Many Islāmic injunctions relevant to marriage and divorce, etc., were also revealed during this very year. At this instance, therefore, it seems appropriate to present a brief outline relevant to issues of marriage and divorce as taught by the Islāmic law. Firstly and foremost, it should be known that prior to Islām there was no specific law imposed among the Arabs with relation to marriage and divorce. In fact, the only form which existed was that of tradition and custom, and adherence to this depended on the will of every individual. It is for this reason that in different parts of the country and within various tribes, this custom took on differing forms.

On a general note it should be understood that there was no real limitation among the Arabs as far as lawful and unlawful relations were concerned, to the extent that people would even marry their step-mothers.1 The custom of forcefully taking possession of the widow of a near relative was also prevalent.2 There were different forms of marriage, and among them, four were most prevalent and renowned. Firstly, was the custom of marriage, which was established in Islām, albeit, in a more pure and wholesome manner. However, the remaining three were so filthy and vile that a person’s disposition feels hesitation in even alluding to them.3 There was no limit in polygamy, rather, the number of wives depended on a person’s individual requirement, wealth and desire.4 There was no law in order to ensure equality and justice between wives, nor did any responsibility lie upon the husband in this respect. There were no stipulated rights of men upon women, or of women upon men, rather, everything was left upon the husband’s choice. There was no law of divorce. A husband would separate from his wife when and how he so willed. If the husband did not allow, there was no other route for a woman to seek a divorce. As a matter of fact, even after a divorce had been issued, cruel men would continue to control their divorcees, and would forbid them from marrying anyone else.5 There was no law regarding ‘Iddat either. Immediately after separation, a woman would be considered free to marry another person.6 In short, there was no law of marriage or divorce among the Arabs and everything was left at the mercy of a man’s will. Men generally treated their wives in a very cruel manner and there was no place from where a woman could seek justice. When Islām emerged, it created a whole new world and except for a difference in administrative roles, which is only natural, in principle, women and men were given equal rights.7 Furthermore, the protection and supervision of these rights was not left upon men, rather, it was placed in the hands of government. The government was entrusted with the obligation to prevent both husband and wife from infringing upon the rights of one another, and to protect the women especially, who are generally oppressed. On the other hand, by its spiritual and moral influence, Islām strongly urged men not only to treat their wives with justice and equity, but with compassion and kindness as well. In this respect, Islām lay such emphatic stress that certain companions began to feel as if Islām had given women a free hand in all respects.8

The fundamental principle in Islām with regards to marriage and divorce is that the matrimony of man and wife possesses the nature of a civil agreement.9 Although this agreement possesses far greater love, loyalty and sanctity than ordinary agreements10 but in extreme circumstances, it can be dissolved as well.11 It is this very dissolution, which is known as Ṭalāq, Khula‘ or Fasakh-e-Nikāḥ. An outline of the Islāmic law detailing the manner in which this civil agreement may be established and dissolved shall be presented below.

Firstly, we take up the law of marriage:

In Islām, marriage is compulsory upon every Muslim who is able to do so and monasticism has been forbidden.12

The purposes of marriage have already been discussed previously, under the discussion relevant to polygamy. Repetition is not required here.13

Islām has stated clearly and explicitly where a relation of marriage is forbidden. In all other relations, a bond of matrimony may be tied. There is no restriction of people or race. In principle, the relations which are forbidden in marriage to a man are as follows: father’s wife, mother, foster-mother, daughter, wife’s daughter, sister, foster-sister, mother’s sister, father’s sister, brother’s daughter, sister’s daughter, mother-in-law, daughter-in-law, every lady who is already married, and to be in a bond of matrimony with two sisters at the same time.14 This last injunction has been further elaborated upon in a Ḥadīth.15

Since marriage is an agreement between man and woman and they are the ones who are responsible for its fulfillment, it is therefore necessary for both parties to be at consent. In other words, this relationship should be established with the agreement of both parties and without their consent, this bond must not be tied.16

Despite the restriction of Pardah, Islām permits, rather, encourages that both man and woman cast a glance upon each other, so that physical appearance does not become a reason for dissatisfaction later on.17

In Islām, the announcement of Nikāḥ must be made in public and secret marriages are not permitted.18 It is for this very purpose of announcement that another obligation prescribed by Islām is that when husband and wife meet for the first time, on this happy occasion, the husband arranges for a feast. According to ones capacity, honourable guests and neighbours, etc. are invited. The term used to describe this feast is a Walīmah.19

