After the continuous labour of more or less twenty days1, or in light of one narration, after six days of work day and night,2 the ditch was completed. The Companions were absolutely exhausted as a result of this extraordinary effort and labour. However, as soon as this work was completed, the Jews and idolators of Arabia dawned upon the horizon of Madīnah, intoxicated by their number and strength, with their army and baggage. Before anything else, Abū Sufyān advanced towards the mount of Uḥud. Upon finding this place deserted and abandoned, he marched towards that part of Madīnah, which was best suited for an attack upon the city, but had now been surrounded by a ditch. When the army of the disbelievers reached this place, upon confronting the hindrance of a ditch on their route, everyone was left astonished and confounded. They were compelled, therefore, to setup camp on the plain beyond the ditch. On the opposing front, upon receiving news of the imminent arrival of the disbelieving army, the Holy Prophet(sa) set out from the city with 3,000 Muslims and when he neared the ditch, he positioned himself between the city and the ditch in such a manner that the mount of Sala‘ was to his rear.3 The ditch, however, was not very wide and definitely, there were certain areas from where strong and experienced riders could have managed to leap over into the city. Furthermore, there were also fronts of Madīnah which were not guarded by the ditch, and the only barrier that existed there was of homes, orchards and large rocks, which were unevenly spaced. Naturally, it was necessary to secure these areas, in order to prevent the enemy from destroying these homes or entering into the city in smaller groups and waging an attack by some other strategy. Hence, the Holy Prophet(sa) divided the Companions into various detachments and positioned them to stand guard on different posts in appropriate locations at the ditch and on the other fronts of Madīnah. The Holy Prophet(sa) stressed that be it day or night, this security should not fall weak or inattentive.4 At the opposing end, when the disbelievers noticed that due to the barrier of the ditch, it was now impossible to fight a battle in an open field or wage an all out attack on the city, they surrounded Madīnah in the form of a siege and began to search for opportunities to exploit the weaker sections of the ditch.

In addition to this, another tactic which Abū Sufyān employed was that he instructed Ḥuyayy bin Akhṭab, the Jewish chief of Banū Naḍīr, to go to the fortresses of Banū Quraiẓah in the veils of the darkness of night and attempt to bring over the Banū Quraiẓah with the aid of their chief, Ka‘b bin Asad.5 Therefore, Ḥuyayy bin Akhṭab found an opportunity and arrived at the home of Ka‘b. Initially, Ka‘b refused and said that “We have settled a covenant and agreement with Muḥammad[sa], and he has always loyally fulfilled his covenants and agreements, therefore, I cannot act treacherously towards him.” However, Ḥuyayy painted a picture of lush green gardens to him and gave him such confidence in the imminent destruction of Islām; and presented their own resolve with such force and emphasis that they would not return from Madīnah until they had obliterated Islām, that ultimately, he agreed.6 In this manner, the strength of the Banū Quraiẓah also added to the weight on a scale which was already heavily weighed to one side. When the Holy Prophet(sa) received news of this dangerous treachery of the Banū Quraiẓah, initially, the Holy Prophet(sa) dispatched Zubair bin Al-‘Awwām(ra) to obtain intelligence in secret two or three times.7 Then, after this, the Holy Prophet(sa) formally sent Sa‘d bin Mu‘ādh(ra) and Sa‘d bin ‘Ubādah(ra), who were chieftains of the Aus and Khazraj tribes along with a few other influential Companions in the form of a delegation towards the Banū Quraiẓah; and strictly instructed that if there was troubling news, it should not be publicly disclosed when they returned, rather, secrecy should be maintained so that people were not made apprehensive. When these people reached the dwellings of Banū Quraiẓah and approached Ka‘b bin Asad, this evil man confronted them in a very arrogant manner. When the two Sa‘ds spoke of the treaty, Ka‘b and the people of his tribe turned wicked and said, “Be gone! There is no treaty between Muḥammad[sa] and us.” Upon hearing these words, this delegation of Companions set off. Sa‘d bin Mu‘ādh(ra) and Sa‘d bin ‘Ubādah(ra) then presented themselves before the Holy Prophet(sa) and informed him of the state of affairs in an appropriate manner.8

At this time, as far as apparent means were concerned, the horizon of Madīnah was immensely dark and gloomy. On all four fronts of the city, thousands of bloodthirsty enemies had setup camp. All of them lay in ambush to find an opportunity so that they could pounce at the Muslims and annihilate them. Within the city, at arms reach of the Muslims, were the treacherous Banū Quraiẓah, who were no less than a fierce army in themselves, boasting hundreds of armed young men. They were in a position to attack the Muslims from the rear whenever they so pleased or whenever an opportunity presented itself. The Muslim women and children, who resided in the city, were easy prey for them at all times. As a result of this state of affairs, and the reality of this cannot remain hidden upon any wise individual, immense fear and terror surged through the weaker Muslims, and the hypocrites openly criticized:

