The next logical argument for the existence of God that I would like to present relates to the moral code inscribed in the fitrah [nature] of every man. In other words, just as the last argument related to the physical law that appears to be operating individually and collectively in human beings and other things in the universe, this argument is based on the moral code that is operating in the fitrah of all human beings and no wise person can deny this. The knowledge of good and evil is inscribed in the fitrah of man and no one is devoid of it. It is possible, indeed, that it may be weakened or suppressed almost to the point of extinction in someone as a result of external influences; even then it cannot but show up somehow, in one form or another, from time to time. Everyone, however wretched his condition may be, by nature, likes good and hates evil. An extremely callous, long-standing, and habitual thief, who has been burying his fitrah in the dark veils of sin with repeated acts of stealing and snatching other peoples’ belongings illegally, jaded by chiding from people or to protect himself from the probing of his own conscience, may shamelessly justify himself saying that his act of stealing is not a bad act because, like other people who undertake various professions to earn their livelihood, he too is working hard, toiling and risking his life to sustain his family. Despite all this, he certainly passes through times when his conscience reproaches him and tells him that his deeds are improper and malicious. That is why, many a time, when a thief grows old and realises that the end is nigh, he becomes inclined to give up thieving and starts paying attention to making amends with his conscience. Even if someone’s conscience is utterly muted, so much so that he starts taking pride in his misdeeds and apparently has lost the sense of good and evil completely, it will not be hidden from careful observers that in fact such a person is not devoid of the natural virtue called the sense of good and evil. In dealing with others he appears to have no conscience but when it comes to others dealing with him his suppressed conscience wakes up and he would never agree to give up the smallest of his rights, as determined by his sense of good and evil. For instance, take a long-standing and habitual thief who has annihilated his fitrah by repeated acts of stealing and may feel or appear to feel justified in that—but when someone else lays his hands on his belongings, his half-dead fitrah comes alive to stand guard over his rights. Similarly, an adulterer, who is always on the lookout to violate the chastity of the daughters, sisters, and wives of others, and indulges in his profane act so much that if someone attempts to stop him, he would shamelessly defend himself saying that there was nothing wrong with it, as he did so with the consent of the other party and that in any case others should mind their own business. But if someone else lays their hands on his own family, he goes mad with rage and he forgets that if he is entitled to fulfil his sensual desires, so are others. Likewise, a habitual liar may gain pleasure by deceiving others, but when someone else deceives him by lying, he becomes filled with rage and anger and seeks revenge.

In short, the knowledge of good and evil is inherent in everyone and that is a strong reason to believe that man did not come about by himself as a result of mere chance or a blind law, but an All-Knowing and Wise Being has created him with a specific purpose. The purpose is that he should nurture his natural instinct, implanted in him as a seed, to open avenues of great progress. This will develop the image of the perfect source of beauty and grace and the only fountainhead of life—i.e. God—in himself and enable him to go on achieving the heights of all kinds of beauty and grace throughout eternity. Think hard: This sense of good and evil inscribed in the fitrah of every man, and this hidden fountain of light that illuminates the heart of every human being, can never be the result of blind chance or mindless evolution. It clearly proves that the Creator of this natural instinct is a Conscious Being with a decretive will, who has created man for the purpose that he develop this natural instinct to merit higher rewards. I cannot imagine that anyone with an iota of the ability to reflect can call this inherent sense of good and evil, present in every human being, merely a result of chance or natural evolution. Some say that this universe is like a machine and its components work automatically in their respective spheres according to their purpose, thus concluding that there is no God. They should think honestly, can this inherent sense that makes everyone inclined to do good be the result of a blind mechanism? Is there, or can there be, a machine that can distinguish between the poor and the rich, the fortunate and the unfortunate, the young and the old, the frail and the strong and the orphan and the non-orphan? Take for instance a flour-grinding machine: will it grind better and faster for a person who is poor or unfortunate or old or frail or orphaned than for a rich or well-off or young and robust man, or a child with living parents? If there is no such machine, and there cannot be one, then does not the inherent sense of good and evil, and man’s natural liking for good and for a show of mercy, love, forgiveness, or helping the afflicted, or making a sacrifice under appropriate circumstances, prove that human life is not operating automatically like a machine, but that there is another Being who has inscribed these emotions in his fitrah with a particular purpose?

Similarly, it is part of human nature for man to view evil with abhorrence; and he feels remorse if he happens to commit evil while he is unmindful or provoked. This also proves that human life is not machine-like; rather, some Higher Being has created it with a particular purpose, and natural guards have been appointed over the citadel of his heart with a special purpose. A wealth of emotions is embedded in man’s heart and the knowledge of proper and improper use of each emotion is also sown in his nature and so is the tendency to opt for the proper use and shun its improper use under all circumstances. The law or Shariah is always revealed to nurture these hidden seeds in human fitrah.

In short, the knowledge of good and evil, which is inherent in human nature, is strong evidence that man did not come into existence by himself and his life is not machine-like; rather, in the background there is an intelligent Being with a determined will who has created him with a purpose.

If at this point someone asks the question, is it not possible that this sense, referred to as the innate sense, might be the result of surrounding circumstances, as well as family and national traditions—that is to say, this liking for good and aversion to evil may not be inherent, but that it was something humans learnt through experiencing what is good and bad and, after a long time, this became established in their minds and appears as if it is inherent—the answer to this is that although this criticism appears worthy of consideration, if we examine it carefully it becomes obvious that there are only two ways of acquiring the knowledge of good and evil: either by long-term experience and the effects of our surroundings, as the questioner thinks, or by bestowal from a Higher Being, as Islam teaches us—one cannot think of a third way. What we have to do now is see which of the two is correct and based on reality. The first thing we notice is that there is a kind of uniformity about this knowledge of good and evil, regardless of the people or the times; i.e. this understanding in its essence appears to be similar in its form and style among every people and during every age. This clearly proves that it could not be the result of experience and impact of our surroundings, but has been bestowed upon human nature by an external power which is supreme and above all. Anything that develops as a result of experience and environmental factors must vary from people to people and from time to time, especially in the earliest days when different peoples were unaware of one another and lacked social interaction, because every people’s experience and conditions differ from one another. So this sense should definitely have developed differently in various peoples. We observe that national customs and ways, which are certainly shaped by environmental circumstances, differ in various peoples. Thus, if the realisation of good and evil were based on the conditions and experience of people, it would have varied from people to people and from time to time. However, this is not the case; rather, this sense has always been seen in every age and among every people to be the same, meaning in the condition of uniformity. Take, for instance, two peoples with completely different circumstances, one cultured, educated, and civilised and the other primitive, ignorant, and uncivilised. Despite this degree of difference, as far as the mere realisation [of good and evil] is concerned, it will be one and the same, and the differences, if any, will be in matters relating to its subsequent development; i.e. it would appear to have developed in one particular form and direction in one people and in a different form and direction in the other. However, when they are viewed independently of later effects, in essence they would appear the same in their form and style. This proves that the realisation [of good and evil] in its essence is not brought about by circumstances and experience but is inherent and no man is deprived of it.

The second proof that the realisation of right and wrong is inherent rather than acquired is that it appears to be operating in certain matters wherein it cannot be attributed, by any wise person, to experience and surroundings. In other words, these matters are such that their benefit or loss cannot be ascertained by human experience in any way; any realisation about them can never be attributed to experience and circumstances but will undoubtedly be taken as originating from a Higher Being, who has wisely bestowed it upon every human being. For instance, we see that some form of respect for the dead body has been prevalent throughout the ages among all people. Obviously, by its very nature, this has nothing to do with experience and environment and cannot be attributed to anything except natural instinct. In short, the comprehension of good and evil, relating to matters that have never been experienced and seem to carry no material advantage, is clear evidence that such a sense of awareness is not a learned behaviour but is an inherent trait infused into human nature by a Higher Being.

The third proof that the sense of good and evil is inherent is that in certain instances it manifests itself in a manner that is against national traditions, thereby it cannot be attributed to the latter as the effect can never be at odds with the causative agent. There are many examples found in history where, for instance, over a long period a nation becomes hard-hearted due to certain circumstances and its members become inclined towards ruthlessness and rigidity; national traditions make every member hard-hearted, merciless, and heartless. Nevertheless, a careful study of their nature, psychology, and life history will reveal a feeling of mercy covered by the veil of this heartlessness and this will be seen manifested from time to time, one way or another. Similarly, there are instances when a nation has passed through circumstances which have nurtured the feelings of mercy, forgiveness, and tenderness to an extent that, for every member, national traditions have become synonymous with mercy. However, a careful study will reveal that everyone in that nation would feel that if reformation requires harshness and punishment while forgiveness and mercy is detrimental, then one should resort to harshness as the appropriate punishment rather than forgiveness and mercy. In short, at times this knowledge of good and evil is also found at odds with a nation’s condition and indigenous traditions, and this is so because that is the part of fitrah which may be suppressed by circumstances but can never die. That is why it is observed many a time that the family and national circumstances mould someone’s disposition into a kind of a new nature that can be called a ‘second nature’. Even then, fundamental nature, when stirred, erupts through the veils of the second nature like a pent up volcano.

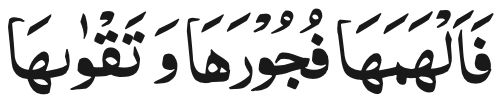

To summarise, indeed the circumstances and traditions lead to the development of a kind of nature, but that is a second nature and not the basic nature, or fitrah. The latter has nothing to do with national circumstances, traditions, or experiences but is part of human constitution. Fitrah, which has been bestowed with the knowledge of good and evil in an extremely judicious manner, is clear evidence that there is a rational Creator of this fitrah who has inscribed this element in it with a definite purpose. The Holy Quran says:

God has invested the fitrah of every man with the knowledge of good and evil and has told him through his fitrah that this is the good way and this is the evil way.

Again it says:

We showed man the two paths—good and evil (through his fitrah). Now, it is up to him to follow the way he likes.

Elsewhere it states clearly:

And remember the time when your Lord brought forth from the loins of the sons of Adam their offspring and made them witnesses against their own selves by saying, ‘Am I not your Lord?’ They replied, ‘Indeed, You are our Lord’. This He did lest you say on the Day of Resurrection, ‘We were unaware of the existence of our God’.

In short, the knowledge of good and evil exists in the fitrah of every man; this inherent knowledge substantiates that man did not come into being by himself nor is he the product of a blind law. This is such a clear proof of God’s existence that it cannot be denied by any reasonable person.

1 Surah ash-Shams, 91:9.

2 Surah al-Balad, 90:11.

3 Surah al-A‘raf, 7:173.