If due to some wisdom, the Walī or guardian of a boy or girl wishes to marry his child to someone in a state of childhood, i.e., before he or she reaches an age of maturity this is permitted.20 On certain occasions, in exceptional circumstances under special wisdoms, the need for this may arise, and the door of legal permission should be left open in this respect. However, in such a case, along with the boy possessing a right, the girl is also at liberty to terminate a relationship of this nature by means of a judge when she reaches an age of maturity.21 In Islāmic terminology this right is referred to as Khiyārul-Bulūgh. However, one should remember that where we have written that in exceptional circumstances a match may be settled in an era of childhood, this only implies a bond of matrimony by announcement, and intimate relations of husband and wife are not inferred here; the reason being that in order for intimate relations to take place both must have reached an age of maturity.22

There is no doubt that in marriage, the right of consent lies with the actual parties being joined in matrimony, and without their agreement, a relationship cannot be settled. Furthermore, if due to special circumstances, a marriage is settled in childhood, and the parties do not approve after reaching an age of maturity, the bond shall be considered void. However, a young girl, especially an unmarried girl, naturally possesses a simple disposition and is innocent. Furthermore, she has relatively less experience in life and is not greatly acquainted with the factors that lay the foundation for a truly happy married life. In addition to this, a woman is more emotional by nature as well, due to which often times her faculty of critical reasoning becomes veiled. Hence, in order to prevent her from heading into the wrong direction and protecting her from being ensnared by sly and cunning men, Islām orders that when an unmarried girl is to be wed, her father, or if her father is not alive, then another close relative, should remain with her as a guardian, and a bond should not be settled without his advice.23 However, if a dispute arises between the girl and her guardian, the opinion of the girl shall be given precedence.24 However, in such a case, it shall be necessary to bring such a dispute into the notice of a judge, so that if a girl is being lured into a trap, she can be saved.25 Since a widow tends to be well-acquainted with the ups and downs of marital relations, she is free to make an independent decision and the consent of a guardian is not required in her case, though it is preferable.26 The teaching of ‘guardianship,’ which is more or less found in most religions, but has been established by Islām in the form of a specified and detailed law, is an immensely beneficial and blessed system. Through this system, countless frauds associated with the marriage of girls are eradicated completely; and evil and cunning men do not receive the opportunity to show naive girls a lush green garden of opportunity and then lure them into a snare of deception. In western countries where women have excessive freedom in the matter of marriage, examples of this nature occur quite often where manipulative men convince innocent girls to marry them without the agreement and knowledge of their guardians by luring them with flattering speech and physical affection. However, when such girls fall into their trap, the cloak of deceit begins to come off. Even carnal desires begin to fall cold and shortly thereafter the homes of such girls - which they stepped into considering it to be a paradise - begins to turn into hell. In the beginning, it starts with a lack of consideration, then disagreement, then altercation, and then, separation. Finally the matter ends with divorce. Furthermore, another quality of the aforementioned system of guardianship is that in this manner, marriages are not only based on emotions, rather, other aspects which are extremely important in marriage are also taken into consideration. For example, the moral and religious aspect, family status, financial status, cultural aspect, suitability of dispositions, age and health, etc. It is obvious that if youngsters are left alone without any kind of advice or support from their guardians, so that they may engage in marriage however they please, since emotions tend to overpower the thoughts of youngsters, and putting exceptions to one side, since these emotions are usually lustful in nature, it is very likely for other aspects to be disregarded. Practically, all standards become subject to temporary sentiments, which usually result in dangerous consequences. However, through the system of guardianship, this risk falls drastically, because along with the emotions of the girl, the guardian’s lamp of understanding and experience also plays its role. Hence, the system of guardianship is a very blessed system, which maintains the legitimate freedom of a woman and her right of choice on the one hand, but on the other hand, she is also saved from the ill consequences of falling into the snare of deception laid out by evil and cunning individuals, as well as from the ramifications of bidding farewell to sensible and experienced advice and being tossed away in a torrent of mere emotion.

In Islāmic marriage, the dowry is a necessary condition. In other words, according to his individual capacity, it is compulsory upon the husband to give his wife a certain amount, property or item by mutual agreement.27 This dowry is like a legal debt and is subject to the absolute ownership and control of the wife. Moreover, this dowry is in addition to the portion she receives as inheritance upon the demise of her husband. In other words, a woman receives monetary gain by three different means: firstly, through her parents by way of inheritance;28 secondly, through her husband by way of his inheritance;29 thirdly, through her own dowry. To crown it all off, a woman is not responsible for any domestic expenses.

According to his capacity, the husband is responsible for bearing the necessary expenses of his wife.30 This expense is in addition to the dowry, etc.