“It seems as if the promise of God and His Messenger with respect to the victory and triumph of the Muslims was nothing but lies.”9

Various hypocrites presented themselves before the Holy Prophet(sa) and began to say, “O Messenger of Allāh, our homes are completely unprotected in the city, please grant us permission so that we may stay in our homes to defend them.” In response to this, the following divine revelation was sent down:

“It is incorrect that these people are worried about their homes being exposed, rather, the fact of the matter is that they seek a way to flee from the field of battle.”10

It was at this very juncture, however, that sincere Muslims exhibited the true colours of their faith. As such, the Holy Qur’ān states:

“And when the believers saw the army of the disbelievers, they said, ‘This is what Allāh and His Messenger promised us; and indeed, Allāh and His Messenger are truthful. Hence, this onslaught only added to their faith and submission.”11

However, all equally felt the vulnerable situation and threatening circumstances at hand. In this regard, Allāh the Exalted states:

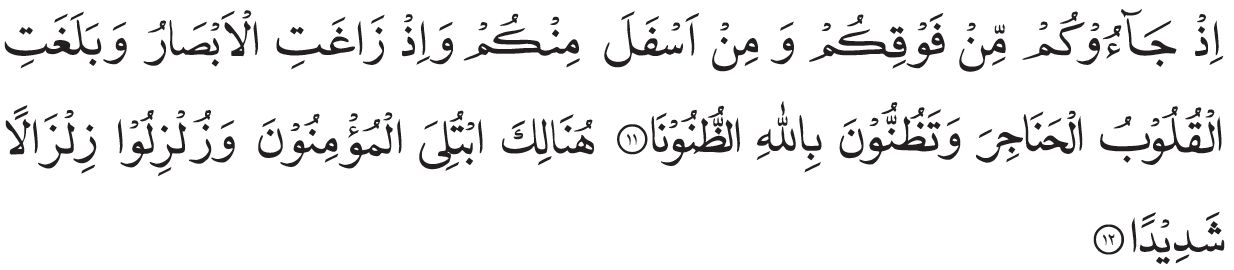

“Remember the time when the army of the disbelievers came upon you from above you, and from below you in hordes, and when your eyes became overwhelmed with anxiety, and your hearts came to your throats, and you began to entertain diverse thoughts about Allāh (all in your own way). That time, was indeed a time of sore trial for the believers, and they were shaken with a violent shaking.”12

At such a perilous time, how could this small group of Muslims contest, who consisted of various weaker dispositions and hypocrites as well? They did not even have enough men to adequately arrange to stand guard at less secure posts. As a result, this harsh duty of day and night utterly exhausted the Muslims. On the other hand, due to the treachery of the Banū Quraiẓah, it was necessary to strengthen security in the streets and alleys of the city as well, so that the women and children could be protected. The disbelieving warriors exhausted every possible avenue in an attempt to agonise the Muslims. At times, they would gather at a weaker point and launch an attack and the Muslims would be forced to regroup there in denfese. At this, the disbelievers would immediately redirect their strength and press another point and the poor Muslims would make haste in that direction. On other occasions, they would wage an attack at two or three points simultaneously and the Muslim force would be dispersed into smaller fragments. At times, the course of events would take on an extremely delicate state and the disbelieving army almost penetrated the weaker points to enter the city. These full-fledged attacks were generally warded off by the Muslims with arrows. However, at times, a strategy employed by the disbelieving warriors was that one contingent would shower the Muslims with arrows to hold them back, while another contingent would storm a weaker point of the ditch and wage a general attack, in an attempt to cross over.13 This method of warfare would continue from dawn till dusk, and sometimes it would even carry on during parts of the night. An account spanning two days of this battle has been put to writing by Sir William Muir in the following words:

