After the Treaty of Ḥudaibiyyah, the first letter to be sent out was perhaps to Heraclius, Caesar of Rome, inviting him to accept Islām. This letter was sent by the Holy Prophet(sa) immediately after the Treaty of Ḥudaibiyyah in the month of Dhul-Ḥijjah 6 A.H.1 The Holy Prophet(sa) appointed an intelligent and sincere companion to this service, named Diḥyah bin Khalīfatul-Kalbī, who had travelled to Syria before and was familiar with the territory. Diḥyah was a handsome young man, in whose personage, the Holy Prophet(sa) once saw Ḥaḍrat Gabriel(as) in a vision.2 Moreover, while sending this letter, the Holy Prophet(sa) expressed his wish that Diḥyah or whoever else performs this service, whether he apparently succeeds in this expedition or not, God-willing, would indeed enter paradise.3 After the preparation of this letter and after imprinting his seal, etc., the Holy Prophet(sa) instructed Diḥyah that take my letter to the Governor of Buṣrā4 (who was a vassal of the Caesar to the North of Arabia) and then reach Caesar through him.5 At that time, the Governor of Buṣrā was Ḥārith bin Abī Shamir who was the ruler and king of the Kingdom of Ghassān.6 By using the Governor of Buṣrā i.e., the country of Ghassān, as a channel, the Holy Prophet(sa) furnished proof of the same sagacity and wise planning as he had demonstrated before in the preparation of a ring. With regards to the courts of the Caesar and Chosroes, perhaps the Holy Prophet(sa) had heard that due to their worldly greatness and lofty stature, normally, they do not accept any letter directly, until it comes through the means of a Chieftain or Governor of a territory. As such, since the actual purpose of the Holy Prophet(sa) was to propagate the word of truth, he deemed it necessary to be mindful of these royal customs, so as to prevent hindrance in the actual work as a result. Furthermore, the intent of the Holy Prophet(sa) must have been that in this manner, in addition to the actual addressee, his message would also reach another Chieftain in the process as well. Moreover, as we shall see later, the same technique was employed when the Holy Prophet(sa) sent correspondence to the Chosroes of Persia. The Holy Prophet(sa) instructed his ambassador to take the letter to the Governor of Baḥrain and then to reach the Chosroes through him.7 On one hand, where this wise action on the part of the Holy Prophet(sa) substantiates his firm judgement, caution and wise planning, it also proves that to pay due respect to worldly rulers is not at odds with the grandeur of prophethood. It is for this reason that Allāh the Exalted states in the Holy Qur’ān that when We sent Moses and Hārūn to Pharaoh, We instructed them:

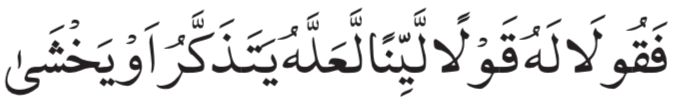

“Speak to Pharoah in gentle speech that he might possibly heed and take the path of the fear of Allāh.”8

The Holy Prophet(sa) was perhaps still preparing his letter addressed to Heraclius, when by Divine design, Heraclius himself became inclined to the commission of the Holy Prophet(sa). It is narrated in Bukhārī, most probably in the context of this incident, that as soon as the Ruler Heraclius reached Īlyā9, one morning he seemed worried and perturbed, upon which some of his religious courtiers inquired, “You seem to be in a bothered state today, what is the matter?” He said, “Last night, pondering over the stars (Heraclius was quite an expert in astronomy), I discovered the advent of a new King in a people who performed circumcision,” and he asked which nations perform circumcision in that day and age. His courtiers responded, “No one except the Jews perform circumcision, and you should not be worried of them. Issue forth an order to all the cities in your kingdom to begin killing the Jews.” However, the matter was still at this stage when Heraclius received news from the Governor of Ghassān that a man from Arabia named Muḥammad (peace and blessings of Allāh be upon him) has claimed prophethood and he is acquiring success in the land. Upon hearing this news, Heraclius immediately ordered that it be inquired as to whether the Arabs perform circumcision, upon which he was told that they do indeed perform circumcision. Heraclius spontaneously said, “Then it is he who is the King of this community.” As an additional act of caution he also wrote to a close acquaintance who was a great scholar in Rumiyyah and sought his counsel in this matter.10