If the husband or wife desire to settle a specific agreement or conditions at the time of their marriage, they are permitted to do so, and both shall be required to comply accordingly.31 However, they must not stipulate any conditions, which are against a commandment of the Sharī‘at,32 nor can they lay down a condition which is morally objectionable, or infringes upon the rights of a third party.33 According to this principle, if a lady is unable to live with another wife, it is permissible in Islām for her to stipulate at the time of her marriage that her husband shall not take a second wife. In other words, either the husband shall not marry a second wife, or he shall divorce the first before marrying again. Furthermore, since Islām does not order polygamy, rather, only permits it in exceptional circumstances, and such a condition does not infringe upon the rights of a third person either, an agreement of this nature shall not be deemed unlawful.34

Except for the administrative difference that a husband is the leader of the domestic hierarchy, Islām has afforded equal rights to both men and women.35 Even in this domestic leadership, a husband is not completely unrestrained, rather, he has been ordered to treat his wife with love, good manners, kindness and forgiveness.36 In his capacity as the leader of the household, although he has the right to take disciplinary action, this should be reasonable and necessary.37 Good treatment of one’s wife has been so emphatically ordered that the Holy Prophet(sa) would often state:

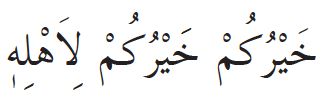

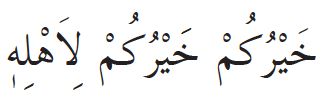

“O Muslims! The best person from among you is he who is best in the treatment of his wife.”38

The Holy Prophet(sa) would also state that a woman is like a rib bone, which is naturally curved and if a person attempts to bend it straight, it shall not be able to serve its purpose in the same manner as opposed to if it was left as is; furthermore, as a result, it shall break. In the same manner, a lady is also ‘curved’ in nature, i.e., her disposition possesses certain special charms, which apparently seems crooked at times, but they are actually the essence of her femininity. If anyone attempts to straighten this curved nature of a woman, he shall not be able to do so; instead, in the likeness of a rib bone, she will break.39 In other words, she will either be ruined, tossing and turning in agony like a fish out of water, or the matter shall escalate to separation or divorce. Hence, an individual should not undertake a useless effort to straighten the curved nature of a woman, which is part and parcel of her femininity. Instead, one should live harmoniously with her as she is. The Holy Prophet(sa) said:

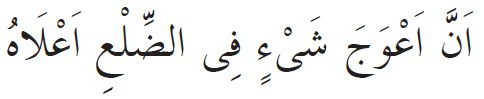

“The highest point of the ribcage is the most curved”40

In other words, this natural curve in the disposition of a woman is the distinct quality of her gender, and the greater the level of a woman’s femininity, the more curved her disposition shall be in nature. For this is the spirit of her unique nature. In this immensely wise instruction, the Holy Prophet(sa) has placed the mindset of men upon a perfectly correct and natural foundation with regards to their treatment of women. Moreover, the Holy Prophet(sa) has impressed upon the Muslims that if certain specific traits of a woman happen to cause an individual grief at times due to their incorrect application or expression, then undoubtedly, he should work to appropriately reform them, but should not become worried and strive to erase them completely. The reason being that they are part of a woman’s disposition and if they remain within their reasonable limits, it is these very characteristics that will become the foundation of one’s domestic harmony.

It is the obligation of a wife to obey her husband in all just matters and live together with emotions of love, gratitude and loyalty. She should protect his wealth and honour, train the children, and tend to his domestic affairs.41

Since the rights of a woman upon her husband, and a husband upon his wife possess a legal nature in Islām, for this reason, their mutual disputes may be presented in court.42 As such, it is ascertained from the Aḥādīth that Muslim women would bring complaints regarding their husbands to the Holy Prophet(sa), and he would issue verdicts in their favour,43 give them their rights and show kindness towards them in every possible way. This was to such an extent that due to their rights and the protective treatment shown to them, the Companions began to feel as if Islām had given women complete independence.44

Since a detailed discussion with regards to polygamy and other related issues has already been presented prior to this, there is no need for repetition here.45

An outline of the law of divorce should be understood in light of the following points:

Since marriage is a civil agreement, it may be terminated as well, but Islām has only permitted this in extreme circumstances, when no other option exists. The Holy Prophet(sa) would state:

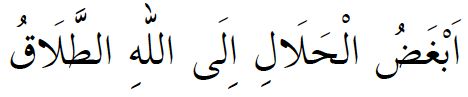

“Divorce is most undesirable in the sight of God among the things which Divine law has permitted as being lawful under special circumstances.”46

By way of this principle, Islām has given marital relations a kind of sanctity and perpetuity. Muslims have been instructed to never act hastily in severing this relation of marriage, rather, to practice extreme caution. However, despite this, in its capacity as a complete and universal Sharī‘at, Islām has not disregarded that sometimes such circumstances may arise which make it impossible to maintain a pleasant nature in the relations between husband and wife; not only does the domestic life of husband and wife become bitter, rather, this bitterness definitely influences the other aspects of their lives. In these circumstances, there is no other alternative but to end such a relationship with a saddened heart. It is taking extreme circumstances of this very nature into account that God the Exalted has instituted the law of divorce in Islām.