“The enemy, notwithstanding their numbers, were paralysed by the vigilance of the Moslem outposts......The confederate army resolved if possible to storm it, and, having discovered a certain narrow and weakly-guarded part, a general attack was made upon it. The cavalry spurred their horses forward, and a few of them, led by Ikrima son of Abū Jahl cleared the ditch, and galloped vauntingly in front of the enemy. No sooner was this perceived than Ali with a body of picked men moved out against them. These, by a rapid manoeuvre, gained the rear of Ikrima, and, occupying the narrow point which he had crossed, cut off his retreat. At this moment Amr son of Abd Wudd, an aged chief in the train of Ikrima, challenged his adversaries to single combat. Ali forthwith accepted the challenge, and the two stood alone in an open plain. Amr, dismounting, maimed his horse, in token of his resolve to conquer or to die. They closed, and for a short time were hidden in a cloud of dust. But it was not long before the well-known Takbîr, ‘Great is the Lord!’ from the lips of Ali, made known that he was the victor. The rest, taking advantage of the diversion again spurred their horses, and all gained the opposite side of the trench, excepting Nowfal, who, failing in the leap, was despatched by Zobeir. The Coreish, it is said, offered a great sum for the body;14 but Mahomet returned the ‘worthless carcass’ (as he termed it) free. Nothing further was attempted that day. But great preparations were made during the night; and next morning, Mahomet found the whole force of the Allies drawn out against him. It required the utmost activity and an unceasing vigilance on his side to frustrate the manoeuvres of the enemy. Now they would threaten a general assault; then breaking up into divisions they would attack various posts in rapid and distracting succession; and at last, watching their opportunity, they would mass their troops on the least protected point, and, under cover of a sustained and galling discharge of arrows, attempt to force the trench. Over and again a gallant dash was made at the city, and at the tent of Mahomet, by such leaders of renown as Khâlid and Amru; and these were only repelled by constant counter-marches and unremitting archery. This continued throughout the day; and, as the army of Mahomet was but just sufficient to guard the long line, there could be no relief. Even at night Khâlid, with a strong party of horse, kept up the alarm, and, still threatening the line of denfese, rendered outposts at frequent intervals necessary. But all the endeavours of the enemy were without effect. The trench was not crossed; and during the whole affair Mahomet lost only five men. Sád ibn Muâdz, chief of the Bani Aus, was wounded severely by an arrow in the shoulder. The archer, as he shot it, cried aloud: ‘There, take that from the son of Arca’.......The Confederates had but three men killed. No prayers had been said that day: the duty at the trench was too heavy and incessant. When it was dark, therefore, and the greater part of the enemy had retired to their camp, the Moslem troops assembled, and a separate service was repeated for each prayer which had been omitted. Mahomet on this occasion cursed the allied army, and said: ‘They have kept us from our daily prayers: God fill with fire their bellies and their graves!’”15

In this interesting note of Mr. Muir, where he has stated that all of the prayers of the Muslims were not offered on time is incorrect. Quite the contrary, all that is substantiated by authentic narrations is that until that time, since Ṣalāt-e-Khauf had not been prescribed as yet, due to the continuous threat and engagement, only one prayer, i.e., ‘Aṣr prayer could not be offered in time and was combined with Maghrib.16 In light of certain narrations, only the Ẓuhr and ‘Aṣr prayers were offered later than usual.17

In addition to this, the account which relates to the battle of Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) and ‘Amr bin ‘Abdi Wudd as described by Mr. Muir is very brief. History has recorded this encounter with great detail and certain aspects of this account are very interesting. ‘Amr was an extremely renowned swordsman and due to his bravery, was considered to be the like of 1,000 warriors by himself.18 Since he had returned from Badr frustrated and unsuccessful, his heart was satiated with feelings of malice and revenge. As soon as he took to the field, he called for a duel in a very arrogant manner.19 Certain Companions were reluctant in confronting him, but Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī stepped forward to square up to him with the permission of the Holy Prophet(sa).20 The Holy Prophet(sa) bestowed his own sword to him and prayed for him.21

Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) advanced and said to ‘Amr, “I have heard that you have vowed that if a person from the Quraish requests two things of you, you shall accept one of the two.” “Indeed,” said ‘Amr. Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) responded, “Then I ask you first to embrace Islām and become the recipient of divine favours by accepting the Holy Prophet(sa).” “This is not possible,” said ‘Amr. Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) said, “If not this, then come forward and prepare to battle me.”22 At this, ‘Amr began to laugh and said, “I did not believe that anyone would ever muster the courage to say such words to me.”23 Then he asked Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī to provide his name and line of decent, and upon hearing his descent, said, “Nephew! You are still a child. I do not wish to spill your blood, send forth your elders.”24 “You do not wish to spill my blood,” said Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra), “but I feel no hesitation in spilling your blood.”25 Upon hearing this, ‘Amr became blind in rage and after jumping from his horse, hamstrung it. Then he madly marched forward towards Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) like a fierce flame of fire and wielded his sword against him with such force, that it cut through the shield of Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) and struck his forehead, who was wounded to some extent. However, Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) retaliated with such lightning speed, calling out a slogan of God’s Greatness, that ‘Amr was left fending for his life. The sword of Ḥaḍrat ‘Alī(ra) penetrated his shoulder and cut him to the ground. ‘Amr fell to the ground and gave up his life tossing and turning in agony.26