However, during this time, the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) himself reached Heraclius. It seems appropriate that we write the narration in the words of Bukhārī at this place, because it is the most authentic and detailed narration available in this regard. Hence, ‘Abdullāh bin ‘Abbās who was the cousin of the Holy Prophet(sa) narrates:

“The Holy Prophet(sa) sent a letter to Caesar inviting him to Islām and sent this letter with Diḥyah Kalbī. The Holy Prophet(sa) instructed him to hand it over to the Governor of Buṣrā to forward it to Caesar. In this era, as a sign of gratitude for having defeated the Persian forces, the Ceasar of Rome travelled from Ḥimṣ to Īlyā by foot and it was in Īlyā (i.e. Jeruselum) that the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) reached Caesar. When Ceasar read this letter, he ordered that an individual from the people of this claimant to prophethood be sought out and presented before him. Ibni ‘Abbās relates that I found out from Abū Sufyān that in those days he had gone to Syria with some of his associates for the purpose of trade and this was the era after the Treaty of Ḥudaibiyyah. Abū Sufyān said, Ceasar’s men found us, took us to Īlyā and presented us before Ceasar. At the time, Ceasar was seated in his royal court with all his majesty wearing his crown and he was surrounded by the senior dignitaries of the Byzantine Empire. Caesar said to his translator to ask them who amongst them is closest in relation to this claimant of prophethood. Abū Sufyān said, I am closest in relation to Muḥammad(sa) and he is the son of my paternal uncle. Abū Sufyān relates that Ceasar called me closer to him and ordered my companions to stand before him, but to my back. Then he told his translator to tell my companions that I desire to ask various questions of him about the man who claims to be a prophet. Hence, if Abū Sufyān tells a lie, you are to point it out to me immediately. Abū Sufyān added, By Allāh, had it not been shameful to me that my companions label me a liar, I would indeed have lied at this occasion, but I was compelled to speak the truth. After this, Caesar began his questions by means of his translator:

Caesar: What sort of a family does this claimant belong to?

Abū Sufyān: He is of respectable lineage among us and belongs to a noble family.

Ceasar: Prior to this, has anyone else among you ever made a similar claim?

Abū Sufyān: No.

Ceasar: Prior to this claim, have you ever heard of this claimant being alleged to have told a lie?

Abū Sufyān: No.

Caesar: Was anyone among his ancestors a king?

Abū Sufyān: No.

Caesar: Do the noble accept this claimant or the weak and poor?

Abū Sufyān: The weak and poor.

Caesar: Are his followers increasing or decreasing?

Abū Sufyān: They are increasing.

Caesar: Has anyone left his faith being displeased with it?

Abū Sufyān: No.

Caesar: Does this man break his promises?

Abū Sufyān: No. But we are currently in a truce with him and we are afraid that he might betray us and I cannot say what might happen in the future. (Abū Sufyān says, other than this sentence, I could find no opportunity to say a word against the Holy Prophet(sa).)

Caesar: Have you ever had a war with him?

Abū Sufyān: Yes, there has been war.

Caesar: Then what has been the outcome of your battles with him?

Abū Sufyān: The outcome of our battles were like an ascending and descending bucket. Sometimes he was victorious and sometimes we.

Caesar: What does this claimant enjoin upon you?

Abū Sufyān: He tells us to believe in one God and refrain from polytheism. He stops us from the worship of our forefathers and orders us to observe prayer, give charity, refrain from evil, fulfil our promises and not to be dishonest in our trusts.

After these questions, Caesar said to his translator, say to Abū Sufyān, when I asked you about the lineage of this man you said that he was from a noble family and in fact, the messengers of Allāh are always raised from among noble families. Then I asked you if any one of you had made a similar claim before this, to which you responded in the negative. I asked you this because if anyone had made such a claim it could have been presumed that perhaps he was following a previous claim. Then I asked you whether he was alleged to have ever told a lie prior to his claim and you said no. From this I concluded, how could a man who has never told a lie in relation to people forge a lie against God. Then I asked you whether anyone amongst his forefathers was a king and you said no. I asked you this because if there was a king from among his forefathers, it could be presumed that perhaps he wishes to reacquire the lost kingship of his forefathers. Then I asked you whether the noble are accepting him or the weak and poor. To this you responded that the weak and poor are accepting him and the truth is that in the beginning, it is the weak and poor who accept the Messengers of God. Then I asked you whether his followers are growing or decreasing. You responded that they are increasing and this is the state of faith, in that it grows gradually until it is complete. Then I asked you whether anyone leaves his faith being displeased after having accepted it. You said no. For this is the state of true faith, once it enters the heart, (although one may leave it for another reason), nobody leaves it considering it to be abominable. Then I asked you whether this man breaks his promises and you said no. Such are the messengers of God; they never break their promises. Then I asked you whether there has been a war between you and him and you responded that yes, we have had war, and that sometimes he is victorious and sometimes we gain the upper hand. Verily, such are the Messengers of God; at times their people are put to trial, but the final victory is always theirs and triumph belongs to them. Then I asked you what he teaches you, and you said that he teaches us to believe in one God, refrain from polytheism, observe prayer, give alms, abstain from evil, fulfil our promises and not to be dishonest in our trusts. These are indeed the qualities of a prophet. After this Caesar said, I knew that a prophet was soon to be raised but O Ye Arabs! I did not believe he would be raised from among you. If what you have said is true, I believe the time is not far when this man would indeed, soon occupy the earth which is beneath my two feet at this time. If it is possible for me, I would travel to meet him; and if I were to reach him, I would find comfort in washing his feet. Abu Sufyān says that after this, Caesar asked for the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) and ordered for it to be read in the royal court. The following passage was written in this letter:

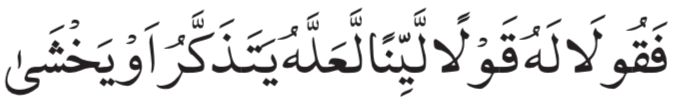

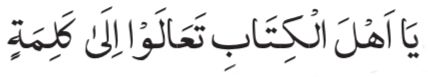

Translation: I write this letter in the name of Allāh, the Gracious, who grants the best reward of our deeds. This letter is from Muḥammad, the servant of Allāh and His Messenger, to Heraclius the King of Rome. Peace be on him who follows the guidance. After this, O King of Rome! I invite you to the guidance of Islām. Embrace Islām and accept the peace of God, for this is the only way to salvation. Embrace Islām and God the Exalted shall grant you a double reward. But if you reject this invitation, then remember, the sin of your subjects11 shall be on your shoulders. O People of the Book! come to a word equal between us and you - that we worship none but Allāh; and that we associate no partner with Him and that some of us take not others as our Master and Lord. But if they turn away, then say, ‘Bear witness that we are followers of the One God and obedient to Him.’

Abū Sufyān narrates that when this discussion and the reading out of the letter had been done, there was a great outcry by the Roman Governors, and there was so much noise that I could not understand what they were saying. At that time, we were ordered to leave the court. When I went out with my companions and found an opportunity to speak to them alone, I said to them, ‘The affair of Muḥammad(sa) has gained strength, for even the Emperor of Rome fears him. After this, I always felt myself to be low and insignificant. My heart was firm in the belief that Muḥammad(sa) would be victorious, until Allāh entered Islām into my heart, though I disliked it before.’12

A similar narration is also found in Bukhārī, in the chapter relating to the start of revelation. Ṭabarī, Ibni Isḥāq and the narrations of all the other historians with slight differences in wording, support this narration. Moreover, for a comprehensive account, Fatḥul-Bārī, Tārīkhul-Khamīs and Zarqānī are without equal.

At this occasion, due to the opposition of his high courtiers and particularly the religious leaders, although Heraclius remained silent, it seems as if the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) as well as subsequent and latter circumstances had made a deep impression upon his disposition. When he returned from Īlyā and went to Ḥimṣ again, during this time he had also received the letter from the scholar in Rumiyyah in which he had supported the opinion of Heraclius, in that it seems that a prophet is to be raised at this time. Upon this, Heraclius called upon the leaders of the Roman Empire once again and gathered them in his castle at Ḥimṣ. With the thought of secrecy, behind closed doors he addressed the Governors of Rome once more saying, “O Ye leaders of my empire, if you desire your own betterment and prosperity, and you wish to save yourselves from ruin and tread the path of success, and are desirous of saving your country from ruin, then it is my suggestion that you accept the prophet which has been raised in the land of Arabia.” Upon hearing this, the courtiers of Caesar began to lose control like a wild donkey, and tried to rush out of Caesar’s gathering. However, Caesar had the doors closed in his farsightedness. He immediately called these arrogant Governors and Bishops back again and lovingly said to them, “I was only testing your faith. Thank God you have proven to be steadfast.” When the courtiers of Caesar noticed this change in their King, they were gladdened, and in their happiness, fell before him in prostration. As such, this was the end to which Heraclius, the Emperor of Rome reached in this very weighty trial of his life.13

It should be remembered that when Heraclius read out the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) in his royal court at Īlyā, this was in actuality, a second reading. He had already read this letter in a private gathering prior to this.14 The details of this are that when Caesar received the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) for the first time, he summoned Diḥyah Kalbī in a private gathering and desired to read this letter amongst a few of his companions and intimates. At that time, perhaps this letter went to the nephew of Heraclius. Before presenting the letter to Heraclius, he opened the letter to read it himself. As soon as he saw the letter he exclaimed, “This letter is not acceptable in the least, because instead of writing your name first, the sender has written his own name,15 which is a disgrace to thy majesty. Similarly, instead of addressing you as the King of Rome he has addressed you as the King of Rome and this is a second disrespect.” But Heraclius silenced him saying, “What sense is there in that a letter comes to me from someone who claims to be a prophet and I throw it away without even reading it? And then, there is no harm in writing the word ‘King’ instead of ‘Emperor,’ for the actual Kingdom belongs to God alone and this claimant as well as I are the servants of God.” After this address he took the letter from the hand of his nephew and ordered that Diḥyah Kalbī be kept as a guest of the state prior to the public royal audience.16 In any case, however, there is no doubt that despite possessing many qualities such as wisdom and foresight, fear of the world, and greed for power and honour kept Heraclius deprived of guidance. It was as if the spark of guidance almost glittered in his heart, but was put out before it could shine forth.

However, despite this denial and loss, the honor of the Holy Prophet(sa) had found way into his heart. As such, history tells us that he safeguarded this letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) inviting him to Islām as a blessing,17 and it safely remained in his family for many hundreds of years. As such, there is a narration that when a few ambassadors of King Manṣūr Qalā’ūn (who was from 7th century A.H.) visited Al-Faranj, a golden box was called for and they were shown a letter wrapped in a silk cloth that a letter from your Messenger once came to a grandfather of mine named Heraclius. It is preserved in our home even today as a blessed gift.18 If anyone wishes to further study the history of King Manṣūr Qalā’ūn refer to the Encyclopaedia of Islām.19

Regarding the letter to Heraclius, there is also a narration that when Diḥyah Kalbī was to be presented before Caesar for the first time, it was said to him that as per the royal custom, upon coming before Caesar, one is expected to prostrate immediately and the head is not raised until he orders so himself. Diḥyah said, “I shall not prostrate before anyone except Allāh, whether I am permitted to go before him or not.” However, God’s grace was such that he found way to the Royal Court of Caesar, even without the observance of this un-Islāmic practice.20

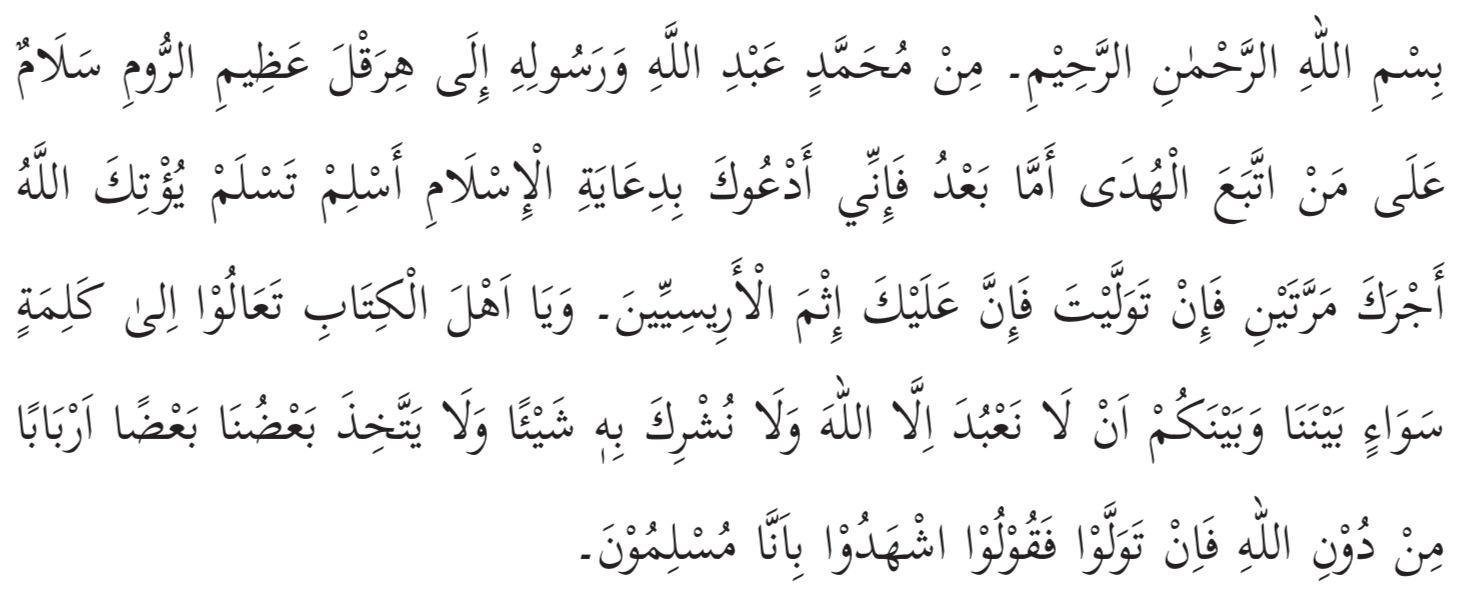

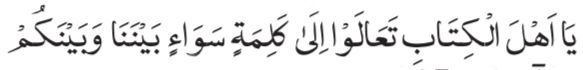

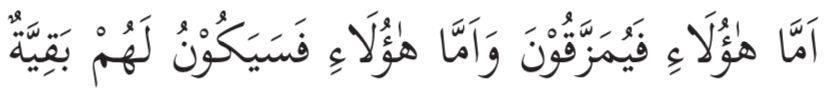

There is one aspect in the letter of the Holy Prophet(sa) addressed to Heraclius, upon the foundation of which Christian Historians have raised an allegation, and have also attempted to put the actual validity of this letter to doubt. The allegation is that the words:  which appear in this letter is a verse from among the first verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān. Moreover, narrations substantiate the fact that the first 80 verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were revealed in 9 A.H. when the delegation from Najrān came to visit the Holy Prophet(sa).21 Furthermore, since the letter addressed to Caesar was positively written immediately after the Treaty of Ḥudaibiyyah, therefore, verses revealed in 9 A.H. could not possibly be included in a letter written in 6 A.H. or 7 A.H. Hence, it is proven that this whole story of a letter is false altogether. This is the allegation which is raised at this instance. This allegation, however, is not a new one. This question was brought before Muslim historians and they have answered it with very elaborate explanations.22 In actuality, the fact is, and it so happened many times, that various phrases were spoken by the Holy Prophet(sa) or Ḥaḍrat ‘Umar(ra) and then a short time thereafter, identical verses of the Qur’ān were revealed. Moreover, it is not inconceivable for highly trained spiritual hearts to be influenced by the hidden rays of a Divine truth and express it by the special light of their heart or particular spiritual insight prior to its revelation. As such, numerous accounts of this are recorded in history and Ḥadīth, such as the conduct with the prisoners of Badr, funeral prayer of hypocrites, prohibition of alcohol, injunctions of Pardah,23 etc.24 Hence, it is not beyond belief that on this occasion, the Holy Prophet(sa) dictated this passage himself first and then the same passage was revealed in the form of a Quranic verse later on. Moreover, it is also possible that the first eighty verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were not all revealed in their entirety when the delegation of Najrān came to Madīnah. Instead, a verse or two had already been revealed, but since most were revealed then, it was said that the first eighty verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were revealed when the delegation from Najrān came to Madīnah. Then, it is also possible that this verse was revealed twice: initially in the first years after the migration; and secondly, in 9 A.H., etc.

which appear in this letter is a verse from among the first verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān. Moreover, narrations substantiate the fact that the first 80 verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were revealed in 9 A.H. when the delegation from Najrān came to visit the Holy Prophet(sa).21 Furthermore, since the letter addressed to Caesar was positively written immediately after the Treaty of Ḥudaibiyyah, therefore, verses revealed in 9 A.H. could not possibly be included in a letter written in 6 A.H. or 7 A.H. Hence, it is proven that this whole story of a letter is false altogether. This is the allegation which is raised at this instance. This allegation, however, is not a new one. This question was brought before Muslim historians and they have answered it with very elaborate explanations.22 In actuality, the fact is, and it so happened many times, that various phrases were spoken by the Holy Prophet(sa) or Ḥaḍrat ‘Umar(ra) and then a short time thereafter, identical verses of the Qur’ān were revealed. Moreover, it is not inconceivable for highly trained spiritual hearts to be influenced by the hidden rays of a Divine truth and express it by the special light of their heart or particular spiritual insight prior to its revelation. As such, numerous accounts of this are recorded in history and Ḥadīth, such as the conduct with the prisoners of Badr, funeral prayer of hypocrites, prohibition of alcohol, injunctions of Pardah,23 etc.24 Hence, it is not beyond belief that on this occasion, the Holy Prophet(sa) dictated this passage himself first and then the same passage was revealed in the form of a Quranic verse later on. Moreover, it is also possible that the first eighty verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were not all revealed in their entirety when the delegation of Najrān came to Madīnah. Instead, a verse or two had already been revealed, but since most were revealed then, it was said that the first eighty verses of Sūrah Āl-e-‘Imrān were revealed when the delegation from Najrān came to Madīnah. Then, it is also possible that this verse was revealed twice: initially in the first years after the migration; and secondly, in 9 A.H., etc.

However, perhaps the most solid evidence is furnished by the discovery of that letter which the Holy Prophet(sa) sent to Maqauqis of Egypt in the same era. This letter has been discovered in its original form and a photo of it shall be provided ahead. In this letter as well, the Holy Prophet(sa) has dictated the same passage, i.e.,  when it is categorically proven that this passage was also included in the letter to Maqauqis and the letter to Heraclius was also written in the same era, in any case, the issue of the validity of these letters cannot be doubted. This is my point of view.

when it is categorically proven that this passage was also included in the letter to Maqauqis and the letter to Heraclius was also written in the same era, in any case, the issue of the validity of these letters cannot be doubted. This is my point of view.

The letter inviting Heraclius to Islām which was sent by the Holy Prophet(sa) was a remarkably outstanding letter in terms of its meaning, the beauty of its wording and comprehensiveness. Although the letter itself is very brief, each and every word is like a gem, which has been placed into a magnificently crafted set of jewellery by a master jeweller. In this very brief letter, a wonderful model for preaching in general, and preaching to a Christian in particular has been presented. Furthermore, a complete lesson of the Unity of God has also been presented, the like of which cannot be found anywhere else. Then, the style of expression is so exquisite, as if two perfect streams of glad tiding and warning are flowing side by side. Moreover, a complete illustration of the truth of Islām has been presented without offending anyone or hiding behind the veil of diplomacy. Then, in the end the Holy Prophet(sa) also expressed his firm determination in that, whether you accept me or not, in any case, we are committed to the service of Islām.

Another weighty lesson which is learned from the account of the letter to Heraclius is that no grand truth can be accepted without a real spirit of sacrifice. It is evident from the questions that Heraclius inquired of Abū Sufyān, that he was a remarkably sensible and intelligent individual who had a deep study in the history of prophethood and religion. Furthermore, being influenced by the truth of Islām, the manner in which he gathered his courtiers in an attempt to convince them is not only proof of his wise thinking but also proof of his belief to an extent. However, the bitter fact is that he remained deprived of the blessing of faith and ultimately left this world fighting the armies of Islām.26 The reason for this is none other than the fact that his soul was not prepared for the weighty sacrifice which is necessary for true belief. Surrounded in the crowd of his courtiers, he desired to take a step towards Islām without losing his greatness and grandeur. To some extent he was a seeker of religion, but he was not prepared to leave the world, and this very weakness became the cause of his downfall. Undoubtedly, Abū Bakr(ra) and ‘Umar(ra) also acquired the finest inheritance of the world’s comforts and dignities, but they did not wish to bargain with Islām. They came to Islām empty handed merely for the sake of religion and then God who does not remain indebted to anyone, granted them such a kingdom, before which the collective kingdoms of Caesar and Chosroes were humbled. Caesar, however, was fearful of taking a step towards Islām empty handed. He extended his weak hand towards Islām and kept his strong hand firm upon the staff of his sovereignty. The outcome was that his divided heart could not acquire religion, nor could worldly power remain in his hands for too long thereafter. The heart of the Holy Prophet(sa) however, was a very sagacious one, and he was not one to forget even the smallest virtue of an individual. As such, there is a narration that when the Holy Prophet(sa) received news that Chosroes had torn his letter and thrown it away, but Caesar, apparently acted with dignity and respect, though he did not accept the invitation, the Holy Prophet(sa) said:

“The Persian Kingdom shall be destroyed at once, but God shall grant some respite to the Roman Empire.”27

Thus, precisely did it happen that the Kingdom of Persia fell to dust in only a few years, while the Kingdom of Rome, despite much of it being taken, remained in and around Constantinople for hundreds of years.28 So take a lesson, O ye who have eyes!

1 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 5, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

2 Shamā’ilun-Nabī(sa), By Muḥammad bin ‘Īsā bin Saurah, p. 8, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fī Khalqi Rasūlillāhi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 12, Nur Foundation, Third Edition (2010)

Musnad, By Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥanbal, Volume 2, p. 473, Musnadu ‘Abdillāh-ibnil-Khaṭṭāb, Ḥadīth No. 5857, ‘Ālamul-Kutub, Beirut (1998)

3 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 4, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

4 This was a city in Northern Arabia to the south of Syria which is referred to as Bosra in English. This should not be mixed with the new city of Iraq called Basra.

5 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Jihādi Was-Siyar, Bābu Du‘ā’in-Nabiyyi(sa) Ilal-Islāmi Wan-Nubuwwati..., Ḥadīth No. 2940

6 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 5, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

7 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-‘Ilm, Bābu Mā Yudhkaru Fil-Munāwalati Wa Kitābu Ahlil-‘Ilmi Bil-‘Ilmi Ilal-Buldān, Ḥadīth No. 64

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Jihādi Was-Siyar, Bābu Da‘watil-Yahūdiyyi Wan-Naṣrāniyyi..., Ḥadīth No. 2939

8 Ṭā Hā (20:45)

9 Īlyāa is the old name for Jeruselum, and this word most probably came from the Hebrew language, because in Hebrew, the word ‘Ail’ refers to God. As such, the meaning of Īlyāa would be ‘the City of God,’ or in other words, ‘the Holy City,’ and this is the meaning of Jeruselum.

10 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābu Bad’il-Waḥyi, Bābu Kaifa Kāna Bad’ul-Waḥyi Ilā Rasūlillāhi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 7

11 The word  (of which the plural is

(of which the plural is  ) means ‘farmer’ or ‘peasant,’ but here, the meaning is ‘subjects’.

) means ‘farmer’ or ‘peasant,’ but here, the meaning is ‘subjects’.

12 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Jihādi Was-Siyar, Bābu Du‘ā’in-Nabiyyi(sa) Ilal-Islāmi Wan-Nubuwwati..., Ḥadīth No. 2941

13 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābu Bad’il-Waḥyi, Bābu Kaifa Kāna Bad’ul-Waḥyi Ilā Rasūlillāhi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 7

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 13, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

14 Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 8, p. 277, Kitābut-Tafsīr, Tafsīru Sūrati Āli ‘Imrān, Bābu Qul Yā Ahlal-Kitābi Ta‘ālau Ilā Kalimatin Sawā’in Bainanā..., Ḥadīth No. 4553

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 11, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

15 Perhaps in that era, it was a custom in the royal courts that when addressing a Ruler, instead of writing, “From so and so to so and so,” the words “To so and so, from so and so” were used. As we have seen however, the Holy Prophet(sa) wrote the words, “From Muḥammad, the Messenger of Allāh to Heraclius, King of Rome.”

16 Al-Muwāhibul-Laduniyyatu Bil-Minaḥil-Muḥammadiyyah, By Aḥmad bin Muḥammad Al- Qusṭalānī, Volume 1, p 442, Al-Faṣlus-Sādisu Fī Umarā’ihi Wa Rusulihī Wa Kuttābihī Wa Kutubihī Ilā Ahlil-Islām..., Ḥadīth No. 4553

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, pp. 12-13, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

17 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 17, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, pp. 12-13, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

18 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, pp. 18-19, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

19 The Encyclopaedia of Islām, Number 27, pp. 685-687

20 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 2, pp. 31-32, Irsālur-Rusula Ilal-Mulūki/Kitābun-Nabiyyi(sa) Ilā Qaiṣara, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

21 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 1, pp. 171-172, Wafdu Najrāna, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 11, p. 327, An-Nau‘us-Sādisu Fī Dhikri Ḥajjihī Wa ‘Umrihī(sa), Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996) [Publishers]

22 Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 1, pp. 53- 54, Kitābu Bad’il-Waḥyi, Chapter No. 6, Ḥadīth No. 7

Tafsīrul-Qur’ānil-‘Aẓīm (Tafsīru Ibni Kathīr), By ‘Imāduddīn Abul-Fidā’ Ismā‘īl bin ‘Umar Ibni Kathīr, Volume 2, pp. 47-48, Tafsīru Sūrati Āl-e-‘Imrān, Under verse 64, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon (1998)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 11, p. 327, An-Nau‘us-Sādisu Fī Dhikri Ḥajjihī Wa ‘Umrihī(sa), Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

23 Islāmic injunction of veiling [Publishers]

24 Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 1, p. 665, Kitābuṣ-Ṣalāti, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fil-Qiblati..., Ḥadīth No. 402

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 2, pp. 322-323, Bābu Ghazwati Badril-Kubrā, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

25 O Allāh, invoke blessings and salutations on the Holy Prophet and his followers. (Publishers)

26 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 17, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

27 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 5, p. 17, Wa Ammā Mukātabatuhū ‘Alaihiṣ-Ṣalātu Was-Salāmu Ilal-Mulūki Wa Ghairihim, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

28 The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline and Fall, by Sir William Muir