The law of divorce has primarily been divided into three parts (we shall put aside such cases of marriage which are against the Sharī‘at or unlawful, and are known as Nikāḥ-e-Bāṭil or Nikāḥ-e-Fāsid according to specific terminology):

Fasakh-e-Nikāḥ: I shall move away from the general terminology of Islāmic jurisprudence, and include cases of Li‘ān, etc. under this category as well. In other words, this refers to all such cases where it becomes unlawful to maintain a bond of marriage.

Ṭalāq: Where the desire of separation or submission for divorce is made by the husband.

Khula‘: Where the desire of separation or submission for divorce is made by the wife.47

In all the above-mentioned cases, Islām has prescribed different procedures.

The state of Fasakh-e-Nikāḥ comes about when it becomes unlawful to further continue a marriage. For example, if a girl exercises her right of Khiyārul-Bulūgh,48 which has been elaborated upon to some extent above. Similarly, if a husband becomes firmly convinced of the illicit relations of his wife but is unable to prove it according to the Sharī‘at, Islām commands that both the husband and wife take a firm oath against one another calling down the punishment of God upon themselves if they are liars. After this, they shall be separated. This is referred to as Li‘ān in Islāmic terminology.49

In the case of Ṭalāq, Islām instructs that when such circumstances arise between husband and wife where the husband becomes inclined to seek a separation from his wife, before he gives a divorce, the relatives of both parties should be given an opportunity to arbitrate between the two.50 If this effort proves successful, then well and good, but if not, the husband has the right to give a divorce of his own accord without going to the courts.51 However, this divorce should be given in such a period of Ṭuhr,52 where husband and wife have not had intimate relations.53 This is to prevent a rash decision, so that an individual does not just give a divorce without thinking, and so that the unique attraction of a wife remains open to deter a husband from his intention.

Although separation between a husband and wife may be materialised with only a single Ṭalāq, a husband has the right to withdraw his submission only until Ṭalāq has been issued twice. For complete separation to take place, it is necessary that a Ṭalāq be issued three times on three different occasions, so that irrevocable separation does not occur due to a step taken in a state of temporary anger, and a husband receives the opportunity to contemplate the consequences in his calmer moments. If a person issues a Ṭalāq three times all at once in the spur of emotions, this shall be deemed unlawful and only constitute a single Ṭalāq.54

In the case of Ṭalāq, if a husband has not yet paid the dowry owed to his wife, it is compulsory for him to do so. Furthermore, if he has given any other wealth to his wife, he must not demand its return either; rather, if possible, he should give her something in addition and bring the relationship to a close in a very pleasant and benevolent manner.55

Even after the divorce has taken place, the husband is responsible to bear the expenses of his divorcee until she becomes free to marry someone else.56 Furthermore, if there are young children who cannot be separated from their mother, they shall remain with her and the father shall be responsible for their necessary expenses.57

Then there is the Islāmic law of Khula‘. The leadership of domestic administration is in the hands of the husband, i.e., in light of the Sharī‘at and rationality, not only is the husband responsible for the expenses of his wife, rather, he is also the head of the family. Then, on the other hand, a woman is comparatively simple in nature and can be lured into the trickery of cunning people more easily. For this reason, a woman does not have the right to separate on her own. Instead, the Islāmic teaching is that if for some reason a woman feels it is no longer possible to continue living with her husband, and the husband is not prepared to give her a separation, she can attain a separation through a judge.58 A judge has been assigned the responsibility that if a woman actually desires a divorce, and she is not being lured into deceit or mischief, then he should order a separation and not be overly intrusive as to whether the woman’s desire for a separation is appropriate and preferable or not.59 According to this principle, if a woman finds it unbearable to accept the second marriage of her husband, she can demand a Khula‘ merely on these grounds.60

If a husband has given his wife a certain amount of wealth or property in addition to her daily expenses, and he demands the return of these valuables, in the case of Khula‘, the court can order the return of these assets to a reasonable extent.61

In the cases of Fasakh-e-Nikāḥ, Ṭalāq and Khula‘, where husband and wife are separated after having come together, the wife is not permitted to marry again until a fixed period has elapsed since the separation. Generally, this period is equivalent to about three months, or if the wife is pregnant, then until she delivers. In the terminology of Sharī‘at, this period is referred to as an ‘Iddat.62

This is an outline of the law of marriage and divorce as instituted by the Holy Prophet(sa) for the Muslims according to Divine command. In this system, the merit of the law of marriage has always been accepted to be wise and sensible. However, it is a matter of gratitude that after centuries of stumbling, the world is now slowly and gradually coming towards the Islāmic law of divorce as well. As such, in many Christian countries, the law of divorce is being more or less introduced according to the lines proposed by Islām. However, an apprehension also exists that as per the custom of western nations, divorce may also become very common, i.e., lest the door of freedom be opened to people beyond a middle course. On the one hand, to completely close the door of divorce, or attach such unreasonable conditions to it, that it is practically equivalent to being closed, is extremely detrimental. On the other hand, however, to open the door completely is also not without its injurious effects. Most definitely, the path of reform is the balanced one which has been prescribed in Islām.