However, this secondary and temporary victory did not affect the battle on the whole. These days were ones of grave pain, apprehension and danger. As the siege grew longer and longer, the Muslims naturally began to lose their strength to fight and although they were full of faith and sincerity, their bodies, which of course functioned according to the material law of nature, began to fall weak. When the Holy Prophet(sa) witnessed this state of affairs, he called upon the two chieftains of the Anṣār, Sa‘d bin Mu‘ādh(ra) and Sa‘d bin ‘Ubādah(ra) and recalling to them all of the circumstances at hand sought their counsel. The Holy Prophet(sa) even proposed, “If you are in agreement, it is also possible that we may give the Ghaṭafān tribe a portion of our wealth, so that this war may be averted.” Sa‘d bin Mu‘ādh(ra) and Sa‘d bin ‘Ubādah(ra) resonated the same words, and submitted, “O Messenger of Allāh! If you have received divine revelation in this respect, then we bow before you in obedience. In this case, most definitely, let us act upon this proposition gladly.” The Holy Prophet(sa) said, “Nay, nay, I have not received any revelation in this matter. I only present this suggestion out of my consideration for the hardship you are being made to bear.” The two Sa‘ds responded, “Then our suggestion is that if we have never given anything to an enemy while we were idolators, why then should we do so as Muslims? By God! We shall give them nothing but the strikes of our swords.”27 The Holy Prophet(sa) was worried on account of the Anṣār, who were the native residents of Madīnah. Furthermore, in seeking this counsel, the only intent of the Holy Prophet(sa) was to perhaps gather insight into the mental state of the Anṣār, as to whether they were worried about these hardships or not, and if they were, then to console them. Thus, when this proposal was put forth, the Holy Prophet(sa) happily accepted and war continued. During the course of war, due to constant engagement and distress, many a time, the Holy Prophet(sa) and his Companions were made to face starvation. One day, the Companions came to the Holy Prophet(sa) and submitted to him the pains they were suffering due to starvation saying, “We have been walking about with stones tied to our stomachs for many days.” At this, the Holy Prophet(sa) lifted the cloth upon his own blessed stomach, which had two stones tied to it.28 This starvation, coupled with the other hardships of war, had put the Muslims in a very difficult situation. The apprehension of constant threat also took its toll on their hearts, minds, and nerves. Naturally, the greatest burden of this strain was upon the Holy Prophet(sa). Ummi Salamah(ra) relates that:

“I have accompanied the Holy Prophet(sa) on many Ghazwāt, but none were as severe as the Ghazwah of the Ditch. The Holy Prophet(sa) was compelled to bear extreme hardship and discomfort. The Companions were also confronted with extreme adversity. Furthermore, these days were of immense cold and financial hardship.”29

On the other hand, the Holy Prophet(sa) had generally gathered the women and children of the city in a special area, which could be likened to a fortress.30 However, a sufficient number of Muslims could not be made available to adequately protect them. Especially at such times when the enemy onslaught in the battlefield was at full force, the Muslim women and children would practically be left unguarded, and only such men would be left to protect them who for some reason or other, were unfit for the field of battle. Therefore, capitalising on a situation like the one just mentioned, the Jews proposed to attack one such area of the city where the women and children had gathered. These people sent a spy ahead of them to assess the situation in this quarter of the city. It so happened that the only person present near the women at the time was Ḥassān bin Thabit, the poet, who was unable to go to the battlefield due to his being very weak at heart.31 When the women noticed this Jewish enemy surveying their encampment in such a suspicious manner, Ṣafiyyah bint ‘Abdil-Muṭṭalib, the paternal-aunt of the Holy Prophet(sa), said to Ḥassān(ra), “This individual is an enemy Jew, who is prowling about to acquire intelligence and is bent upon mischief. Kill him, so that he does not return to his people and cause harm to us.” However, Ḥassān(ra) could not find the courage to do so. Therefore, Ḥaḍrat Ṣafiyyah moved forward herself and fought the Jew, after which she killed him and he fell to the ground.32 Then, according to her own proposal, the Jewish spy was beheaded and thrown to that side of the stronghold where the Jews had gathered, so that they would not dare to attack the Muslim women, and were made to believe that they were guarded by many men. Hence, this strategy proved to be successful. As a result, the Jewish people were awe-struck and turned back.33

This was a time of great tribulation for the Muslims. Distressed by this intense adversity, a few Companions presented themselves before the Holy Prophet(sa) and submitted, “O Messenger of Allāh! The state of affairs is evident to you. Our hearts are coming to our throats. Supplicate to God especially that He may remove this hardship and teach us a prayer as well which we may offer before God on this occasion.” The Holy Prophet(sa) comforted them and said, “Pray to Allāh that He may cover your weaknesses and strengthen your hearts, and remove your anxiety.”34 Then, the Holy Prophet(sa) offered the following supplication:

In another narration it is related that the Holy Prophet(sa) supplicated in the following words:

