assured Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) that his condition was not so dangerous, and that if his condition became critical they would give him timely intimation of it. But as soon as they departed from the presence of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) they held a consultation. At noon, Dr. Mirza Ya‘qub Baig came to me and asked me to proceed to Maulawi Muhammad Ali’s house, as a consultation was to be held there. My maternal grand-father, Mir Nasir Nawab Sahib, had also been invited. When I reached there I found Maulawi Muhammad Ali, Khwaja Kamaluddin, Maulawi Sadruddin, and one or two others. Khwaja Sahib opened the conversation. He said, “We have called you because Maulawi Sahib (i.e. Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra)) is very ill and weak. As we cannot stay on here—it being necessary for us to return to Lahore—we have been obliged to trouble you at this time, so that we may come to some understanding to avert trouble. We can assure you that none of us aspires to be Khalifa. At least I can assure you that I entertain no such aspiration and a similar assurance will be given to you by Maulawi Muhammad Ali!” Here, Maulawi Muhammad Ali interposed and gave a similar assurance on his part. Khwaja Sahib then continued: “Nor do we find any body better fitted for the Khilafat than you, and this is our considered opinion. But we would request you to do one thing. You should not let the question of Khilafat be decided so long as we do not arrive from Lahore. We are afraid lest some hasty person should precipitate trouble. It is essential that our arrival from Lahore should be awaited.” To this Mir Sahib replied, “Yes, it is necessary that some understanding should be reached to prevent trouble.” I, however, realised the gravity of the situation, and remembered at once the practice of the Companions of the Holy Prophet (sas) who regarded it utterly improper in the lifetime of one Khalifa to discuss the selection of another, even if the selection were contingent upon the death of the living Khalifa. Accordingly, I replied that it was a sin to discuss the selection of a successor to Khilafat while a Khalifa yet lived, and to decide that on the death of a living Khalifa a specific person should be appointed to succeed him and that therefore I considered it a sin to speak on the subject.

Readers will note in this speech by Khwaja Sahib certain points, which are specially worthy of attention. Firstly, that only a few hours before, these people had assured Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) that his condition gave no cause for anxiety and that there was no necessity for making a will and yet no sooner had they left his presence than they began to think of his successor. Secondly, that the speech assumed that while they had no desire for the office of Khilafat, I did have such a desire. I did not, however, think it necessary to enter into any discussion, because an important question of principle was involved, and the safeguarding of that principle was more important than anything else.

As regards the disclaimer by Maulawi Muhammad Ali and Khwaja Kamaluddin of any desire on their part for the Khilafat, subsequent events prove that by such disclaimer they only meant that they had no desire for the title of Khalifa. For, it appears that in place of the old title of Khalifa, they have created the new title of President or Amir which in practice is the same thing as Khalifa. This title is now held by Maulawi Muhammad Ali, while Khwaja Kamaluddin subscribes himself as Khalifatul-Masih (ra), even though he does not fulfil a single requirement of that office. One might think that his friends in conferring upon him this title and he in accepting it, have been working out the secret design of God to expose to the world Khwaja Sahib’s deep desire for the office of Khalifa, for in the absence of the actual office he was content to accept the bare title of Khalifa.

Nor must it be forgotten that subsequent events have amply proved that the proposal made by Khwaja Sahib and his friends was intended merely as a blind. For, although it could not be clearly seen at that time it is quite plain now that all the time they looked upon me as a bidder for the Khilafat, and wanted by their assurances to allay any suspicions—so that when time came and they should be present on the spot, they could adopt a line of action best suited to their purpose. For, if they were really in favour of my becoming Khalifa, there was certainly no reason for apprehending any trouble in case the election of Khalifa took place before their arrival on the spot. If in their opinion I was really the fittest person for the Khilafat, how could my election to that office become an occasion for trouble?