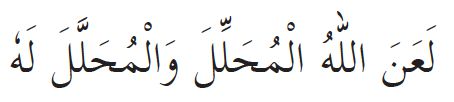

At this instance, it would not be without benefit to mention that Mr. Muir63 has offensively taunted that according to the Islāmic law of divorce until two divorces have been issued, a husband has the right to return to his wife, but after a third divorce, the right of return only exists after a woman first marries another person and then divorces him. After this, with great audacity Mr. Muir states that it is permissible among the Muslims to employ the services of another man and marry off such a woman to a man of this nature on the condition that he shall divorce her after marriage, so that the woman may return to her actual husband. This allegation is based on prejudice of the highest degree, and if not, then remarkable ignorance. Islām does not at all teach that in order to make a woman lawful for her previous husband the deceitful strategy be employed whereby a woman is married to another man only to be later separated. On the contrary, the fact of the matter is that Islām has declared such trickery to be an extremely vile and cursed act. The Holy Prophet(sa) would state:

“Such a person is accursed by God who marries a woman with the intention that he shall later divorce her so that she may become lawful for her previous husband. Similarly, such a person is also accursed by God who marries his previous wife to another individual with the intention that such a person shall divorce her and she may be able to marry him again.”

Ḥaḍrat ‘Umar(ra), the second Khalīfah would even state that if an individual had committed such a crime, such a person would be punished for adultery.64 In these circumstances, what greater example of insolence can there be than to attribute such a foul practice to Islām.

The intention behind the Islāmic teaching, is not as Mr. Muir has understood, or perhaps he has chosen not to understand. When three divorces have been issued, a man and woman cannot come together again until the woman marries another man for a legitimate need and purpose. If afterwards, her new husband passes away or a real dispute arises between the two and there is a divorce, and this marriage was not for the purpose that the woman may return to her former husband, in such a case, the previous husband is permitted to marry a former wife with mutual agreement. The wisdom behind this teaching is that when an individual gives his wife three divorces consecutively, after this lengthy experience it shall be understood that now it is impossible for their marital life to continue in a pleasant manner. Hence, they should not come together and further prolong a bitter experience. Instead, they should separate completely and remove the idea from their hearts that they can live together. After this, however, if a woman marries another man and lives a domestic life with him, and a separation takes place with her new husband for a genuine reason threafter, or he passes away, there should be no hindrance in the woman marrying her previous husband if both desire to come together again with mutual agreement. The reason being that in addition to the fact that there is no reason in principle for the prohibition of their marriage, in such a case, it would not be improbable at all to assume that now, they would be able to live together harmoniously. Due to their remaining apart from one another and having dealt with a third party, it is absolutely possible for them to begin recognising the value of one another. Furthermore, it is most probable and due to the same purpose that this issue has been especially expounded in Islām as well. On the one hand, where the bitter experiences of domestic life should be minimized, on the other hand, the notion should also be removed among people that the issuance of three divorces in itself is a reason for prohibition and that after three divorces there is no possibility for the reunion of husband and wife.

In addition to this, another wisdom in keeping the door open for the renewal of marriage is so that people are made to recognise the sanctity and perpetuity of marriage, and the concept may be instilled that when marital relations are established between a man and woman, an extreme effort to safeguard this relationship must be exerted. If, due to some reason, this relation is severed in between, and it becomes unlikely that it shall ever be re-established, even still, when an opportunity to legally re-establish this bond presents itself, it should not be wasted. Therefore, the issue which Mr. Muir has made reference to in a false and filthy manner and then levelled an allegation against, is actually, in its true form, a very great quality of the Islāmic doctrine. However, it is unfortunate that the eye of Sir William was unable to identify this.

1 An-Nisā’ (4:23)

2 An-Nisā’ (4:20)

3 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Man Qāla Lā Nikāḥa Illā Bi-Waliyyin, Ḥadīth No. 5127

4 Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fir-Rajuli Yuslimu Wa ‘Indahū ‘Ashru Niswatin, Ḥadith No. 1128

5 Al-Baqarah (2:233)

6 Al-Muwaṭṭā, By Imām Mālik bin Anas, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Jāmi‘i Mā Lā Yajūzu Minan-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 1137

7 Al-Baqarah (2:229)

8 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fil-Īlā’i Wa I‘itizālin-Nisā’i Wa Takhyīrihinna....., Ḥadīth No. 3691

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fī Ḍarbin-Nisā’i, Ḥadīth No. 2145

9 Al-Baqarah (2:233/238)

An-Nisā’ (4:21/22)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābush-Shurūṭi Fin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 5151

10 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābush-Shurūṭi Fin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 5151

11 Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:1-8)

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fī Ṭalāqis-Sunnah, Ḥadīth No. 2179

12 An-Nisā’ (4:4)

An-Nūr (24:32-34)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābut-Targhībi Fin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 5063

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Qaulin-Nabiyyi(sa) Manistaṭā‘a Minkumul-Bā’ata....., Ḥadīth No. 5065

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Yukrahu Minat-Tabattuli Wal-Khiṣā’i, Ḥadīth No. 5073

13 Refer to the discussion on polygamy under the accounts of 2 A.H., in this very book.

14 An-Nisā’ (4:24-26)

15 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Chapters 21-28

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 783-789, Faṣlun: Fī Mā Ḥakamallāhu Subḥānahū Bi-Taḥrīmi Minan- Nisā’i ‘Alā Lisāni Nabiyyihisa (Entire Chapter), Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

16 An-Nisā’ (4:2 and 4:20-21)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Lā Yunkiḥul-Abu Wa Ghairuhul-Bikra Wath-Thayyiba Illā Bi-Riḍāhā, Ḥadīth No. 5136

Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Isti’dhānith-Thayyibi Fin-Nikāḥi Bin-Nuṭqi Wal-Bikri Bis- Sukūti, Ḥadīth No. 3473

17 An-Nisā’ (4:2/4)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābun-Naẓari Ilal-Mar’ati Qablat-Tazwīj, Ḥadīth No. 5126

Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fin-Naẓari Ilal-Makhṭūbah, Ḥadīth No. 1087

18 Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fī I‘lānin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadith No. 1089

Al-Muwaṭṭā, By Imām Mālik bin Anas, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Jāmi‘i Mā Lā Yajūzu Minan-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 1136

19 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Various chapters from Bābul-Walīmatu Haqqun to Bābu Ijābatid- Dā‘iyyi Fil-‘Ursi, Ḥadīth No. 5126

20 Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:1-8)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Inkāḥir-Rujuli Waladahuṣ-Ṣighār, Ḥadīth No. 5133

21 The fundamental principle behind this right has been alluded to in the Holy Qur’ān, where it has been expounded that a woman takes a strong covenant from her husband - refer to An-Nisā’ (4:20- 22). This cannot occur unless a girl has the right to choose whether she desires to maintain the bond of marriage or end it upon reaching an age of maturity, if the marriage has been settled in childhood. Furthermore, refer to Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fī Ikrāhil-Yatīmati ‘Alat-Tazwīji, Ḥadīth No. 1109

22 Al-Baqarah (2:224-229)

Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābu Tafsiril-Qur’ān, Bābu Wa Min Sūratil-Baqarah, Ḥadīth No. 2980

23 Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fil-Waliyyin, Ḥadīth No. 2083/2085

Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Lā Nikāḥa Illā Bi-Waliyyin, Ḥadīth No. 1101-1102

24 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Idhā Zawwajar-Rajulu Ibnatahū Wa Hiya Kārihatun Fa- Nikāḥuhū Mardūdun, Ḥadīth No. 5138

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fil-Bikri Yuzawiijuhā Abūhā Wa Lā Yasta’miruhā, Ḥadīth No. 2096

25 Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Lā Nikāḥa Illā Bi-Waliyyin, Ḥadīth No. 1102

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fil-Waliyyin, Ḥadīth No. 2083

26 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Isti’dhānith-Thayyibi Fin-Nikāḥi Bin-Nuṭqi Wal-Bikri Bis- Sukūti, Ḥadīth No. 3476

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fith-Thayyib, Ḥadīth No. 2098

27 An-Nisā’ (4:25-26)

Al-Baqarah (2:238)

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābuṣ-Ṣadāq, Al-Faṣluth-Thānī, Ḥadīth No. 3206, p. 588, Dārul- Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

28 An-Nisā’ (4:12)

29 An-Nisā’ (4:13)

30 Al-Baqarah (2:234)

An-Nisā’ (4:35)

Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:7-8)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nafaqāt, Bābu Ḥabsir-Rajuli Qūta Sanatin ‘Alā Ahlihi....., Ḥadīth No. 5357

Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābul-Ḥajj, Bābu Hajjatin-Nabiyyi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 2950

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fī Ḥaqqil-Mar’ati ‘Alā Zaujihā, Ḥadīth No. 2143

31 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābush-Shurūṭi Fin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 5151

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābush-Shurūṭillati Lā Taḥillu, Ḥadīth No. 5152

Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fish-Sharṭi ‘Inda ‘Uqdatin-Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 1127

32 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Idhashtaraṭa Shurūṭan Fil-Bai‘i Shurūṭan Lā Taḥillu, Ḥadīth No. 2168

33 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābush-Shurūṭillati Lā Taḥillu, Ḥadīth No. 5152

34 Al-Muwaṭṭā, By Imām Mālik bin Anas, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Lā Yajūzu Minash-Shuruṭi Fin- Nikāḥ, Ḥadīth No. 1125

Chashma-e-Ma‘rifat, Rūḥānī Khazā’in, Volume 23, pp.237-238

35 Al-Baqarah (2:229)

36 An-Nisā’ (4:20-21)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Ḥusnil-Mu‘āsharati Ma‘al-Ahli, Ḥadīth No. 5189

37 An-Nisā’ (4:35)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Mā Yukrahu Min Ḍarbin-Nisā’i, Ḥadīth No. 5204

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fī Ḥaqqil-Mar’ati ‘Alā Zaujihā, Ḥadīth No. 2142

38 Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu ‘Ishratin-Nisā’, Al-Faṣluth-Thānī, Ḥadīth No. 3252, p. 597, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābul-Manāqib, Bābu Faḍli Azwājin-Nabiyyi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 3895

Sunanud-Dārimī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fī Ḥusni Mu‘āsharatin-Nisā’, Ḥadīth No. 2264

39 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābur-Riḍā‘i, Bābul-Waṣiyyati Bin-Nisā’i, Ḥadīth No. 5186

40 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Waṣāti Bin-Nisā’, Ḥadīth No. 5186

41 An-Nisā’ (4:35)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Ilā Man Yankiḥa Wa Ayyun-Nisā’i Khairun....., Ḥadīth No. 5082

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Kufrānil-‘Ashīr Wa Kufrin Dūna Kufrin....., Ḥadīth No. 29

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābun Al-Mar’atu Rā‘iyatun Fī Baiti Zaujihā....., Ḥadīth No. 2500

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Lā Tuṭī‘ul-Mar’atu Zaujahā Fī Ma‘ṣiyatin....., Ḥadīth No. 5205

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu ‘Ishratin-Nisā’, Volume 1, pp. 594-600, Dārul-Kutubil- ‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

42 Al-Baqarah (2:229)

43 Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu ‘Ishratin-Nisā’, Al-Faṣluth-Thālith, Ḥadīth No. 3269, Volume 1, p. 599, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

44 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fil-Īlā’i Wa I‘tizālin-Nisā’i....., Ḥadīth No. 3695

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābu Fī Ḍarbin-Nisā’i....., Ḥadīth No. 2145

45 Refer to the events of 2 A.H. in this book

46 Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fī Karāhiyyatiṭ-Ṭalāq, Ḥadīth No. 2178

47 Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula’i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣlul-Awwal, Ḥadīth No. 3274, Volume 1, p. 600, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula’i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣluth-Thānī, Ḥadīth No. 3280, Volume 1, p. 601, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Li‘ān, Al-Faṣlul-Awwal, Ḥadīth No. 3304, Volume 1, p. 606, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 812-813, Ḥukmu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Fil-Khula‘, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), p. 845, Ḥukmu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Bi Annaṭ-Ṭalāq Bi Yadiz-Zauji Lā Bi Yadi Ghairihī, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 874-876, Ḥukmu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Fil-Li‘ān, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

48 Bidāyatul-Mujtahidi Wa Nihāyatul-Muqtaṣid, By Abul-Walīd Muḥammad bin Aḥmad bin Muḥammad (Ibni Rushd), Al-Bābuth-Thānī Fī Mūjibāti Siḥḥatin-Nikāḥ, p. 440, Fārān Academy Lahore

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 775-776, Dhikru Aqḍiyatihī Wa Aḥkāmihī(sa) Fin-Nikāḥ....., Faṣlun Fī Ḥukmihī(sa) Fith-Thayyibi Wal-Bikri Yuzawwijuhumā Abūhumā, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

49 An-Nūr (24:5-11)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābut-Tafrīqi Bainal-Mutalā‘inīn, Ḥadīth No. 5313

50 An-Nisā’ (4:36)

51 Al-Baqarah (2:230-232)

An-Nisā’ (4:36)

AṬ-Ṭalāq (65:1-5)

52 A term of Islāmic Jurisprudence, which refers to the specific period of the month, in which the Sharī‘at permits husband and wife to engage in intercourse. [Publishers]

53 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Qaulillāhi Ta‘ālā Yā Ayyuhannabiyyu Idhā Ṭallaqtumun- Nisā’a....., Ḥadīth No. 5251

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābut-Tafsīr, Tafsiru Sūratiṭ-Ṭalāq, Ḥadīth No. 4908

54 Al-Baqarah (2:230-232)

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fil-Battah, Ḥadīth No. 2206

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Wa Bu‘ūlatuhunna Aḥaqqu Bi-Raddihinna, Ḥadīth No. 5332

Sunanun-Nasa’ī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Ath-Thalālul-Majmū‘atu Wa Mā Fīhi Minat-Taghlīẓ, Ḥadīth No. 3401

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula’i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣlul-Awwal, Ḥadīth No. 3275, Volume 1, pp. 600-601, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula’i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣluth-Thānī, Ḥadīth No. 3283, Volume 1, p. 602, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula’i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣluth-Thālith, Ḥadīth No. 3292, Volume 1, p. 603, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

55 Al-Baqarah (2:230-232)

Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:1-8)

56 Al-Baqarah (2:234)

Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:1-8)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Qiṣṣati Fāṭimata Binti Qaisin, Ḥadīth No. 5323-5326

Bidāyatul-Mujtahidi Wa Nihāyatul-Muqtaṣid, By Abul-Walīd Muḥammad bin Aḥmad bin Muḥammad (Ibni Rushd), Al-Bābul-Awwalu Fil-‘Iddati, Al-Faṣlul-Awwalu Fī ‘Iddatiz-Zaujāti, Al- Qismuth-Thānī, pp. 511-513, Fārān Academy Lahore

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 943-944, Faṣlun Fī Ḥukmi Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Muwāfiqi Li-Kitabillāhi Annahū Lā Nafaqata Lil-Matbūtati Wa Lā Saknā / Dhikrul-Maṭā‘inillati Ṭu‘ina Bihā ‘Alā Ḥadīthi Fāṭimata Binti Qaisin Qadīman Wa Ḥadīthan, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

57 Al-Baqarah (2:234)

Al-Muwaṭṭā, By Imām Mālik bin Anas, Kitābul-Waṣiyyah, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fil-Mu’annathi Minar-Rijāli Wa Man Aḥaqqu Bil-Waladi, Ḥadīth No. 1498

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Man Aḥaqqu Bil-Waladi, Ḥadīth No. 2276

Bidāyatul-Mujtahidi Wa Nihāyatul-Muqtaṣid, By Abul-Walīd Muḥammad bin Aḥmad bin Muḥammad (Ibni Rushd), Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Al-Bābur-Rābi‘u Fī Ḥuqūqiz-Zaujiyyati, p. 481, Fārān Academy Lahore

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 905-907, Faṣlu Dhikri Ḥukmi Rasūlillāhi(sa) Fil-Waladi Man Aḥaqqu Bihī Fil-Ḥaḍānah, Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

58 Al-Baqarah (2:230-231)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula‘

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Bābul-Khula‘ Wa Bābul-Waliyyi Fin-Nikāḥ, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2003)

Bidāyatul-Mujtahidi Wa Nihāyatul-Muqtaṣid, By Abul-Walīd Muḥammad bin Aḥmad bin Muḥammad (Ibni Rushd), Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Bābuth-Thālithu Fil-Khula‘i, Al-Faṣluth-Thānī Fī Shurūṭi Wuqū‘ihī, Al-Qismuth-Thānī, p. 492, Fārān Academy Lahore

Zādul-Ma‘ādi Fī Hadyi Khairil-‘Ibād, By Shamsuddīn Abū ‘Abdillāh Muḥammad bin Abī Bakr (Ibni Qayyim Al-Jauziyyah), pp. 812-813, Ḥukmu Rasūlillāhi Fil-Khula‘i....., Mu’assisatur-Risālah, Beirut, Lebanon (2006)

59 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābul-Khula‘i Wa Kaifaṭ-Ṭalāqu Fīhi, Ḥadīth No. 5273

Sunanu Abī Dāwūd, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābu Fil-Khula‘, Ḥadīth No. 2227

60 Chashma-e-Ma‘rifat, Rūḥānī Khazā’in, Volume 23, p. 247

Kishtī-e-Nūḥ, Rūḥānī Khazā’in, Volume 19, p. 81

61 Al-Baqarah (2:230-)

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābuṭ-Ṭalāq, Bābul-Khula‘i Wa Kaifaṭ-Ṭalāqu Fīhi, Ḥadīth No. 5273

Mishkātul-Maṣābīḥ, Bābun-Nikāḥ, Bābul-Khula‘i Waṭ-Ṭalāq, Al-Faṣlul-Awwal, Ḥadīth No. 3274, Volume 1, p. 600, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut,

62 Al-Baqarah (2:229)

Al-Aḥzāb (33:50)

Aṭ-Ṭalāq (65:7-8)

63 The Life of Mahomet, By Sir William Muir, Chapter XVII (Divorce thrice repeated irrevocable), pp. 349-350, Published by Smith, Elder & Co. London (1878)

64 Tafsīrul-Qur’ānil-‘Aẓīm (Tafsīru Ibni Kathīr), By ‘Imāduddīn Abul-Fidā’ Ismā‘īl bin ‘Umar Ibni Kathīr, Volume 1, p. 474, Tafsīru Sūratil-Baqarah, Under verse 231 “Fa’in Ṭallaqahā Falā Taḥillu Lahū Mim- Ba‘du Ḥattā Tankiḥa Zaujan Ghairahū....., Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon (1998)