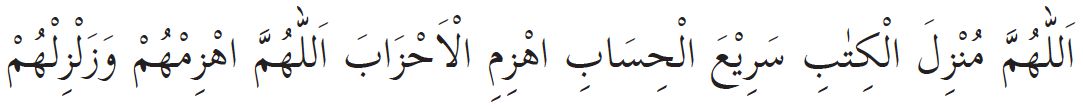

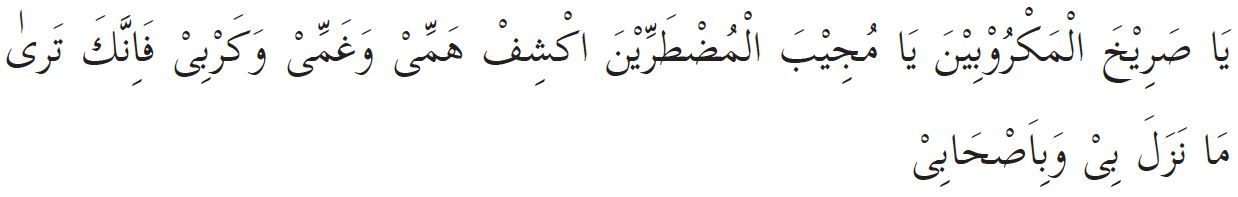

“O God, Who is the Revealer of commandments in the world! O You Who is Swift in calling to account! Send these disbelieving confederates to flight by Your Grace. O My Powerful God, put them to flight, and help us against the disbelievers, and shake their strength.35 O You Who listens to the cries of those who are in distress! O You Who listens to the supplications of the afflicted! Remove our grief, distress and anxiety, for you see the affliction that my Companions and I are confronted with at this time.”36

By good fortune, at that very moment, or around that time, an individual named Na‘īm bin Mas‘ūd who belonged to the Ashja‘ tribe, which was a branch of the Ghaṭafān tribes, and was fighting against the Muslims in this war, reached Madīnah. In his heart, this person had accepted Islām, but until now, the disbelievers were unaware of this. Taking benefit of this state, with great intelligence, he employed a strategy which succeeded in creating rift between the disbelievers.37

First, Na‘īm bin Mas‘ūd went to the Banū Quraiẓah, and since he held old relations with them, he met their chieftains and said:

“In my opinion you did not do well in betraying Muḥammad[sa] and joining the Quraish and Ghaṭafān. The Quraish and Ghaṭafān are only here in Madīnah for a few days, but you are permanent residents of this place, because this is your homeland and you shall continue to come into contact with the Muslims. Just remember that when the Quraish, etc. leave from here, they shall not give you the least consideration and shall leave you here at the mercy of the Muslims. In the least, you should demand the Quraish and Ghaṭafān to hand over a few men as hostages, so that you may be reassured that you will not suffer betrayal in the end.”

The chieftains of the Banū Quraiẓah understood this advice of Na‘īm and became prepared to demand hostages from the Quraish so that they would not confront difficulty in the end. After this, Na‘īm bin Mas‘ūd went to the chieftains of the Quraish and said:

“The Banū Quraiẓah are afraid that after you leave they may be faced with difficulty on your account; hence, they are beginning to doubt this alliance and intend to demand a few hostages as a guarantee. However, you should not give them any hostages at all, lest they betray you and hand over your hostages to the Muslims”, etc., etc.

Then, he went to his own tribe, the Ghaṭafān, and said similar things.38 By God’s design, it so happened that the Quraish and Ghaṭafān were already planning an all-out attack upon the Muslims. This attack was to be waged from all four fronts of the city simultaneously, so that the Muslims would not be able to defend themselves due to their meagre number and their line of defence could be penetrated from one place or another. With this intention, they sent word to the Banū Quraiẓah that, “The siege is becoming overly prolonged and people are growing weary. Thus, we have decided that tomorrow all of the tribes shall wage a united attack upon the Muslims, you should also remain prepared for tomorrow’s assault.” The Banū Quraiẓah, who had already spoken with Na‘īm responded, “Tomorrow is our Sabbath day and thus we are unable to engage the following day; and either way, until you hand over to us some hostages as a guarantee that you shall not betray us in the end, we cannot partake in this attack.” When the Quraish and Ghaṭafān received this response from the Banū Quraiẓah, they were left astounded and said, “Na‘īm has spoken the truth, it seems as if the Banū Quraiẓah are bent upon betraying us.” On the other hand, the Banū Quraiẓah received the response of the Quraish and Ghaṭafān that, “We shall not give you any hostages. If you wish to come in support, then do so without any conditions.” As a result, the Banū Quraiẓah said, “It is true that Na‘īm has given us good advice in that the Quraish and Ghaṭafān do not hold good intentions.” In this manner, the intelligent strategy of Na‘īm managed to create rift and dissent within the disbelieving camp.39

This is the strategy which was employed by Na‘īm, but the most remarkable aspect of this was that even in such a sensitive mission, insofar as possible, Na‘īm did not say anything in particular which could be classified as falsehood. As far as the use of tactical strategy is concerned in order to carry out a plan, or to formulate a design by which one may be safeguarded from the mischief of an enemy is concerned, this is not objectionable at all. In fact, it is a very beneficial part of the art of war, by which a cruel enemy can be frustrated and defeated and the unnecessary chain of bloodshed and carnage can be brought to an end.

