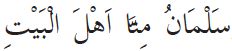

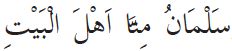

, i.e., ‘Salmān is to be counted from amongst the members of my family.’”20 From then on, Salmān received the honour of being known as a family member of the Holy Prophet(sa).

, i.e., ‘Salmān is to be counted from amongst the members of my family.’”20 From then on, Salmān received the honour of being known as a family member of the Holy Prophet(sa).Now we enter that period of Islāmic history, when the animosity of the Arabian tribes against Islām not only reached its heights, rather, they gathered their strength and firmly resolved to uproot Islām with a unified plan. However, divine power was manifested in such a manner that this very unity bore the seed of failure. This edifice was still being constructed when its foundations became hollow and began to crumble. The details are that although the Quraish of Makkah and the tribes of Najd known as the Ghaṭafān and Sulaim, were already thirsty for Muslim blood and remained forever engaged in schemes to attack Madīnah, until now they had not yet collected their forces in a single field to oppose Islām. When the people of Banū Naḍīr, which was a Jewish tribe, were exiled from Madīnah due to their treachery and sedition, their chieftains forgot this noble, nay, benevolent treatment of the Holy Prophet(sa) and proposed among themselves to collect the dispersed forces of the whole of Arabia at one place in an attempt to expunge Islām.1 Since the Jewish people were very clever and cunning, and possessed great mastery in hatching such conspiracies, their seditious efforts proved to be successful; the tribes of Arabia came together in the field of battle as one against the Muslims.

Among the Jewish chieftains, Salām bin Abil-Ḥuqaiq, Ḥuyayy bin Akhṭab and Kinānah bin Ar-Rabī‘ were primarily responsible for this uprising.2 These mischief-makers set out from their new homeland of Khaibar and toured the tribes of Ḥijāz and Najd, but before anything else, they reached Makkah and brought the Quraish onboard.3 In order to please the Quraish, they even said that their religion (polytheism and idol worship) was better than the religion of the Muslims.4 Then, they travelled to Najd and allied with the Ghaṭafān tribe5 and prepared the branches of this tribe such as the Fazārah, Murrah and Ashja‘, etc., to go forth with them.6 After this, due to the incitement of the Quraish and Ghaṭafān, the tribes of Banū Sulaim and Banū Asad also joined this chain of unity in opposition of Islām.7 Along with this, the Jews sent word to their ally the Banū Sa‘d, and incited them to stand in aid of them.8 In addition to this strong coalition, the Quraish brought aboard many people from among the surrounding tribes who were subservient to them.9 Finally, after full preparation, these bloodthirsty beasts of the Arabian desert overflowed into Madīnah in the likeness of a grand flood with the intention of annihilating the Muslims. They resolved that until they had expunged the Muslims from the face of the earth, they would not return.

This grand army of the disbelievers is estimated to have been from between 10,00010 to 15,000 men;11 rather, in light of certain narrations, 24,000 men.12 Even if the estimate of 10,000 is taken as correct, at that time, this number was so great that perhaps prior to this, such a large number had never taken part in the tribal wars of Arabia. The arrangement was such that the overall leader or commander in chief of the entire army was Abū Sufyān bin Ḥarb,13 who also lead the individual contingent of the Quraish as well.14 The tribes of Ghaṭafān were collectively lead by ‘Uyainah bin Ḥiṣn Fazārī, and under him, there was a separate commander for each tribe. The commander of the Banū Sulaim was ‘Abdi Sufyān Shams, while the Banū Asad were lead by Ṭulaiḥah bin Khuwailid.15 Food and drink, as well as equipment of war was ample in all respects. This army began to march towards Madīnah in Shawwāl 5 A.H., i.e., February or March 627 A.D.16

It was difficult for such a big army to keep its movements secret, and then, the intelligence system of the Holy Prophet(sa) was also very well organised. Hence, the army of the Quraish had only just left Makkah when the Holy Prophet(sa) received news, upon which he gathered the Companions and sought counsel in this regard. In this consultative meeting, a sincere Companion from Iran named Salmān(ra), the Persian, was also present. His acceptance of Islām has already been alluded to above. Since Salmān(ra), the Persian, was knowledgeable in non-Arab strategy of war, he proposed that a long and wide ditch be dug around that part of Madīnah, which was insecure, in order to defend themselves. The idea of a ditch was a novel concept for the Arabs, but upon learning that this method of war was generally prevalent among the non-Arab world, the Holy Prophet(sa) accepted this proposal.17 The city of Madīnah was secure on three fronts to some extent. Due to the walls of a continuous succession of homes, thick trees and large rocks, these fronts were protected from a sudden attack by the army of the Quraish. It was only from the front facing towards Syria that the enemy could swarm upon Madina. For this reason, the Holy Prophet(sa) instructed that a ditch be dug along the unprotected side of Madīnah.18 Under his own supervision, the Holy Prophet(sa) had the lines of the ditch marked out and divided the ditch into segments of fifteen feet each, after which he divided this work amongst groups of ten Companions.19