It appears from the Holy Quran that circumstances often arise which serve to accelerate the course of spiritual maladies. The same happened in the case of these men. In February 1911, I had a dream. I saw a large palace one portion of which was being demolished. Near the edifice, there was a field in which thousands of men were engaged shaping bricks. I inquired what that palace was and who the men were and why they were demolishing it. One of the men replied that the palace was the Ahmadiyya Jama‘at and that they were dismantling a portion of it in order to discard some of the old bricks (God protect us) and to replace some of the sun-baked bricks by kiln-made bricks, and that the place was to be enlarged. One particular fact I noted was that all these men faced towards the east. The thought passed through my mind that all the brick-layers were angels, and that as we had failed to put forth the necessary amount of labour towards the progress of the Jama‘at, angels had taken up the work with the permission of God (The Badr, 23rd February 1911). Moved by this dream, I secured the permission of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) to found a new Society among whose objects were the spread of Ahmadiyyat, implicit obedience to Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra), frequent recitations of Tasbih and Tahmid (singing Glory and Praises of God) and Durud (Praying Blessings on the Holy Prophet (sas)), the study and teaching of the Holy Quran and the Hadith, the promotion of mutual love and trust, and the offering of the daily prayers in congregation. Anybody who desired to become a member of this Society was to offer Istikhara (prayer for guidance) on seven consecutive days before he enrolled as a member. No sooner was the foundation of the Society announced than there arose a storm of opposition, and it began to be asserted openly that it was a move to secure the Khilafat. God be praised that a considerable number of the members of the Society are now associated with the party of Maulawi Muhammad Ali and they are in a position to testify that the Society had nothing to do with the question of succession to the Khilafat. The Society was engaged solely in the work of propagation. This fact has already been formally admitted by some former members of the Society, who are now members of Maulawi Muhammad Ali’s party, namely, their lecturers Maulawi Muhammad Husain, alias Marham-e-‘Isa and Maulawi Faqirullah, Superintendent of the office of the Secretary, Anjuman Isha‘at Islam, Lahore. This Society came to secure nearly one hundred and seventy five members and, by the grace of God, it succeeded in removing the prevailing slackness and, in infusing new enthusiasm for the cause of propagation not only among its own members but also among the general body of the Community. Members who had slackened down were roused to activity, while those who were already active increased in their zeal. Curious about the Society Khwaja Sahib also wanted to become a member but the condition of seven day’s special prayers seem to have proved too much for him or perhaps something else stood in his way which at present I cannot recall.

As the object of this Society—the Ansarullah—was the propagation of the Ahmadiyya Movement, I think it relevant at this place to state that just as on the question of Khilafat I had not ventured to take any step until I received a suggestion on the subject from a vision, even so on the question of the best method of public preaching, I deferred coming to any decision until I had offered Istikhara on the subject and had been granted a sign from God. It happened in this way. When objections began to be raised by members of the Community to the method of propagation adopted by Khwaja Kamaluddin, I offered prayers of Istikhara. After those prayers, I had a vision, in which I was shown that Khwaja Sahib had mistaken dry bread for cake and was offering the same to the public. It was after this vision that I undertook to criticise the method of Khwaja Sahib, a subject on which I had previously maintained perfect silence.

As I have already stated, the Community at large had by this time come to realise fully the gravity of the situation, and was alive to the dangers of the road on which Khwaja Sahib was seeking to lead them.

The major portion of the Community was now prepared to resist every external or internal endeavour to divert them from the central purpose of the Movement. Nevertheless as Khwaja Sahib and his friends had adopted the policy of outwardly supporting the supremacy of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) and as they came frequently to pay their respect to him and to declare their loyalty, the Community at large failed to gauge the real state of their minds. A certain amount of regard, therefore, continued to be paid to them which, otherwise, they would surely have lost. The policy adopted by these gentlemen was to assure Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) that they recognised the supremacy of Khilafat. So on other questions also they took their cue from the known opinion of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih and studiedly echoed his words. This induced Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih to believe that they were loyal and sincere in their profession of faith, and let the veil of oblivion cover their past conduct. When anyone made any reference to their antecedents, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) was at times even displeased, and said that errors were common to men and it was wrong to recall their past, seeing that they were now what they ought to be. When, however, Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) breathed his last, the fact became evident that they had all along been acting with duplicity. For, now they made public their denial in a matter, in which Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra) used to testify to their affirmation and defend them against the critics who charged them with denial. Under the circumstances anything commendatory said about them by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih I (ra) cannot be put to their account, except as proof of their hypocrisy during the lifetime of Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih (ra). Or else, what they affirmed during his life-time they need not have denied after his death.