It was possible that the peaceful efforts of Na‘īm bin Mas‘ūd may have been wasted and after a temporary stumble and shaking, the disbelievers may have regained their unity and steadfastness. However, by God’s design, it so happened that after these occurrences, fierce winds struck at night,40 and as the encampment of the disbelievers was situated in an open plain, this resulted in a fierce storm. Tents were uprooted and their coverings flew off, cooking vessels were overthrown41 and a rain of sand and pebbles began to fill the ears, eyes and noses of the people. Then, more than anything else, the national fires, which were kept alight during the night with great formality according to the ancient Arab custom, began to blow out here and there, like lose debris.42 These spectacles shocked the superstitious hearts of the disbelievers, which were already shaken due to the hardship of this prolonged siege and the bitter experience of mutual distrust among the confederates, that they were unable to regain themselves thereafter. Before dawn, the horizon of Madīnah was cleansed of the dirt and dust of the disbelieving army.

Hence, it so happened that when the storm took on strength, Abū Sufyān summoned the nearby chieftains of the Quraish and said, “Our difficulties are increasing. It is no longer appropriate for us to stay here. It is better for us to return and as for me, I am off.” Upon issuing this command, he ordered his men to retreat and then took to his camel. However, the state of his fear was such that he even forgot to untie the forelegs of his camel. After he had mounted and noticed that the camel was not moving, he remembered that the camel was yet to be untied.43 At this time, Ikramah bin Abū Jahl was standing beside Abū Sufyān, and in somewhat of a bitter tone he said, “Abu Sufyān! You are the commander of the army yet you flee from the army leaving it behind and do not even care for the others.” Abū Sufyān was embarrassed at this and dismounted from his camel saying, “There you are, I am not going anywhere yet, but you should quickly prepare and leave here as quickly as possible.”44 Hence, people quickly became engaged in preparations and shortly thereafter, Abū Sufyān mounted his camel and set off. Until that time, the Banū Ghaṭafān and the other tribes had no knowledge whatsoever of the Quraish’s intent to flee. However, when the encampment of the Quraish began to quickly vacate, the others also found out about this. As a result, the others became fearful as well and announced a retreat.45 The Banū Quraiẓah also retired to their fortresses.46 Along with the Banū Quraiẓah, the chief of the Banū Naḍīr, Ḥuyayy bin Akhṭab also accompanied them to their fortresses.47 Before the light of dawn manifested itself, the entire plain was empty, and by a sudden and astounding transformation of events, the Muslims, who were on the verge of defeat, became triumphant victors.

The very same night, when the disbelievers were fleeing from the field of battle on their own, the Holy Prophet(sa) addressed the Companions around him and said, “Is there anyone from among you who agrees to go and ascertain the state of the disbelieving army at this time?”48 However, the Companions relate that at the time, the cold was so extreme, and then, fear, hunger and exhaustion was so great, that none could find it within themselves to submit a response or make a movement.49 Finally, the Holy Prophet(sa) called out the name of Ḥudhaifah bin Yamān himself, upon which he stood up, shivering in the cold, and presented himself before the Holy Prophet(sa).50 With extreme affection, the Holy Prophet(sa) stroked his head and supplicated in his favour, and said, “Have no fear and rest assured that God-willing, no harm shall come to you.51 Quietly slip into the disbelieving camp and do not create a stir, nor reveal yourself.”52 Ḥudhaifah(ra) relates that:

“When I set off, I noticed that there was no sign of cold in my body. In fact, I felt as if I was passing through a warm room.53 My anxiety left me completely.54 The night was pitch black, and I fearlessly yet silently, penetrated the enemy camp. At the time, I found Abū Sufyān standing above a fire in order to warm himself. Upon seeing him, I immediately took aim with my bow, and was about to shoot, but then I remembered the admonition of the Holy Prophet(sa), and held back from shooting my arrow. If I had shot my arrow, Abū Sufyān was in such close range that most surely, he would not have been able to escape.55 At the time, Abū Sufyān was urging his men to prepare for the return march and then he took to his camel right before my eyes. Due to his anxiety, he forgot to untie the forelegs of his camel. After this, I returned. When I reached my camp, the Holy Prophet(sa) was engaged in Ṣalāt. I waited until the Holy Prophet(sa) had finished and then presented my report of the entire situation. The Holy Prophet(sa) thanked God and said, “This is not the result of our own effort or strength, rather, it is due completely to the Grace of God, Who has put the confederates to flight by His breath.” After this, news of the retreat of the disbelievers immediately spread throughout the Muslim camp.56