In the division of these parties, a friendly debate arose as to which group Salmān(ra), the Persian, would be counted amongst. Would he be counted amongst the Muhājirīn, or due to his having arrived in Madīnah prior to the advent of Islām, would he be considered a part of the Anṣār? Since Salmān(ra) was the originator of this idea and despite being of old age, was an active and strong man, both groups desired to include him among themselves. Eventually, this disagreement was presented before the Holy Prophet(sa). Upon hearing the arguments of both parties, he smiled and said, “Salmān is from neither one of these parties, rather,  , i.e., ‘Salmān is to be counted from amongst the members of my family.’”20 From then on, Salmān received the honour of being known as a family member of the Holy Prophet(sa).

, i.e., ‘Salmān is to be counted from amongst the members of my family.’”20 From then on, Salmān received the honour of being known as a family member of the Holy Prophet(sa).

Hence, after the plan of digging a ditch had been finalised, the Companions came into the field of battle dressed as labourers. The work of excavation was not an easy task, and then, the cold season was also in full force, due to which the Companions were made to bear severe hardships. Moreover, since all other business came to a halt, those people who earned their bread and butter on a daily basis, and there were many such people from among the Companions, were compelled to bear the adversity of hunger and starvation as well. Furthermore, since the Companions did not have servants and slaves, all of them had to work with their own hands.21

Within these parties of ten, there was a further division of work, where certain men would dig and others would fill this excavated earth and stones in baskets carried on their shoulders and throw it away. The Holy Prophet(sa) would spend most of his time near the ditch and would often join the Companions in digging and transporting the dirt. In order to keep their spirits high, on certain occasions, during the course of work, the Holy Prophet(sa) would begin to recite couplets, upon which the Companions would sing along the same verse with the Holy Prophet(sa). The following couplet recited by the Holy Prophet(sa) has been especially recorded in narrations:

“O Our Lord! True life is that of the hereafter. Make it so by Your Grace, that the Anṣār and Muhājirīn are blessed with your forgiveness and bounty in the life of the hereafter.”22

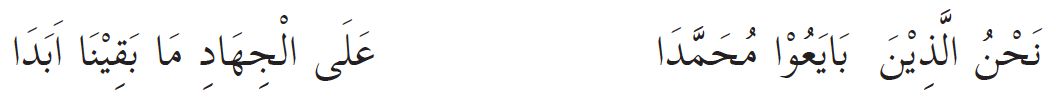

In response to this couplet, on certain occasions, the Companions would recite the following verse:

“We are those who have taken oath on the hand of Muḥammad(sa), that we shall continue to strive in Jihād until the breath of life remains within us.”23

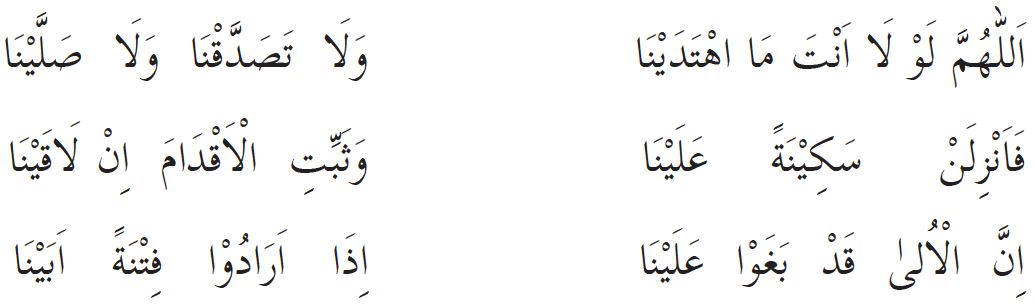

At times, the Holy Prophet(sa) and his Companions would recite the following verses of ‘Abdullāh bin Rawāḥah:

“O Our Lord! Had it not been for Your Grace, we would not have been guided, nor would we have been able to give charity and alms, and worship You. O God! When You have brought us this far, grant our hearts tranquility in this time of adversity. If we face the enemy, make our steps firm. You are aware that these people have stood up against us in a manner of tyranny and oppression, and their purpose is to turn us away from our faith. But O Our God! By Your Grace, our state is such that when they devise a plan to turn us away from our faith, we repel their design from afar, and refuse to fall victim to their disorder.”24

When the Holy Prophet(sa) would reach the final couplet, he would raise his voice loudly. It is narrated by a Companion that he saw the Holy Prophet(sa) reciting these verses in such a state that his blessed body was completely covered with dirt, due to his transporting soil.25 This was a time of hunger and starvation; and what to talk of the Companions, even the Chief of the Universe (peace and blessings of Allāh be upon him) would starve on many occasions. In order to cope with this pain, the Holy Prophet(sa) would move about with a stone tied to his stomach.26

In this very state of adversity and difficulty, while the ditch was being dug, a stone which simply refused to break was excavated. The state of the Companions was that due to three days of continuous starvation, they fell faint. Unable to succeed in this task, they finally presented themselves before the Holy Prophet(sa) and submitted, “There is one stone which knows no breaking.” At the time, the Holy Prophet(sa) had also tied a stone on his stomach due to hunger, but he immediately went there upon their request and lifting an axe, struck the stone, in the name of Allāh.27 When iron hit stone, a spark flew, upon which the Holy Prophet(sa) loudly said, “God is the Greatest!” Then he said, “I have been granted the keys of the kingdom of Syria. By God, at this time, I am beholding the red-stone palaces of Syria.” His stroke had somewhat crushed a portion of the stone. The Holy Prophet(sa) wielded the axe a second time in the name of Allāh, which caused a spark again, upon which the Holy Prophet(sa) said, “God is the Greatest!” Then he said, “This time, I have been granted the keys of Persia, and I am witnessing the white palaces of Madaen.” Now, the rock had been broken to a large degree. The Holy Prophet(sa) wielded the axe yet a third time, which resulted in another spark and the Holy Prophet(sa) said, “God is the Greatest!” Then he said, “Now, I have been endowed the keys of Yemen, and by God, I am being shown the gates of San‘a at this time.” Finally, the rock was broken completely. In another narration it is related that on every occasion, the Holy Prophet(sa) would loudly proclaim the Greatness of God and after the Companions would inquire, he would relate his visions.28 After this temporary hindrance had been removed, the Companions engaged in their work once again. These were visions of the Holy Prophet(sa). In other words, during this time of affliction, Allāh the Exalted created a spirit of hope and delight amongst the Companions by showing the Holy Prophet(sa) visions of the future victories and prosperity of the Muslims. However, apparently at the time, the circumstances were of such difficulty and hardship that upon hearing these promises, the hypocrites of Madīnah mocked the Muslims saying, “They do not even possess the strength to step out of their own homes and are dreaming of the kingdoms of Caesar and Chosroes.”29 However, in the estimation of God, all of these bounties had been decreed for the Muslims. Therefore, these promises were fulfilled at their respective times. Some were fulfilled in the last days of the Holy Prophet(sa), while most were fulfilled in the era of his Khulafā’, and thus, became a source of increasing the Muslims in faith and gratitude.

On this very occasion, a faithful Companion of the Holy Prophet(sa) named Jābir bin ‘Abdullāh(ra) noticed signs of weakness and starvation on the countenance of the Holy Prophet(sa), and sought permission to go home for a short while. Upon arriving at home, Jābir(ra) said to his wife, “It seems as if the Holy Prophet(sa) is in great hardship due to extreme hunger. Do you have something to eat?” She responded, “Yes, I have some barley flour and one goat.” Jābir(ra) states, “I slaughtered the goat and kneaded the flour into dough. Then, I said to my wife, ‘You prepare the food, while I present myself before the Holy Prophet(sa) and request him to come over.’” My wife said, “Look here, do not embarrass me. The food is very little. Do not bring too many people along with the Holy Prophet(sa).” Jābir(ra) goes on to relate, “I went and almost in a whisper submitted to the Holy Prophet, ‘O Messenger of Allāh! I have some meat and barley dough and have asked my wife to prepare the food. I would request you to come over with a few Companions and eat at our home.’” The Holy Prophet(sa) said, “How much food do you have?” I submitted that we have such and such amount. The Holy Prophet(sa) said, “It is plenty.” Then, the Holy Prophet(sa) cast a glance around him and called out in a loud voice, “O company of the Anṣār and Muhājirīn! Come along. Jābir has invited us to a meal. Let us go and eat.” At this voice, about 1,000 hunger-stricken Companions joined the Holy Prophet(sa). The Holy Prophet(sa) instructed Jābir(ra), “Go home quickly and tell your wife that until I arrive, she should not take the cooking pot off the stove, nor should she begin to prepare the bread.” Jābir hurried home at once and informed his wife. The poor lady became extremely worried, because the food was only enough for a few, and since a multitude of people were on their way, she had no idea what to do. However, when the Holy Prophet(sa) arrived, he very calmly prayed and said, “Now begin baking the bread.” After this, the Holy Prophet(sa) began to slowly distribute the food. Jābir(ra) relates, “I swear by that Being, in Whose hand is my life, that this food sufficed for everyone and all ate their fill. Our pot was still boiling and the dough had not been used up completely.”30

1 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

2 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 621, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

3 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 621, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhisa Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

4 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, pp. 621-622, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

5 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 622, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

6 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 622, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

7 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 480, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

8 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 480, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

9 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

10 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 624, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

11 Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 23, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

12 Fatḥul-Bārī referenced by Sīratun-Nabī

Mir‘ātul-Mafātīḥ, By Abul-Ḥasan ‘Ubaidullah bin Muḥammad ‘Abdis-Salām, Volume 2, p. 71, Kitābuṣ-Ṣalāh, Bābu Faḍā’iliṣ-Ṣalāh, Al-Faṣlul-Awwal, Ḥadīth No. 634, Al-Maktabatul-Athriyyatu, Sangla Hill [Publishers]

13 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

14 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 622, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

15 Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

16 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 621, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

17 Tārīkhur-Rusuli Wal-Mulūk (Tārīkhuṭ-Ṭabarī), By Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad bin Jarīr Aṭ-Ṭabarī, Volume 3, p. 97, Thumma Kānatis-Sanatul-Khāmisatu Minal-Hijrati / Dhikrul-Khabari ‘An Ghazwatil-Khandaqi, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon, Second Edition (2002)

Aṭ-Ṭabaqātul-Kubrā, By Muḥammad bin Sa‘d, Volume 2, p. 282, Ghazwatu Rasūlillāhi(sa) Al-Khandaqa Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dāru Iḥyā’it-Turāthil-‘Arabī, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

Ar-Rauḍul-Unufi Fī Tafsīris-Sīratin-Nabawiyyati libni Hishām, By Abul-Qāsim ‘Abdur-Raḥmān bin ‘Abdillah bin Aḥmad, Volume 3, p. 416, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul- Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition

18 Tārīkhul-Khamīs Fī Aḥwāli Anfasi Nafīs, By Ḥusain bin Muḥammad bin Ḥasan, Volume 1, p. 481, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi, Mu’assasatu Sha‘bān, Beirut

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, p. 17, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

19 Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 7, p. 505, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4102, Qadīmī Kutub Khānah, Ārām Bāgh, Karachi

20 Tārīkhur-Rusuli Wal-Mulūk (Tārīkhuṭ-Ṭabarī), By Abū Ja‘far Muḥammad bin Jarīr Aṭ-Ṭabarī, Volume 3, p. 98, Thumma Kānatis-Sanatul-Khāmisatu Minal-Hijrati / Dhikrul-Khabari ‘An Ghazwatil-Khandaqi, Dārul-Fikr, Beirut, Lebanon, Second Edition (2002)

21 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4099

22 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4099

23 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4099

24 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4104

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4106

25 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4106

Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Jihād Was-Siyar, Bābu Ḥafril-Khandaqi, Ḥadīth No. 2837

26 It was a custom among the Arabs that in a time of hunger or extreme difficulty, when nothing was available to eat, they would tie a stone or Ḥajar, on their stomach, by which slouching could be prevented and the body could be tightly held in an upright position. It is due to this very custom that the Urdu proverb came about that, ‘So and so walks about with a stone tied to his stomach.’ It is also possible that the word Ḥajar refers to a piece of cloth tied around the waist, because in the Arabic language, the word Ḥajar also refers to a cloth. Refer to Majma‘ul-Biḥār. Allāh knows best.

27 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4101

28 Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 7, p. 505, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4102, Qadīmī Kutub Khānah, Ārām Bāgh, Karachi

Sharḥul-‘Allāmatiz-Zarqānī ‘Alal-Mawāhibil-Ladunniyyah, By Allāmah Shihābuddīn Al-Qusṭalānī, Volume 3, pp. 31-33, Ghazwatul-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (1996)

29 As-Sīratun-Nabawiyyah, By Abū Muḥammad ‘Abdul-Mālik bin Hishām, p. 626, Ghazwatul- Khandaqi Fī Shawwālin Sanata Khamsin, Dārul-Kutubil-‘Ilmiyyah, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition (2001)

30 Ṣaḥīḥul-Bukhārī, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4101

Fatḥul-Bārī Sharḥu Ṣaḥīḥil-Bukhārī, By Al-Imām Aḥmad bin Ḥajar Al-‘Asqalānī, Volume 7, p. 505- 507, Kitābul-Maghāzī, Bābu Ghazwatil-Khandaqi Wa Hiyal-Aḥzābu, Ḥadīth No. 4102, Qadīmī Kutub Khānah, Ārām Bāgh, Karachi