The third letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) was addressed to Maqauqis, the Governor of Egypt, who was the ruler of Egypt and Alexandria in subordination to the Caesar. In other words, he was a hereditary ruler, and like the Caesar, was a follower of the Christian religion. His personal name was Juraij bin Mīnā and he, along with his people, belonged to the Coptic nation. The Holy Prophet(sa) dispatched this letter in the hand of a Companion who took part in Badr named Ḥāṭib bin Abī Balta‘ah. The letter read as follows:

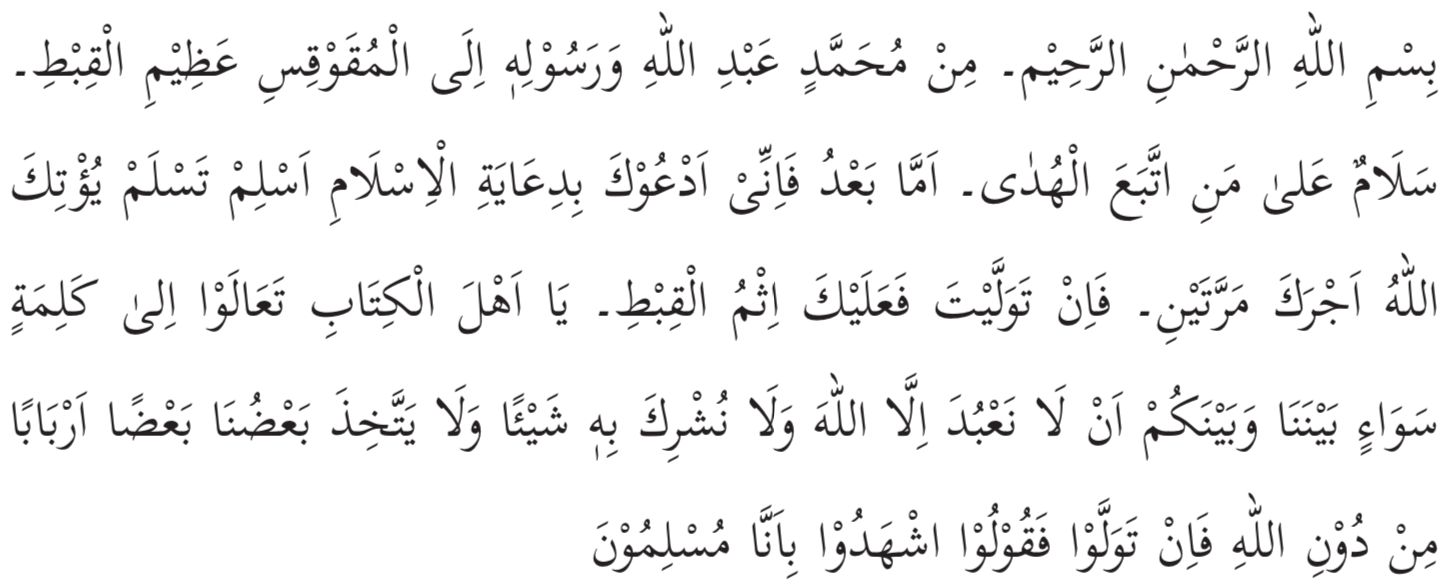

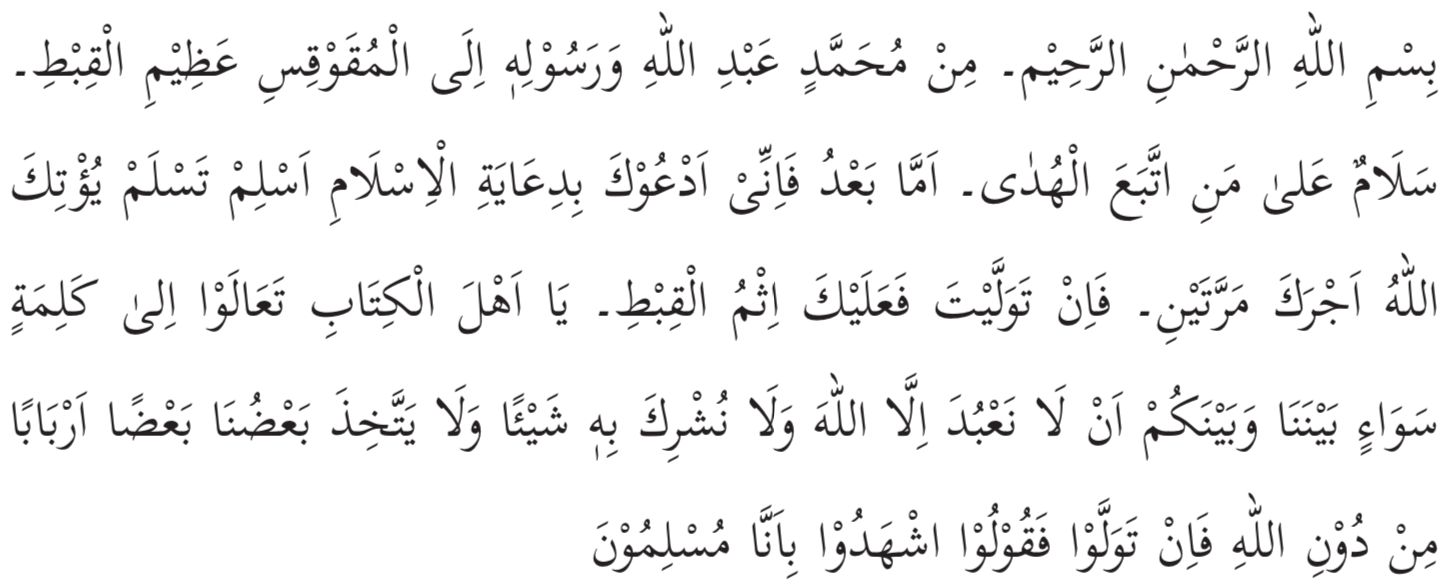

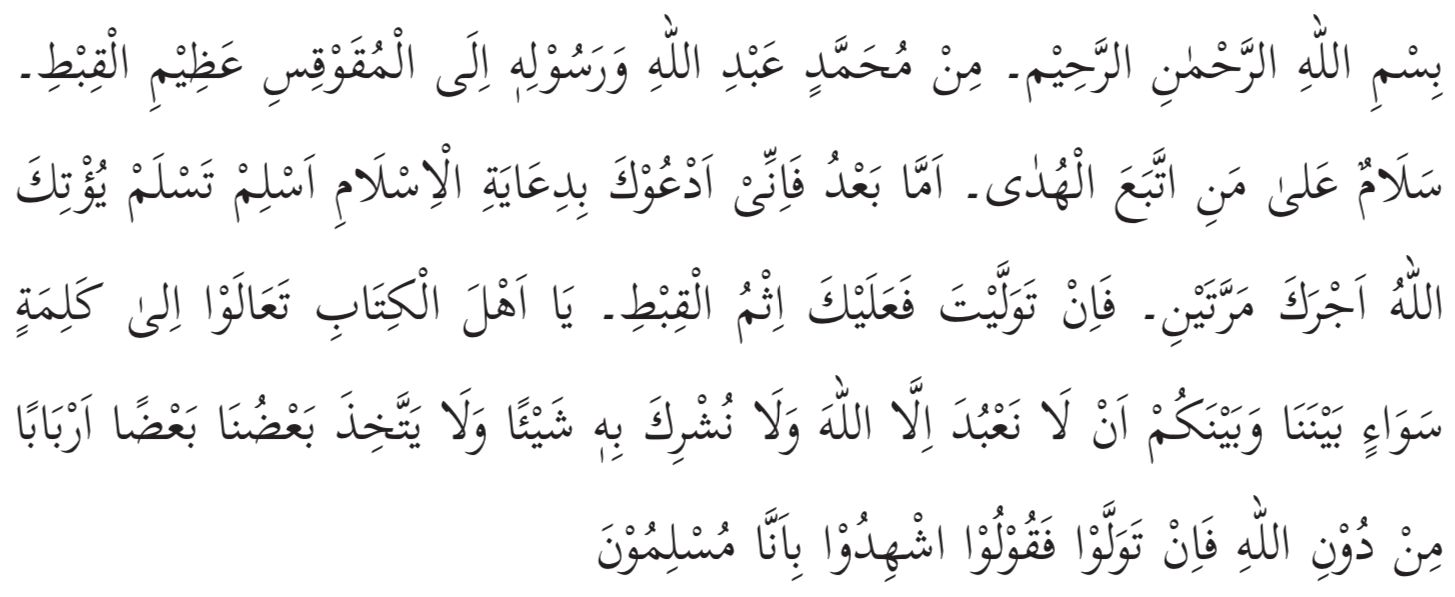

“I write this letter in the name of Allāh, Who is the Gracious, and who grants the best reward of one’s deeds. This letter is from Muḥammad, the servant of Allāh and His Messenger, to Maqauqis, Chief of the Copts. Peace be on him who follows the guidance. After this, O Ruler of Egypt! I invite you to the guidance of Islām. Embrace Islām and accept the peace of God, for this is the only way to salvation. Allāh the Exalted shall grant you a double reward. But if you reject this invitation, (in addition to yourself), the sin of the Copts shall be on your shoulders as well. O People of the Book! come to a word equal between us and you - that we worship none but Allāh; and that we associate no partner with Him in any case, and that some of us take not others as our Master and Lord. But if they turn away, then say, ‘Bear witness that we are followers of the One God and obedient to Him.”1

When Ḥāṭib bin Abī Balta‘ah(ra) reached Alexandria, he met with an attendant in the royal court, and after gaining access to Maqauqis, presented the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) to him. Maqauqis read the letter and in somewhat of a teasing tone, said, “If your master is actually a Prophet of God (instead of sending me this letter), why did he not supplicate to God that He should make me subservient to him?” Ḥāṭib responded, “If this objection is valid, then it falls upon Jesus(as) as well, because he did not supplicate against his opponents in this manner.” Then, by way of advice he said, “You should contemplate in a serious manner, because prior to this, in this very country of yours, there has been a person (i.e. the Pharaoh) who claimed that he was the Lord and Ruler of the entire world, but God seized him in such a manner that he became a lesson for all subsequent generations. I sincerely submit to you, therefore, that you should take a lesson from others, and not become one from whom others take a lesson.” Maqauqis said, “The fact is that we already have a religion, therefore, until we find a more superior one, we cannot leave our faith.” Ḥāṭib responded, “Islām is a religion which relieves a person from the need of all other faiths; however, it surely does not require you to relinquish your belief in the Messiah of Nazareth. As a matter of fact, it teaches belief in all the truthful Prophets of God. Just as Moses(as) gave glad tidings of the advent of Jesus, so too, Jesus(as) gave glad tidings of the advent of our Prophet, peace and blessings of Allāh be upon him.” At this, Maqauqis began to contemplate and took to silence. However, sometime thereafter, in another sitting when several high dignitaries of the church were present as well, Maqauqis inquired of Ḥāṭib, “I have heard that your Prophet was exiled from his homeland. Why did he not pray against those who drove him out, so that they would be destroyed?” Ḥāṭib responded, “Our Prophet was only forced into exile from his homeland, but your Messiah was actually apprehended by the Jews, who attempted to bring his life to an end on the cross; yet, he was unable to pray against his enemies and destroy them.” Maqauqis was very impressed and said, “You are undoubtedly a wise man, and have been sent as an emissary by a wise man.” After this, he said, “I have reflected upon what you have said about your Prophet, and have found that he has not taught anything evil, nor has he forbidden anything good.” Then he placed the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) in an ivory box, sealed it and handed it over to one of his responsible female servants.2

After this, Maqauqis summoned a scribe who was well-versed in Arabic, then he dictated the following letter addressed to the Holy Prophet(sa), and handed it over to Ḥāṭib. The text of the letter is as follows:

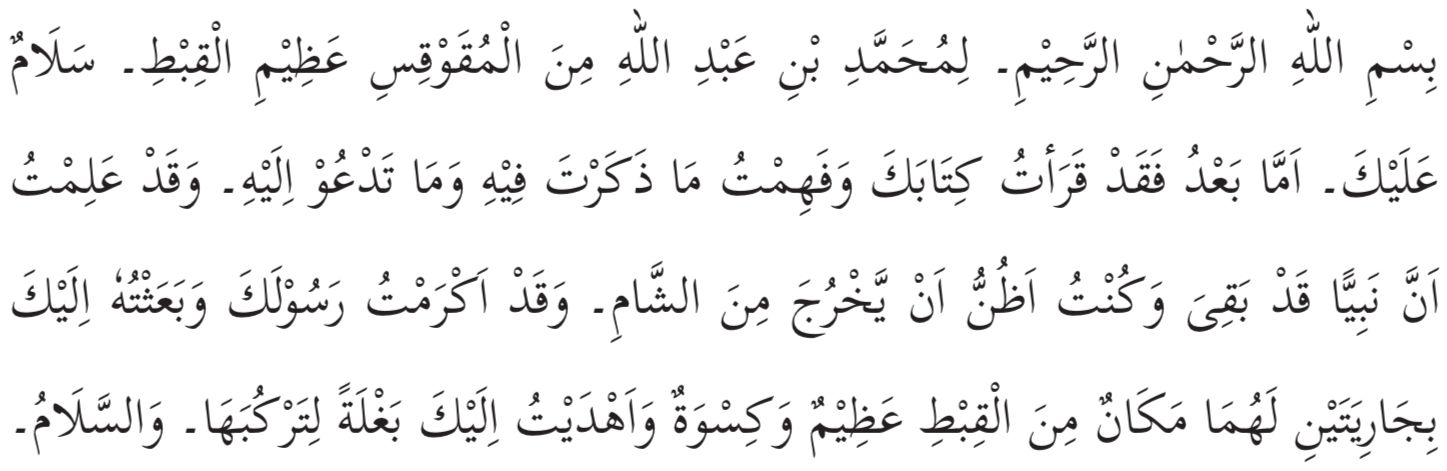

“In the name of Allāh, the Gracious, the Merciful. This letter is from Maqauqis, Chief of the Copts, to Muḥammad(sa), the son of ‘Abdullāh. Peace be upon you. I have read your letter, understood its contents, and pondered over your invitation. I knew that a Prophet was to appear, but I thought that he would be raised in the country of Syria (not in Arabia). I have treated your emissary with honour, and send two girls, who are held in high esteem by the Copts. I also send you some garments and a mule so that you may ride upon it. Peace be upon you.”

This letter demonstrates that Maqauqis of Eygpt treated the emissary of the Holy Prophet(sa) with reverence, and to some extent, he took an interest in the invitation of the Holy Prophet(sa) as well. However, in any case, he did not accept Islām. It is ascertained by other narrations that he passed away as a follower of the Christian faith.3 By the manner of his speech, it seems that although he took an interest in religious matters, he did not possess the serious nature that was required in this respect. For this reason, apparently, even though he acted respectfully, he dismissed the invitation of the Holy Prophet(sa).

The two girls sent by Maqauqis were named Māriyyah and Sīrīn and they were both sisters. As Maqauqis stated in his letter, they were both from the Coptic nation, which was the same nation to which Maqauqis belonged. These girls were not ordinary people, rather, according to the letter of Maqauqis, they were, “held in high esteem by the Copts.” In actuality, it seems that an ancient practice among the Egyptians was that they would present girls who belonged to their own families or were nobles of the nation to such revered guests with whom they desired to foster stronger ties. As such, when Abraham(as) went to Egypt, the Chief of Egypt presented a noble girl (i.e., Hagar) to him as well for marriage, who gave birth to Ishmael(as), and through him, became the mother of many other Arabian tribes.4 In any case, when the two girls sent by Maqauqis arrived in Madīnah, the Holy Prophet(sa) married Māriyyah, the Copt, himself, and gave her sister Sirin to the renowned poet, Ḥassān bin Thābit(ra) in marriage.5 Māriyyah is the same blessed lady who gave birth to Ḥaḍrat Ibrāhīm, the son of the Holy Prophet(sa),6 who was the only child born to him during his era of prophethood. It is also worthy of mention that due to the preaching of Ḥāṭib bin Abī Balta‘ah, both these girls had become Muslim even before reaching Madīnah.7 The mule which was sent to the Holy Prophet(sa) on this occasion as a gift was white in colour. It was named Duldul. The Holy Prophet(sa) would often ride on it and in the Battle of Ḥunain, the very same mule was used by the Holy Prophet(sa).8

The question as to whether Ḥaḍrat Māriyyah was kept by the Holy Prophet(sa) as a wife or a slave-girl is a matter of disagreement, the details of which we need not delve into here. In any case, there are two points which are definite. Firstly, that the Holy Prophet(sa) instructed Ḥaḍrat Māriyyah to observe Pardah from the very beginning,9 and with regards to this injunction it is established that this was only observed by free women and wives. As such, there is a narration that after the Ghazwah of Khaibar, when the Holy Prophet(sa) married Ṣafiyyah, the daughter of a Jewish Chieftain, the Companions fell into a disagreement as to whether she was a wife of the Holy Prophet(sa) or merely a slave-girl. However, when the Holy Prophet(sa) advised her to observe Pardah, the Companions understood that she was a wife, not a slave-girl.10 The second point to note is that history proves that the Holy Prophet(sa) never kept a slave for himself, rather, he would release any slave that came into his possession, whether female or male.11 In this respect as well, it is unimaginable and unacceptable that the Holy Prophet(sa) would have kept Ḥaḍrat Māriyyah, the Copt as a slave-girl. Allāh knows best. If anyone desires to study a summary of the Islāmic teachings relevant to slave-girls he may do so by referring to Volume 2 of this book.

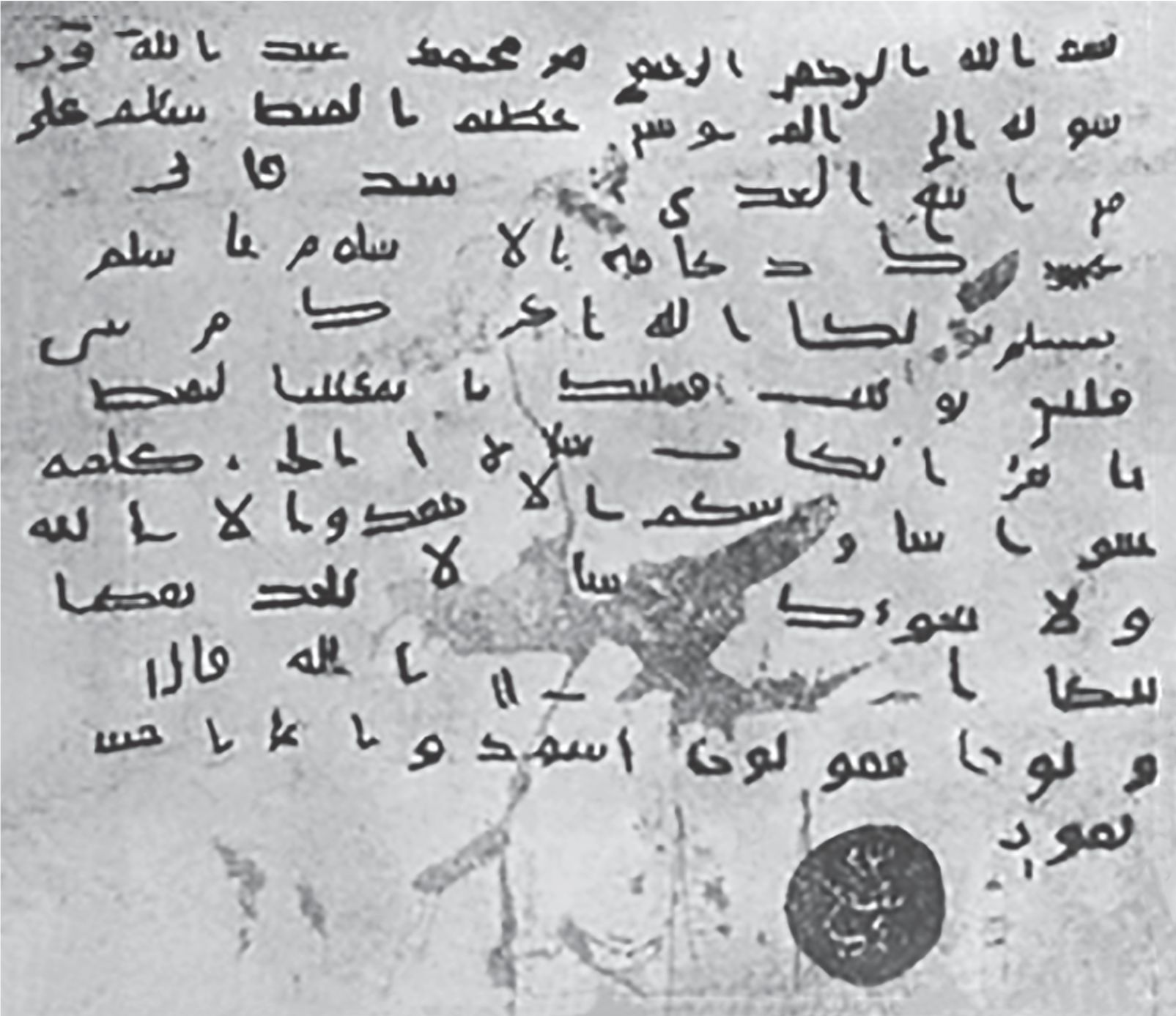

Another point to note in particular with regards to the letter of Maqauqis as well is that it remained hidden for many hundreds of years. The original document was discovered approximately 100 years ago, and we are receiving the honour of presenting a copy of this blessed letter here, i.e., a photo image. Although the writing style has changed significantly, most of the words on this image can be discerned if studied closely, and they are exactly the same words we have recorded above with reference to Islāmic books. In 1858 this letter was discovered by a few French travelers in a monastery in Egypt. The original letter is now present in Constantinople and its photographic image has been published as well.12 The individual who discovered this letter was Monsieur Etienne Barthelemy and its photographic image was perhaps first published in a renowned periodical by the name of Al-Hilāl in November 1904. After this, Professor Marlogious published a photo of it in his book ‘Muḥammad and the Rise of Islām.’13 It has also been published in a new book entitled ‘Tārīkhul-Islām As-Siyāsī,’ written by Dr. Ḥasan bin Ibrāhīm, Professor of Islāmic History at the University of Egypt.14 Many non-Muslim research scholars have confirmed that this is the original letter sent by the Holy Prophet(sa) to Maqauqis of Egypt.

On a side note, the discovery of this invitation, each and every word and letter of which is exactly the same as the narrations of Ḥadīth and Islāmic history, is a heavy proof of the great caution and magnificent honesty and integrity with which the reliable collectors of Ḥadīth and Islāmic historians have practiced in gathering these narrations. They transmitted a long chain of narrators verbally on the basis of their memory along with the actual text of the letter and stated that on a certain occasion the Holy Prophet(sa) wrote a letter to Maqauqis in the following words; and then after a vast period of 1300 years when the actual letter is discovered, it is proven in the likeness of broad daylight that the narration which Muslim Muḥaddithīn and historians relayed was accurate word for word. What greater evidence can there be in support of the authenticity of Islāmic narrations, and the honesty and integrity of the Muḥaddithīn? I do not suggest in the least that all narrators were reliable in every respect, because undoubtedly, in terms of memory, understanding and honesty, weak narrators can be found as well. As for those, however, who were reliable, they have no parallel in the history of the world.

1 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, pp. 27-28, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Al-Muwāhibul-Laduniyyatu Bil-Minaḥil-Muḥammadiyyah, By Aḥmad bin Muḥammad Al- Qusṭalānī, Volume 1, p 445, Al-Faṣlus-Sādisu Fī Umarā’ihi Wa Rusulihī Wa Kuttābihī Wa Kutubihī Ilā Ahlil-Islām..., Ḥadīth No. 4553

2 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, pp. 29-32, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 2, p. 37, Kitābun-Nabiyyi(sa) Ilā Kisrā, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

3 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 2, pp. 37-38, Kitābun-Nabiyyi(sa) Ilā Kisrā, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

4 Please refer to Sīrat Khātamun-Nabiyyīn(sa), Volume 1

5 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 4, pp. 460-461, Dhikru Sarārihi(sa), Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Usdul-Ghābah Fī Ma‘rifatiṣ-Ṣaḥābah, By ‘Izzuddīn Ibnul-Athīr Abul-Ḥasan ‘Alī bin Muḥammad, Volume 6, p. 264, Māriyatul-Qibṭiyyah, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon (2003)

Usdul-Ghābah Fī Ma‘rifatiṣ-Ṣaḥābah, By ‘Izzuddīn Ibnul-Athīr Abul-Ḥasan ‘Alī bin Muḥammad, Volume 6, p. 163, Sīrīn Ukhtu Māriyatul-Qibṭiyyah, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon (2003)

6 Usdul-Ghābah Fī Ma‘rifatiṣ-Ṣaḥābah, By ‘Izzuddīn Ibnul-Athīr Abul-Ḥasan ‘Alī bin Muḥammad, Volume 6, p. 264, Māriyatul-Qibṭiyyah, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon (2003)

7 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 4, p. 460, Dhikru Sarārihi(sa), Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

8 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 2, p. 186, Bighāluhū ‘Alaihis-Salām, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

9 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 4, pp. 460-461, Dhikru Sarārihi(sa), Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

10 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 470-471, Ghazwatu Khaibar, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

11 Please refer to Sīrat Khātamun-Nabiyyīn(sa), Volume 2

12 The Review of Religions (Qadian), July 1906 Edition, Volume V, No. 7, Page: Third Title

13 Mohammed And the Rise of Islām, By D.S. Margoliouth, p. 365, Chapter X (Steps Towards the Taking of Makkah), G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York and London, The Knickerbocker Press

14 Tarikhul-Islāmis-Siyasiyyi, By Hasan bin Ibrahim, Volume 1, Kitabur-Rasuli Ilal-Maquqas, p. 198