It was perhaps on this occasion that the Holy Prophet(sa) also said:

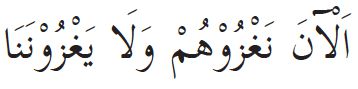

“In the future we shall set out against the Quraish, they shall not have the courage to go forth against us.”57

Hence, after a siege of more or less, twenty days, the army of the disbelievers left Madīnah without success and victory, and the Banū Quraiẓah, who had also come out to aid them retired to their fortress.58 In this war, the Muslims did not suffer a great loss of lives; only five or six men were martyred. Sa‘d bin Mu‘ādh(ra), who was the head-chieftain of the Aus tribe sustained such a heavy wound that in the end, he could not recover. This was a loss for the Muslims which could not be compensated. Only three men from the army of the disbelievers were killed, however, in this battle, the Quraish received such a blow that afterwards, they could never muster the courage to round up a large group and set out like this again, or attack Madīnah. The prophecy of the Holy Prophet(sa) was fulfilled to the letter.

After the army of the disbelievers had set off, the Holy Prophet(sa) also instructed the Companions to return and the Muslims left the field of battle to enter Madīnah. However, the Holy Prophet(sa) had only just reached home, when a state of battle broke out with the Banū Quraiẓah. Unable to rest in Madīnah for even a single night, the Holy Prophet(sa) was compelled to set out from his home to fight them, but the details of this shall be presented ahead.

The battle of the ‘Ditch’ or ‘Confederates,’ which came to an unexpected and sudden end, was a very dangerous war. Until that time, the Muslims had never been faced with a crisis of such magnitude, nor were they ever subjected to such tribulation thereafter in the life of the Holy Prophet(sa). This was a violent quake, which shook the edifice of Islām to its very foundation. Its horrific scenes dazzled the eyes of the Muslims, and their hearts began to reach their throats, and the weaker ones began to think that this was the end. The jolts of this terrible quake shook them for about a month, more or less, and thousands upon thousands of bloodthirsty beasts besieged their homes turning their lives bitter. This bitter affliction was doubled by the treachery of the Banū Quraiẓah, and at the heart of this entire conspiracy were those ungrateful Jews, whom the Holy Prophet(sa) had benevolently permitted to leave Madīnah in peace and security. It was due to the incitement of these very Jewish chieftains, that all of the renowned tribes of the Arabian desert became intoxicated in their animosity for Islām and converged upon Madīnah to expunge the Muslims. It is absolutely certain that on this occasion, if these wild beasts had gained the opportunity to enter the city, not a single Muslim would have survived, and the honour of a single chaste Muslim lady would not have been safe from the filthy attacks of these people. However, it was merely due to the Grace of Allāh the Exalted and the Power of His unseen hand that this swarm of locusts was forced back without success and victory, and the Muslims, who were full of emotions of thankfulness and gratitude, returned to their homes with a breath of peace and satisfaction. The threat posed by the Banū Quraiẓah still existed just as before. These people had secured themselves in their strongholds with peace and security after having displayed their treachery in a most dangerous manner. They now presumed that no one could do them any harm; however, in any case, it was incumbent that their mischief be put to an end. Their presence in Madīnah was no less than a snake in the grass for the Muslims. The experience of the Banū Naḍīr taught that whether this snake was permitted out of its home or left inside, it always proved to be equally lethal.

1 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 33, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

2 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

3 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 625, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

4 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 283, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 35, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

5 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 283, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

6 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 625, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

7 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4113

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 37-38, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

8 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 625-626, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

9 Al-Aḥzāb (33:13)

10 Al-Aḥzāb (33:14)

11 Al-Aḥzāb (33:23)

12 Al-Aḥzāb (33:11-12)

13 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 283, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, pp. 484- 485, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 42-43, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

14 This narration is incorrect, rather, the stated incident relates to the body of Naufal bin ‘Abdullāh, who advanced to murder the Holy Prophet(sa), but fell dead to the ground himself at the hand of Zubair bin Al-‘Awwām(ra). The disbelievers offered to pay the Muslims a sum of 10,000 dirhams in exchange for the body, but the Holy Prophet(sa) refused to accept their money and returned the body for free. Refer to Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 42-43, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul- Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

15 The Life of Mahomet, By Sir William Muir, Chapter XVII, Battle of the Ditch, pp. 231-322, Published by Smith, Elder & Co. London (1878)

16 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4112

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 56-57, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

17 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 59-60, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

18 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 486, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

19 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 627, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

20 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 486, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

21 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 283, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

22 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 627, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

23 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 42, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

24 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 487, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi / Mubārazatu ‘Aliyyin Li-‘Amribni ‘Abdi Wuddin, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 42, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

25 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 627, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

26 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 487, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi / Mubārazatu ‘Aliyyin Li-‘Amribni ‘Abdi Wuddin, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 42, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 627, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

27 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 626-627, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 286, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 40, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

28 Sunanut-Tirmidhī, Kitābuz-Zuhd, Bābu Mā Jā’a Fī Ma‘īshati Aṣḥābin-Nabiyyi(sa), Ḥadīth No. 2371

29 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 485, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

30 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 625, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 483, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

31 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 489, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 629-630, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

32 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 629-630, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

33 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 489, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

34 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 54, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

35 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4115

36 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 55, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

37 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 284, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996) - At this instance, Ibni Hishām has recorded a narration that Na‘īm bin Mas‘ūd presented himself before the Holy Prophet(sa), and then, the Holy Prophet(sa) personally assigned him the task of formulating an intelligent plan by which the disbelievers could be routed. In principle, if this actually happened, there would be nothing objectionable about it, but in light of principles of Riwāyat, this does not prove to be correct. The reason being that firstly, Ibni Hishām has related this account without a chain of narrators, but in comparison to this, Ibni Sa‘d has provided a chain of narrators for the account relayed by him - refer to the aforementioned reference of Ibni Sa‘d. In addition to this, the narration of Ibni Hishām, which has been quoted by Muḥaddith Shirāzī in his work ‘Alqāb’ has been declared a weak narration by research scholars - refer to Al-Jāmi‘uṣ-Ṣaghīru Fī Aḥādīthil-Bashīri Wan-Nadīri, By Jalāluddīn bin Abī Bakr As-Suyūṭī, Volume 2, p. 236, Ḥarful-Khā’i, Ḥadīth No. 3884, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut (2004). Hence, the correct version of this incident seems to be that Na‘īm employed this strategy of his own accord. And Allāh knows best.

38 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 630-631, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

39 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 631, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

40 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 631, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 55, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

41 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 285, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

42 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 55, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 491, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

43 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 632, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 284, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhur-Rusuli Wal-Mulūk (Tārīkhuṭ-Ṭabarī), By Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad bin Jarīr Aṭ-Ṭabarī, Volume 3, p. 105, Thumma Kānatis-Sanatul-Khāmisatu Minal-Hijrati / Dhikrul-Khabari ‘An Ghazwatil-Khandaqi, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon, Second Edition (2002)

44 As-Sīratul-Ḥalabiyyah (Insānul-‘Uyūni Fī Sīratil-Amīni Wal-Ma’mūn), By ‘Allāmah Abul-Farj Nūruddīn ‘Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Aḥmad Al-Ḥalabiyy, Volume 2, p. 436, Bābu Dhikru Maghāzīhi(sa) / Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2002)

45 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 632, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

46 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 492, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

47 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 634, Ghazwatu Banī Quraiẓatah Fī Sanati Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

48 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābul-Jihād Was-Siyar, Bābu Ghazwatil-Aḥzāb, Ḥadīth No. 4640

49 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 632, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Tārīkhur-Rusuli Wal-Mulūk (Tārīkhuṭ-Ṭabarī), By Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad bin Jarīr Aṭ-Ṭabarī, Volume 3, p. 104, Thumma Kānatis-Sanatul-Khāmisatu Minal-Hijrati / Dhikrul-Khabari ‘An Ghazwatil-Khandaqi, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon, Second Edition (2002)

50 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābul-Jihād Was-Siyar, Bābu Ghazwatil-Aḥzāb, Ḥadīth No. 4640

51 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 49, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 491, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

52 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 632, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

53 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābul-Jihād Was-Siyar, Bābu Ghazwatil-Aḥzāb, Ḥadīth No. 4640

54 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 49, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

55 Ṣaḥīḥu Muslim, Kitābul-Jihād Was-Siyar, Bābu Ghazwatil-Aḥzāb, Ḥadīth No. 4640

56 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 632, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Tārīkhur-Rusuli Wal-Mulūk (Tārīkhuṭ-Ṭabarī), By Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad bin Jarīr Aṭ-Ṭabarī, Volume 3, p. 105, Thumma Kānatis-Sanatul-Khāmisatu Minal-Hijrati / Dhikrul-Khabari ‘An Ghazwatil-Khandaqi, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon, Second Edition (2002)

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 53, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

57 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4110

58 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 484/ p. 491-492, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut