The second object of religion set out above is in fact a corollary of the first. A man who attains to a complete realization of God would naturally eschew immoralities and evils of all kinds and, conversely, the more a man is involved in vice the farther away from God he drifts. The Holy Quran says, ‘Those who sin in ignorance,’1 meaning that the real cause of sin is lack of true knowledge and realization of God, which is a self-evident truth. A sensible man will not knowingly thrust his hand into fire; he will not eat food which to his knowledge contains poison; he will not enter a house which he is certain is about to fall; he will not thrust his hand into the hole of a serpent; nor will he enter the den of a lion unarmed. Men being so much afraid of fire, poison, serpents, and lions, how can it be supposed that they would rush into and revel in vices and immoralities if they had a perfect realization of God and knew that these things were more deadly than poisons and more dangerous than serpents and lions? It is, therefore, clear that sin is the result of ignorance and lack of true realization of God, and that a religion which leads to certainty of faith and true realization of God will necessarily perfect the morals of its followers. But as the subject is in itself a vital and interesting one, and most people cannot derive any great benefit from mere inferences but stand in need of detailed exposition, I shall briefly set out the teachings of Islam concerning this object of religion.

In dealing with the first object of religion I had pointed out that the fact that all religions agreed in giving some name or other to the attributes of God had no significance at all, and that our attention should rather be directed to the details and explanations furnished by each religion concerning such attributes; for it could never be that a religion should openly ascribe some defect or shortcoming to God. Therefore a comparison between different religions was possible only if we tried to discover the details of their teachings concerning the attributes of God. If these details did not correspond with the true attributes of God, a religion could not claim that it acknowledged these attributes, nor could we conclude that that religion shared with other religions a common conception of God. If a man calls water milk, that will not make water milk; nor will any sensible person be deceived by the mere name in the absence of the qualities of milk in water. The same is the case with the moral teachings of different religions. In instituting a comparison between these teachings we can pay but little regard to general moral injunctions, for no religion is likely to teach its followers to try to win the pleasure of God by, for instance, a course of lies, thefts, robberies, oppression, breaches of trust, abuse, vituperation, quarrels, strife, disorder, etc. Nor can we imagine that a religion would exhort its followers not to speak the truth, or not to act with kindness or affection, or to commit breaches of trust, or to dislike progress and reform, or to discard nobility, dignity, self-respect and meekness, or to suppress all feelings of beneficence and gratitude. A religion which aspires after universal acceptance and respect, is bound to provide a code of moral teachings, that code being common to all religions. If it fails in this respect human nature is sure to revolt against it, and thus it would be doomed to swift disappearance.

Such general moral injunctions, therefore, do not help us much. They are common to all religions, and no religion can pride itself on its exclusive proprietorship of them, nor can we derive any intellectual benefit from this sameness of moral teachings, for it is the result of compulsion and not of any deep insight or research into the sources and working of human nature and conduct. I am often amused by the attempts of people who seek to establish the superiority of their respective religions and to propagate their faiths by first putting together all the general moral injunctions and then representing them as their own exclusive teachings. Whereas the fact is that these injunctions are not peculiar to any religion; they are common to the most ancient, the most primitive as well as the latest and, if I may say so, the most advanced religions. Even the peoples or tribes that are reckoned among savages and have very crude ideas about religion would, if we disregard their actions, and question them calmly and kindly about morals, tell us something very closely resembling that which is taught by more advanced religions. It is, therefore, absurd to base the truth of one’s religion on factors which are the property even of savages. In comparing the moral teachings of different religions, therefore, we must have regard to the details and explanations of moral qualities, their sources and the means of acquiring them, and the sources of evil conduct and the means of avoiding it, etc.

I desire at the outset to point out that there is a great deal of misapprehension and misunderstanding concerning the true conception of morals and moral qualities. This too operates as an obstacle in the way of instituting an accurate comparison between the teachings of different religions. There is a general notion that love, forgiveness, courage, etc., are good moral qualities, and that anger, hate, severity, fear, etc., are undesirable qualities. This is an entirely erroneous conception, for all these are natural instincts and are neither good nor bad in themselves. Neither are love, forgiveness and courage; nor anger, hate, severity and fear, moral qualities. They are merely the natural instincts of man—nay, even of animals. We find them among animals also, for they too love and forgive, exhibit courage, anger, fear and hate. But has any one ever said that a sheep or a cow or a horse possesses high morals? What we call high moral qualities in man are called instincts in animals. Why should this be so? Why is it that those things which are described as high morals in man are not given that name when found in the lower animals? The reason is obvious. We know that these natural instincts or tendencies are not in themselves good or bad morals, and that it is something else in man the operation of which turns them into moral qualities.

We must, therefore, search for that something else in man, which converts natural tendencies into moral qualities. That something else is supplied by the operation of reason and good sense. Natural tendencies when governed and regulated by reason and good sense become moral qualities, and as every man is presumed to regulate his conduct by reason and good sense, these being the qualities which distinguish man from other animals, man’s conduct is termed moral, although, as a matter of fact, in many instances it may only be the result of a natural instinct or tendency. Some people, for instance, are so forbearing by nature that they never object to anything, and some are so determined that they never relinquish a project which they have once taken in hand. Neither of these classes of persons can be described as possessing high moral qualities, for their acts and omissions are not governed by reason or intention but are almost involuntary, just as the fact that a dumb person refrains from abusing others or that a maimed person refrains from causing hurt to others, is not a moral quality, but the result of a physical disability. In short, the proper use, and not merely the use, of natural instincts and tendencies is a moral quality.

Having cleared the ground so far, we can easily understand that a religion which teaches us merely to be kind, or forgiving or affectionate or brave, does not teach us good morals, but merely enumerates our natural tendencies. Are not all these qualities to be found in animals? Are not animals kind and brave? Do they not love and forgive and show sympathy? We very often see that an animal approaches another animal which happens to have been injured, stays near it, and looks at it affectionately so as clearly to convey the impression that it is expressing its sympathy with the other. Again; we sometimes see animals licking each other in affection. Instances may be multiplied to show that all these instincts are to be found in them. Such teachings, therefore, amount to no more than directions that we should obey our natural instincts, and have no greater moral value than injunctions to the effect that we should eat when we are hungry and should drink when we are thirsty and should sleep when we feel fatigued and worn out. Surely, we do not stand in need of religion to tell us all this. Our nature is a sufficient guide in these matters. A religion which merely repeats these things proves its own futility, for this means that it is not aware of the true conception of morals.

Can any one point out a country where the people do not love, or sympathize with one another in distress, or forgive the faults of others, or are not charitable to the poor? Or, is there a single individual in existence, who does not exhibit most of these qualities? Then, how does a religion improve matters by telling us to do these things?

If, however, by telling us that we should be kind, forgiving, brave, etc., a religion means that we should never exercise severity, or inflict punishment, or exhibit fear, it may have a claim to novelty, but its teachings would be unnatural. We are, by nature, endowed with these qualities, and it is impossible for us to renounce them, nor can a renunciation of them improve our morals, for all that nature has bestowed on us is for our good, and its total suppression or renunciation is more likely to injure our morals than to improve them. For instance, if we are told always to be kind and never to be severe, it would mean that teachers should never admonish their pupils, parents should never rebuke their children, and a Government should never punish those who rebel against it. Again, if we are taught never to be influenced by fear, it would mean that we must always persist in a course of conduct which we have once adopted, even if our error has become manifest to us, and should pay no heed to consequences and should not be afraid of incurring any loss or damage, whether relating to our temporal affairs or to our faith or belief. Can any reasonable person describe these as instances of good moral qualities? Morals mean the use of natural instincts and tendencies befitting the occasion, and not their use on all occasions regardless of their propriety or impropriety. On the other hand, the total suppression of these tendencies is both unnatural and harmful. Only that religion, therefore, can be said to have realized the philosophy of human conduct and morals, and to have given correct directions with regard to them, which clearly grasps the distinction pointed out above and lays down rules of conduct with reference to it and does not merely enumerate our natural instincts.

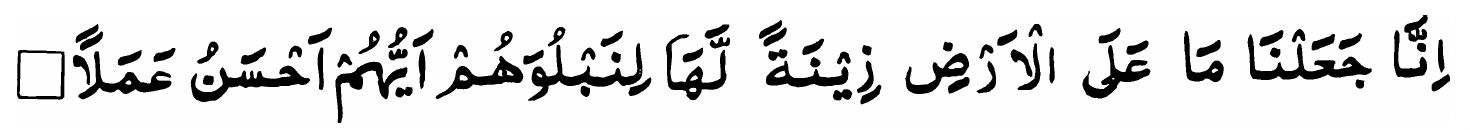

So far as my knowledge extends, Islam alone, of all religions, has kept this distinction in view and has laid down correct rules of conduct. For instance, the Holy Quran says:

‘The recompense of evil should be in proportion thereto; but if a man forgives a trespasser, under circumstances which are calculated to effect a reformation in his conduct and which do not lead to disorder or disturbance, his reward is with God. Verily He loves not the transgressors.’2

A man who inflicts punishment severer than that warranted by the offence, or punishes an offender merely out of revenge in a case where he knows that punishment would harden him and injure his morals still further, or forgives an offender knowing that if he is not punished he will become more daring and embark upon a fresh career of wrong-doing, is a ‘transgressor’ within the meaning of the above verse, and God will not approve of his conduct.

Let us consider the true significance of the rule laid down in this verse. The rule laid down with reference to the natural instincts of man is that an offender should be punished in proportion to his offence. But it is pointed out that high morals demand that in meting out punishment a man should consider whether the wrong-doer would be reformed by punishment or by forgiveness. If there is hope of reforming him by forgiveness, he should be forgiven and should not be punished merely out of revenge for the wrong done by him. If on the other hand, punishment would prove more salutary than forgiveness, then he should be punished, and not forgiven out of mere squeamishness, for, otherwise, he would be deprived of a chance of reforming himself, and it would be cruel and not merciful to forgive in such a case. A person, therefore, who realizes that forgiveness or punishment would be more effective in reforming a wrong-doer, and yet adopts a contrary course, is guilty of cruelty in the sight of God, even if he has forgiven, for forgiveness, in such a case, amounts to intentional injury to another person’s morals.

The Holy Prophet (sas) has expressed the same thing in other words. He says, ‘Human actions are those that are the result of intention.’3

An act done under the influence of a natural instinct or passion cannot be called a human or a moral act; it is the working of an animal instinct or passion. A horse or a donkey, under the circumstances, would have acted in the same manner. A human or a moral act must be the result of deliberation and design.

This would show that Islam has realized the true significance of morals and has prescribed rules of conduct in accordance with it. Therefore, only those religions can be compared with it whose moral teachings are based on the same conception of morals. To call a mere enumeration of natural instincts a code of moral teachings would be doing violence to language.

Islam thus defines good morals as the proper use of natural instincts under the guidance of reason and judgment. It condemns as bad morals their improper use which does not take into consideration the propriety or otherwise of a particular action on a particular occasion. I shall now proceed to give instances of rules of moral conduct laid down by Islam, which illustrate the restrictions placed by Islam on the exercise and working of natural instincts so as to render them of the utmost possible benefit to man.

Islam classifies morals as being of two kinds, those relating to the mind and those relating to the body. This classification considerably exalts the moral conception. The Holy Quran says:—

‘Go not near evils, manifest or hidden.’4

In other words, a Muslim is forbidden to approach not merely those evils which become, or can become, known to others, but also those that are committed by the mind and cannot become known to others, except when confessed by the offender himself. Again, it says:

‘Whether you make that manifest which is in your minds (that is to say, whether you act in accordance with it) or whether you keep it secret (that is to say, whether you confine it to your mind and do not translate it into action), God will call you to account for it.’5

These morals are further subdivided by Islam into good morals and bad morals. For instance, the Holy Quran says, ‘Morals are of two kinds, good and bad; and good morals prevail against bad morals.’6 In other words, a man who adopts good morals gradually subdues his bad morals.

Good and bad morals are again subdivided into two classes, those that affect the individual alone, and those that are likely to affect others also.

These classifications would show that Islam assigns to morals a much more extensive scope than is done by other religions. It does not confine the conception of morals to acts or omissions which affect others, but also includes within this conception acts or omissions which affect the individual himself alone. The Holy Quran refers to this principle in the following verse:

‘O believers, look after the welfare of your souls, and discharge the spiritual obligations that you owe them. If the salvation of another is regarded as possible by your forsaking the path of rectitude and virtue nevertheless adhere to virtue, for, if another goes astray because you have been rightly guided and have adopted virtue, God will not, on that account, be offended with you, and expect you to save another by destroying yourselves.’7

The Holy Prophet (sas) says, ‘Thyself has claims on thee,’8 that is to say, you are not merely to look after others; you must also regard the welfare of your own self, and provide means for its physical and spiritual development. According to Islam, that which is hidden is as much moral or immoral as that which is manifest. So that not only is a man who is openly arrogant, immoral, but a man who is outwardly meek and humble but nurses pride in the secret corners of his heart is equally immoral, for, although he has not injured another, he has injured and sullied his own soul. As the Holy Quran says:

‘They were presumptuous in their hearts and were also very overbearing.’9

Again, a man who entertains evil suspicions concerning another, is guilty of immorality, although he does not publish such suspicions, as the Holy Quran says, ‘Some thoughts of the mind are sinful’ (i.e., those that are the outcome of evil suspicions).10

Similarly, oppressive, disorderly and dishonest designs are immoral according to Islam although the person who entertains them is unable to carry them out owing to lack of courage or lack of means. Such a person does not deserve to be called good, merely on the basis of such of his actions as can be seen.

Conversely, a man who has the good of humanity at heart and is anxious to serve his fellow-beings and to promote their welfare, is according to Islam a good man, although he may be unable to translate his thoughts and wishes into action owing to lack of means or opportunities for such service.

There is, however, an exception to this general rule. A man who is assailed by evil thoughts,—for instance, by pride, jealousy, hate or evil suspicions, but who suppresses them, is not guilty of an immorality, for such a man really combats evil and deserves commendation. Conversely, a man who experiences a sudden rush of good thoughts or a sudden inclination towards doing good, but does not encourage such thoughts or inclination, does not deserve to be called a good man on that account, for, as has already been said, good or bad morals are the result of deliberation and design, and in these two instances good and evil thoughts were not the result of deliberation, but were, as it were, involuntary. The Holy Quran illustrates this principle in the verse:

‘God will call you to account for those thoughts that are the result of deliberation,’11 and not for those that are accidental and are driven out as soon as discovered.

The Holy Prophet (sas) explains this by saying:

‘If a man is assailed by an evil thought but he suppresses it or drives it out of his mind and does not act in accordance with it, God will bestow upon him a good recompense for having so acted.’12

This exception which relates to such morals as concern the individual himself, is also applicable to morals which affect others. As God says:

‘God will recompense those people with good who avoid evil of all kinds, whether great or small, and when they are about to commit evil under a sudden urge, check themselves and turn away from it.’13

That is to say, if a man, owing to carelessness or under the influence of sudden passion, is about to stumble into evil, but as soon as he perceives what he is about to do, checks himself and pilots himself to safety, he will not be counted a bad or immoral man. On the contrary, his conduct will deserve praise, for he is like a man fighting in the defence of his country though he has not yet attained complete victory.

I shall next illustrate the teachings of Islam concerning morals by reference to specific moral qualities. This subject is so vast that to deal with it in any detail one would require much larger space than I can here afford. I shall, therefore, confine myself to the discussion of only a few moral qualities by way of illustration. In doing so, I shall keep in view the classification which I have indicated above in defining morals, viz., that morals consist in the proper use of natural instincts.

I shall first deal with the natural instincts of pity and revenge. Man, in common with other animals, possesses the natural instinct under which he tries to avoid inflicting pain on others, and the sorrows and misfortunes of others affect his mind in such a manner that he begins to share in their troubles. All persons would feel drawn towards a sick person and would have sympathy for him; except perhaps those who are too busy to pay him any attention or those who may have suffered at his hands. The latter, very likely, instead of feeling any sympathy for the afflicted person, may actually enjoy the sight of his suffering. This last feeling is called Naqam, or vengeance and is a distinct feeling which comes into operation when a man suffers pain or loss at the hands of another and wishes to inflict pain or loss on him in return. In a case like this the feeling of revenge displaces the feeling of pity or compassion; and the person who inflicts pain, instead of pitying the man on whom pain is inflicted, derives a distinct pleasure from his suffering. The feeling of revenge, unless controlled by law, assumes several forms. Some times the person aggrieved is able, or imagines that he is able, to inflict pain on the aggressor, and he proceeds to inflict, or attempts to inflict, on the latter such pain as the latter had caused to him, his object being that the latter should suffer as he had himself suffered. In other cases, the aggressor or his family or tribe may happen to be more powerful than the aggrieved person, or the latter may imagine that a repayment in kind would not be approved by others, or owing to some other reason he may be unable or unwilling to inflict real pain on the aggressor, so he uses the weapon of invective or backbiting against him. It might happen that the aggressor is so powerful that the aggrieved person cannot even use his tongue against him. In such a case, he may discontinue visiting him and put an end to all intercourse with him. In some cases even this may not be possible and then the aggrieved person may merely entertain spite against the aggressor, and take pleasure in the misfortunes and sufferings of the latter and be displeased at his success and good fortune.

The natural instinct of vengeance thus manifests itself in many forms, and incites a person to a variety of acts. To put a restraint upon the working of this instinct and to place it under the control of reason is called moral, and to permit it to work unrestrained and uncontrolled by reason would be immoral.

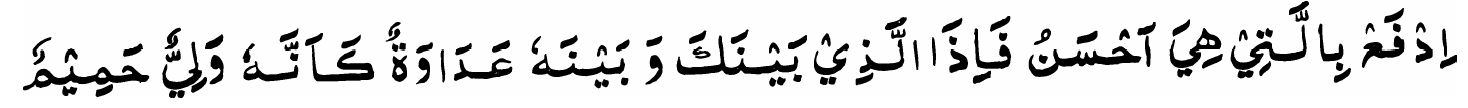

Islam defines the restraints to be placed upon the working of this instinct, which are necessary to convert it into a moral quality, in the following verse:

‘If a man commit a trespass against you, you may inflict upon him punishment proportionate thereto.’14

This is the general rule and regulates the conduct of those whose reason and judgment are not sufficiently developed to appreciate the niceties of moral rules of conduct. For those whose reason and judgment have been better developed a further restriction is placed in the verse:

‘The reward of those who forgive the trespass of others, intending thereby to effect a reformation, is with God. God loves not the transgressors.’15

A person who forgives, when forgiveness would promote disorder, and one who punishes when punishment would harden the offender, are both transgressors, and God loves not such conduct. In other words, a restriction is placed on the exercise of the feeling of pity, which leads to forgiveness, and of revenge, which leads to punishment. It is laid down that when forgiveness is more likely to produce a good impression on the offender and to save him from further wrong-doing, pity ought to be allowed to have its course and he should be forgiven. But when punishment is expected to have a more deterrent and reformative effect on the offender, then the feeling of retribution ought to be allowed to operate, and punishment should be inflicted, but it should in no case be out of proportion to the wrong done or the offence committed. This is with reference to the first form of revenge, that is to say, where the aggrieved person is able in his turn to inflict pain on the aggressor.

The second form which revenge might take in a case where the aggressor is a powerful man and the person aggrieved is unable or unwilling to inflict pain on him, is that of abuse and fault-finding. Concerning this the Holy Quran says, ‘Do not impute faults nor abuse each other.’16 Fault-finding and abuse are, therefore, prohibited in all cases, and even an aggrieved person should not have recourse to them in revenge. What is the reason underlying this prohibition? Why should not an injured person injure his oppressor by finding fault with him, and why should he not relieve his feeling by heaping abuse on him? The answer is that abuse is prohibited because it is false and immodest, and Islam does not tolerate falsehood or immodesty. Defamation and fault-finding are prohibited because, instead of reforming the conduct of the aggressor, they are likely to injure it, for, when a man’s vices are proclaimed openly he loses all sense of shame and decency and begins to indulge openly in them.

The third form of revenge is that the aggrieved party should cut off all intercourse with the offender. Islam disapproves of this form of revenge also. The Holy Prophet (sas) has said, ‘It is not permissible to a Muslim to cease speaking to his brother for longer than three days,’ i.e., he must resume speaking to him within three days.17

The fourth form of revenge is to entertain spite against the aggressor. This is also condemned by Islam. God says in the Holy Quran, ‘We have driven out spite from the hearts of the believers,’18 that is to say, a Muslim should not be spiteful. The Holy Prophet (sas) has said, ‘A Muslim is not spiteful, and does not harbour malice.’19 Islam, therefore, permits only one form of revenge and that is to inflict on a trespasser punishment in proportion to the wrong done by him, and even this is subject to the condition that if there is an established Government in the country, retribution must be exacted through the machinery appointed by the Government and the person aggrieved must not take the law into his own hands. If there is no Government, the punishment may be inflicted by the person aggrieved, but it must be in proportion to the wrong suffered; and if forgiveness is more likely to reform the offender, he must be forgiven. The other forms of revenge, that is to say, abuse, fault-finding, nursing of spite, etc., are all condemned by Islam, for they tend to promote evil and discord, and the real object of vengeance, viz., the reform of the offender, is not achieved.

Another natural instinct of man is love which is again common to man and other animals. The opposite of love is hate. Both these natural instincts are converted into moral qualities by the use which is made of them. We can neither love everything nor hate everything; it is necessary to place restrictions and limitations on the working of these instincts.

We find that we naturally love those objects that are either useful to us or which yield comfort or pleasure to any of our senses. But this is not a moral quality, for such feelings of love are to be found among animals also. Love will be a moral quality, first, if it is exercised in proper proportion, that is to say, those who deserve a greater portion of our love than others should receive more of it, secondly, if it is based more on gratitude for benefits, received in the past; than on the hope of receiving benefits in the future, for the former is an obligation and the latter mere self-interest, and thirdly, if it has regard not merely to immediate benefits and pleasures but also to remote ones. When thus regulated the instinct of love becomes a moral quality, otherwise it is mere natural passion. Islam prescribes these three conditions. The Holy Quran says:

‘Say if your parents and your children and your brothers and your sisters and your wives and your husbands and your kinsfolk and the property which you have acquired and your business the dullness of which you fear, and your dwellings and your homes which you love, are dearer to you than God and His Apostle and striving in the path of God, then wait till God issues a decree concerning you, and God loves not those who forget their responsibilities.’20

This verse describes the gradation in which those who deserve our love are to be loved by us if our love is to be a moral quality and not a mere instinct. Each is to be loved in proportion to his or her proper rank in our affections. God is to be loved in proportion to his rank, and the Prophets, in proportion to theirs, and religion and parents and children and wives and husbands, in proportion to theirs. If that were not so, love would not be a moral quality but mere passion. For instance, if a man forsakes his parents for the sake of his wife, or ignores the call of his motherland for the sake of his property, he cannot be called good on account of his love for his wife or his property. He has, no doubt, loved, but his love is not controlled by his reason or his judgment, and is not, therefore, a moral quality.

The second condition is that it should have greater regard for past benefits received than for present enjoyment, or the hope of receiving benefits in the future. Under this condition love for one’s children becomes an instinct and love for one’s parents becomes a moral quality. The love of parents for their children is merely a manifestation of the instinct of preservation of the race, but the love of a child for his parents is a moral quality, for the parents have already done what nature wanted them to do, and now they are almost useless. A son, therefore, who loves his parents exercises a good moral quality, for he does so in remembrance of the benefits received by him from his parents during his childhood and in return for that kind and loving care he considers it a duty to treat them kindly and to provide every comfort for them even at the sacrifice of his own. That is why Islam has said, ‘Paradise is under the feet of one’s mother,’ and has not said, ‘Paradise is under the feet of one’s children,’ for every sane person instinctively loves his children, but every person may not instinctively love his parents, and, therefore, does not love them as they deserve. Instances are not wanting of persons who neglect their parents in order to provide for the smallest needs of their children. Nobody would say that this is a good moral quality.

The third condition necessary to convert love from an instinct into a moral quality is that it should have regard not merely to immediate benefits and enjoyments but also to remote ones. For instance, a man loves an object, but that love injures his faith or his morals. In such a case love would be a natural instinct but not a moral quality, for the consequences of such love are bad and not good. If a mother, out of love for her child, does not rebuke him for his faults, her love is merely an instinct and not a moral quality, for if it were the latter, the mother would have censured the child for his faults, and attempted to correct them, for the real good of the child is in being rebuked in such a case and not in being petted. In this connection the Holy Quran says:

‘O believers, real love is this that you should save yourselves and your wives and children from destruction.’21

Hate is another natural instinct, as opposed to love. The natural operation of this instinct is to repel or avoid those things that are useless or harmful, or those that are disliked. Some religions condemn the feeling of hate, and pride themselves on teaching high morals. No natural feeling is, however, to be condemned merely as such, as the use and application of such feeling, on the proper occasion, is to be commended and not condemned. What is to be avoided is the excess or diminution of such feeling above or below the proper standard. Excess of hate would be enmity, that is, an inclination born of dislike, which incites a man to acts of transgression towards the object of such dislike. On the other hand, lack of the feeling of hate on a proper occasion argues a lack of self-respect, that is to say, a failure to dislike a thing even when it offends against one’s sense of self-respect, dignity, etc.

Hate, therefore, is not in itself immoral; it is a mere natural instinct. It is only its improper use that is undesirable. For instance, the Holy Quran repeatedly condemns spite or enmity, and describes it as the quality of unbelievers and transgressors, and never ascribes it to the believers. At a few places enmity has been ascribed to God and the believers, but there it means the recompense of enmity and not enmity itself. On the other hand, Islam, just as it condemns enmity, disapproves of the feeling of dislike and hate being suppressed altogether, for they are the necessary supports of dignity, self-respect, etc., which are admittedly good moral qualities. How is it possible that we should regard a thing as evil and should feel no repugnance towards it? All evil is spiritual uncleanliness. When we see a man in a filthy condition or in dirty clothes, we feel a repugnance towards him, even if he is nearly related to us, and nobody would condemn this feeling of repugnance. Then, why should we condemn the feeling of spiritual repugnance which arises from our witnessing an evil deed? This feeling is to be commended, and when it is exhibited in its proper place and occasion it is a good moral quality.

In fact all this condemnation of hate and repugnance is due to a confusion between evil and the evil-doer. No doubt, we must care for and look after even the evil-doer, but we must also hate and dislike evil. If we do not condemn the evil of the evil-doer, we shall not be prompted to reform him. Islam has pointed out this distinction. The Holy Quran says:

‘Let not the enmity of a people incite you to injustice. Be just, that is nearer to righteousness.’22

In other words, one must be just even towards one’s enemies. Again, it says:

‘God does not forbid you to show benevolence to, and to deal equitably with those of your opponents in faith who have not made war upon you in order to compel you to renounce your faith and have not driven you forth from your homes.’23

That is to say, benevolence is enjoined even towards the enemies of Islam. On the other hand, at another place it says, ‘Do not lean towards the transgressors.’24 Now taking both these verses together the meaning is obvious, i.e., in temporal affairs you should show benevolence even to the unbelievers, but you should feel repugnance towards such of their acts as are contrary to purity and righteousness. At another place the Holy Quran says:

‘God has endeared faith to you and has made it attractive to you, and He has put repugnance in your hearts towards disbelief, disobedience and transgression.’25

These verses show that whereas on the one hand, Islam enjoins kind treatment and benevolence towards evil-doers, it incites, on the other, repugnance towards evil. Thus alone can morals be perfected.

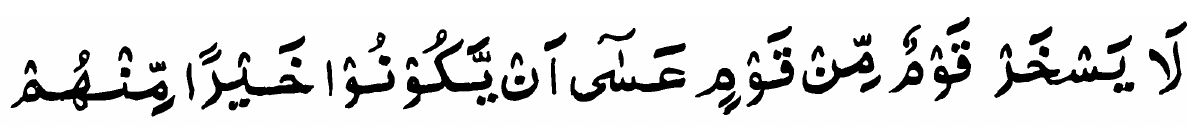

I next turn to the natural instinct of ambition. Man desires to outstrip his contemporaries in the race for progress. This instinct is not confined to man, but is also to be found among other animals. A horse going at a leisurely pace begins to gallop as soon as it hears the sound of hoofs behind it; and seeing this the one behind also begins to gallop in an effort to outrun the one in front. The proper use of this natural instinct produces many moral benefits, and a deficiency or excess of it results in many moral defects. A man can derive great moral advantage from it by using it as an aid in moral and spiritual development. For instance, the Holy Quran says, ‘O believers, outstrip one another in virtue and good deeds.’26 It is by virtue of this instinct that a student makes rapid progress in his studies. When used under proper restrictions and limitations, it develops into an excellent moral quality.

On the other hand, the unrestricted exercise of this instinct gives rise to many undesirable qualities. For instance, it produces envy, that is to say, a desire to advance accompanied by a desire that nobody else should advance. Islam condemns this feeling. One of the prayers taught in the Holy Quran is, ‘I take refuge with God from the mischief of an envious person.’27 Another moral defect produced by an excess of this instinct is that a man begins to despise the merits of others, and begins to look upon them as positive faults. In Arabic this feeling is called Ihtiqar (scorn). Islam condemns this feeling also. For instance, the Holy Quran says:

‘O believers, let not one people despise another, haply that other may be better than themselves, and let not women despise other women, haply the latter may be better than the former.’28

If the feeling of scorn continues to develop, the scornful person begins to abuse other people or to taunt them concerning their descent or origin, etc. Islam has forbidden all this. For instance, the Holy Prophet (sas) says, ‘Whenever a man imputes to another a moral or a spiritual fault which does not in fact exist (that is to say, when the imputation is by way of abuse or defamation), the same fault will manifest itself in the man who has made the imputation.’29 A further consequence of the uncontrolled working of this instinct is that it renders a man proud and boastful; he gradually forgets his own faults and weaknesses and begins to consider himself superior to everyone. Concerning this the Holy Quran says, ‘God loves not him who is proud and boastful.’30

Another natural instinct is the instinct of propagation of the race. Islam has imposed necessary restrictions and limitations on it also, so as to convert it into a moral quality. For instance, the Holy Quran says, ‘Marriage is lawful to you.’31 But, ‘Approach not adultery,’32 that is to say, do not seek to satisfy your passions outside lawful wedlock, otherwise the object of this instinct, viz., the propagation of the race, would be defeated. Those, however, who cannot find a suitable match are told:

‘Those who cannot find mates should preserve their chastity.’33

That is to say, they should take such precautions as would enable them to keep a strict control over their passions, but they should neither commit adultery nor deprive themselves altogether of the power of propagation, for God does not approve of the total suppression or uprooting of a natural instinct. In this connection the Holy Quran says:

‘Some people have devised celibacy and monasticism to keep their passions in check. We did not prescribe these things for them, they are their own inventions and (being contrary to the natural instincts) they were not able to observe them as they should have been observed.’34

This shows with what consummate wisdom Islam has regulated the working of this instinct. On the one hand, it has provided a legitimate means of satisfaction through marriage, and on the other it has prohibited its satisfaction outside lawful wedlock. It disapproves of celibacy, for a strict observance of it would amount to a total suppression of this instinct, whereby the object for which this instinct was created, namely the propagation of the human species, would be defeated. If celibacy were to be adopted generally, the human race would become extinct in the course of a generation. As the practice is contrary to nature, those who devised it were not able to act strictly up to it. As to those who cannot find suitable matches, Islam exhorts them to preserve their chastity till they succeed in finding a mate but does not permit them to destroy the instinct altogether. Is there any other religion which regulates the working of this instinct common to man and all species of animals, including insects, so as to convert it into a high moral quality, based on deep psychological truths?

Another natural instinct in man is the exercise of his rights of ownership over property whereby he spends his wealth or hoards it. The working of this instinct has also been properly regulated by Islam.

The first restriction imposed is, ‘Spend out of the best of that which you have earned or are entitled to (and not out of that to which you are not, entitled).’35 Again,

‘And give to those relatives for whose welfare you are responsible their rightful share in your property’ (indicating that Islam enjoins a man to look after his near relatives), ‘and to the poor and the needy and give not with a view to receive a profitable return, nor squander the whole of your substance.’36

The Arabic word, Tabdhir, means to scatter seeds or to scatter away, or to prove or test a thing. The expression, La tubadhdhir tabdhira, in the above verse, therefore, means that a man should not give to relatives or the poor or the needy in the hope of, or with a view to receive from them, a larger amount in return, as a farmer scatters seeds in the hope of gathering a rich harvest; nor should a man give away all his substance and keep nothing for himself, or conversely, squander all of it on himself and give nothing to others; nor should he give to his relatives and the poor in such a manner or in such quantities as to render them idle or to encourage in them the habit of begging or living on charity, or to lead them into dissipation, and thus to make the giving a means of temptation rather than of assistance to them.

Again, the Holy Quran says,

‘In a Muslim’s wealth those who can express their needs and those who cannot speak and express them (i.e., animals) have a right.’37

A Muslim must, therefore, spend a portion of his wealth for the care of weak and sick animals, whether domestic, vagrant or wild.

Similarly, Islam has laid down detailed instructions concerning all the moral qualities, for instance, patience, gratitude, beneficence, righteousness, trust, loyalty, confidence, moderation, providing for the needs of others, care of widows and orphans, promoting goodwill among men, fear, hope, contentment, selflessness, brotherhood, meekness, endurance, modesty, fulfilment of promises, benignity, dignity, hospitality, visiting the sick, honesty, probity, sorrow; and the moral evils, backbiting, slander, falsehood, mischief, eavesdropping, espionage, reading other people’s letters, cheating, proclaiming one’s beneficence, doing good with a desire that it may be heard and seen by men, hypocrisy, idle talk, swearing, flattery, theft, murder, oppression, rebellion, torture, using with false measures, interference, cowardice, etc., etc., the observance or avoidance of which tends to promote righteousness and purity. It is obvious that it is impossible for me within the limited scope of this paper to deal in detail with all these moral qualities. I need only remark that Islam has, by this process of limitation and regulation, converted every human instinct into a high moral quality, and that no other religion, whether prior or subsequent to Islam, has paid adequate attention to this aspect of the question. Even those religions which had the example of the Holy Quran before them have failed to solve this problem. It is only the Holy Quran that has solved it in a complete and satisfactory manner. Other religions have contented themselves with an enumeration of the natural instincts of man or of some aspects of them and have given them the name of morals. Islam has provided us with the most satisfactory solution of the problem which has for so long vexed and still continues to vex thinking minds, viz., what is the true significance of morals? Islam defines morals as the co-operation and coordination of the natural instincts of man. That religion alone can be credited with having provided us with a code of moral teachings which devises means for the proper working of every natural instinct, subject to such restrictions and limitations, as would operate to prevent any of those instincts from trespassing into the domain of any other instinct. Revenge should not interfere with the proper working of pity, nor should pity overstep its limits and interfere with the proper working of retribution; love should not interfere with hate nor hate with love; each should operate within its own proper sphere without colliding with any of the other instincts, like planets moving in their respective orbits. The operation of human instincts under the moral teachings of Islam may be described as a state governed by reason in which the citizens, that is, the natural instincts of man, are kept in order by the moral teachings of Islam.

I now turn to the second question arising under the second object of religion, viz., what are the different stages of moral qualities prescribed by Islam? The graduation of moral qualities is as indispensable to the moral development of man, as the graduation of courses of study is indispensable for the normal instruction of the human mind. If courses of instruction prescribed by our schools, colleges and universities were not divided into grades and classes, most students would be unable to derive any benefit from them. Many of them would not be able to decide how far they should proceed in a particular course of instruction and many would be discouraged at the outset, believing that it was impossible to accomplish that which had been prescribed. The institution of classes and grades, therefore, is not only convenient for teachers and directors of studies, but is also of great benefit and encouragement to the students. The same is the case with moral instruction, or, for the matter of that, any kind of instruction which is meant for the universal benefit of mankind. It must be so graduated that people of varying attainments and capacities should be able to take advantage of it. If the course is so regulated that only people of high attainments can take advantage of it, it will be of no benefit to people of average or low capacities and vice versa. If, on the other hand, no order or arrangement is kept in view, people of ordinary attainments and capacities will be unable to derive any benefit from it. Again, if it is a mere collection of imaginary and high sounding moral precepts, it will be of no practical use or benefit to mankind, except for the purpose of adorning a speech or impressing an audience. Mankind, therefore, is in need not only of a code of moral teachings, but of a practical and graduated code, which can lead men to moral perfection through a gradual process.

I now proceed to explain the different grades or stages of moral qualities, good and bad, prescribed by Islam.

Islam has laid down both categorical and detailed rules governing the moral conduct of man. It has divided good and bad moral qualities into different stages and grades, whereby each man can check and determine his own moral position and carve out a way for the acquisition of good qualities and the discarding of evil ones. In addition to this basic or fundamental classification which covers all moral qualities, Islam has described each moral quality in detail, and has laid down a perfect order which governs all these qualities.

The fundamental classification of moral qualities is contained in the verse:

‘God enjoins equity, beneficence and treatment like that between relatives; and forbids evils which concern the individual alone and are not manifest, and those that are manifest and offend the feelings of others, and those that injure others. He admonishes you, so that you may be rightfully guided.’38

In this verse virtues and vices are divided into three classes respectively, and these six classes cover the whole field of moral qualities.

The first stage of virtue is ‘Adal or equitable dealing, that is to say, a man should deal with others as he is dealt with by them, and should repay the good done to him with at least an equal measure of good. He should also think equitably of others, that is, he should think of others as he desires that they should think of him. He should not repay good with evil nor expect from others good in return for evil. The word ‘Adal however, excludes all such evils as are absolutely undesirable, for instance, abuse, falsehood, adultery, etc. ‘Adal permits man to mete out punishment to an offender in proportion to his offence, but does not permit him to seek to punish him (the offender) by doing in his turn an evil act similar to the one done by the latter, for vice is a poison, and a man who takes poison himself in order to punish another for having taken poison, commits an act of folly and not of revenge.

The next higher stage of virtue is Ihsan, i.e., beneficence, that is to say, a man should try to repay the good that is done to him by another, whether that good affects property, body, or mind, by a larger measure of good, and that he should forgive those who trespass against him, except in cases when forgiveness would promote disorder and strife. This stage is higher than that of ‘Adal and a man cannot attain to it unless he has first habituated himself to the first stage, otherwise it will only be a superficial transformation, liable to be reversed in a moment of aberration.

The third stage of virtue is described as Ita’i dhil qurba, that is to say, a man should do good to others neither in return for any good done to him nor in the hope of receiving good in return, as for instance, parents do good to their children, or brothers do good to brothers, under a natural impulse. Parents do not love or look after their children in the hope of receiving benefits from them in return. Even in the case of parents who are too old to expect that they would be alive by the time the child grows up, there is the same fondness and love for the child as in the case of parents who are still in their youth. This love of parents for their children, as I have said, is not prompted by any hope of gain; it is an instinct. Parents never imagine that they are laying their children under any sort of obligation by loving them and looking after them. They only fulfil a natural yearning and the hope of a material return or the thought that they are laying the child under an obligation never even enters their minds. This feeling, therefore, which parents or near relatives entertain for their children or relatives is much nobler than Ihsan or beneficence. In beneficence there is a certain feeling of self-complacence, a feeling that one is doing a good act, whereas in the love of parents or relatives for children and relatives, there is no such feeling of doing good to others. On the contrary, there is a feeling of relief and pleasure personal to one’s self. This is the highest stage of virtue, and a man who attains to this stage derives a genuine pleasure from doing good. He does not imagine that he is laying anybody under an obligation. Rather he feels grateful that he has found an opportunity of doing good, just as a man to whom a child is born does not imagine that a burden is laid upon him, but is happy and grateful for this Divine blessing. Such people devote themselves to the service of humanity, and find sorrow and joy in the sorrows and joys of others, and the thought never crosses their minds that they have conferred any benefit upon others. Instead, they are grateful that God has, out of His pure grace, afforded them opportunities of serving others. They constantly desire that they may be afforded greater opportunities of such service, as parents desire that if they had ampler means they would keep their children in greater comfort.

There are three stages of evil, corresponding to the three stages of virtue. As against ‘Adal there is Fahsha’, which, when used in juxtaposition with the word Munkar, means secret vices which are not apparent for instance, evil thoughts and evil designs issuing out of an unclean mind. This is the first stage of vice, as ‘Adal is the first stage of virtue. The influence of evil company, evil instruction or animal tendencies is first felt by the mind, and a man is assailed by evil thoughts which incline him towards vice. But there is an inherent tendency in man towards virtue which suppresses and overcomes such thoughts. If they are allowed to take root they prevail in the end and the first foundations of vice are laid. Then begins the second stage of vice, Munkar, which affects a man’s acts and conduct. Other people are displeased by such conduct and disapprove of it, but so far it remains confined to acts which affect the individual alone, for instance, loose talk, falsehood, etc. At this stage a man develops only a few vices, is ashamed of them and is afraid to indulge in more serious ones. If, however, he fails to keep a sharp lookout over his own conduct and takes no steps to check his career of vice, he arrives at the third stage, which is called Baghyi, that is, vices which injure other people and amount to an open violation of rules of moral conduct. The word Baghyi means revolt, and the third stage of vice, therefore, indicates that the evil-doer openly revolts against moral laws and throws off his allegiance to them. He now takes pleasure in vice, and boasts of it, and reproof and admonition are lost upon him.

By indicating these different stages of virtue and vice, Islam has rendered it easy for all persons to ascertain their true position in the moral scale and to take steps and adopt measures for their moral improvement. At every stage a man has a definite object put before him, which does not appear to him to be impossible of attainment and which, therefore, does not discourage him. For instance, nothing would appear stranger or more hopeless to a man who is so steeped in vice that he does not possess the slightest conception of virtue or morality, than to be told that he must so reform himself as to make virtue a part of his nature and to spend the rest of his life in the service of humanity. The gulf between his present position and that which he is asked to attain to, would appear insuperable, and he would probably despair of ever becoming a reformed man. But if he were to be told that every step taken towards virtue makes him more virtuous and that if he can not altogether renounce vice he should at least feel ashamed of it, he would eagerly follow the suggestion as being practicable and easily attainable. When he begins to feel remorse and is ashamed of his conduct, he can be told that he has achieved the first step towards virtue, for the renouncing of the graver forms of vice is also a form of virtue. The encouragement which he derives from this can be used as an aid towards his further progress on the path of virtue. He can next be told that if he is yet unable to do good, he should at least avoid evil, and should refuse to act upon the evil promptings and suggestions of his mind, so that he should not by his evil deeds cause pain or unpleasantness to others. He will find this easier than the first stage, and when he has accomplished this he will be more than ever eager to advance towards virtue and to renounce his former career of vice. His mind will still be liable to evil thoughts, but, can anybody doubt that he will have attained a certain stage of virtue, for he will be constantly advancing towards it and will have renounced the greater portion of his vices? He may then be asked to take the next step and to cleanse his mind of evil thoughts and to shun all impurity and vice. This will surely be much easier for him than the first two stages and when he has accomplished this, his mind will be like that of a new-born child, a clean slate on which no impression has yet been made. He shall next be asked to adopt the standard of ‘Adal or equitable dealing in his conduct, and thus he will gradually attain to that stage of virtue for which he is fitted by his courage and capacities.

If this method is not adopted, every scheme of moral reform is bound to end in failure. General moral sermons which do not keep in view the principles here enunciated, are of no value as means of effecting moral reform. One might as well start the education of an illiterate child by asking him to commit to memory the books prescribed for a post-graduate course, or to memorize the whole of the New Oxford Dictionary, in the fond hope that when he has performed this stupendous task he will become a truly learned man. The result will be that the child will probably go mad, or at least his mind will be left as blank as when he started. He will only have retained a few phrases in his memory, which he would be able to repeat like a parrot, without having the slightest notion of their meaning. In the same way, no moral improvement can be effected by exhortations, however fine, of a general nature.

A person who receives his moral instruction in this general manner will pick up his morals from his companions and his surroundings, and will derive no benefit from the moral instruction which is lavished upon him.

The Holy Quran lays great stress upon this graduated course of moral training, so much so that it says, no man can be a Prophet unless he teaches men to become Rabbanis. Rabbani means a person who gives instruction first in elementary matters, and then in more advanced sciences and arts, and regulates his course of instruction by dividing it into grades and stages. It is necessary, therefore, for a Prophet to impress upon his followers that in prescribing courses of spiritual and moral training, they should have due regard to the capacities and temperaments of those who are meant to be benefitted by them. They should persuade people to give up their old habits step by step, and should instruct them in those things of which they are ignorant, by degrees. Gradual instruction does not, however, mean that some things should be kept back as secret from some people, but that people should be instructed to act upon those things step by step, so that they should always have in view an object which is easily attainable, that they should not lose courage, and that their successful accomplishment of one stage should be an encouragement to start on the next. For instance, all scholars are aware of the total length of the course which they have to go through, but its division into classes and grades and the frequency of tests and examinations serve as encouragement to them so that they are able constantly to measure their progress in studies and, thus, do not feel oppressed by the idea of having to complete the whole course at once.

In addition to these general instructions, Islam lays down detailed rules concerning each moral quality, and prescribes grades and stages, which render it very easy for a man to adopt or renounce desirable or undesirable moral qualities as the case may be. But as the space at my disposal does not permit me to enter into an explanation of these details I shall content myself with what I have said concerning the general division of moral qualities, hoping that this would be sufficient to indicate the nature of the moral teachings of Islam.

In regard to this question also Islam lays down certain principles, and supplements them with certain details. The principle is:

‘I have not created men—great or small—but that they should develop in themselves My attributes.’39

The first object of moral development, therefore, is to fit man for union with God, for, unless a man purifies himself he cannot approach the Source of all purity and life. God loves not the wicked and the impure of heart, and desires that men should assume His pure attributes, so that they might be fitted to approach Him. He says:

‘We have created on earth the most beautiful and useful things and have appointed men therein to see which of them conducts himself most beautifully,’40

That is to say, which of them develops Divine attributes in himself. So that the reason why some moral qualities are called good is that they are reflections of Divine attributes, and the reason why others are called bad is that they are inconsistent with Divine attributes. That which has no share of the light must surely be dark; and the farther it recedes from the light, the darker will it grow.

Apart from this general classification Islam has in the case of different moral qualities assigned detailed reasons which demonstrate the good or bad nature of each of these qualities, so that people may be drawn towards those of them that are good, and should avoid those that are evil. I shall here mention some of those details by way of illustration.

I have already stated that one of the highest moral qualities in man is the quality of pity which manifests itself in forgiveness. In addition to the general reason stated above why this quality should be regarded as good or noble the Holy Quran states:

‘When a man injures and oppresses you and deals unjustly with you, you should deal kindly by him and forgive him. Thus will you strike at the root of hatred and enmity, and he who is your enemy will become your fast friend.’41

Punishment is generally inflicted to prevent the wrong-doer from committing further wrongs. Islam says that if the principle laid down by it were followed, viz., that the person injured should forgive the wrong-doer where there is reasonable hope that forgiveness would help to reform him, greater benefit would result from it than from the imposing of a penalty. Punishment would, at the most, avert further injury, but forgiveness is likely to convert the wrong-doer into a friend.

Again, in regard to beneficence and benevolence the Holy Quran says, ‘Do good to others, and let them have a share in your wealth, your knowledge and your power, etc., for, has not God been beneficent towards you?’42 That is to say, God Who provided you with the means and with the capacities by which you have acquired wealth, knowledge, and power; and as all mankind are sharers in the bounties of God, you should, in return for the favours granted to you, let other men share in the things with which you have been blessed.

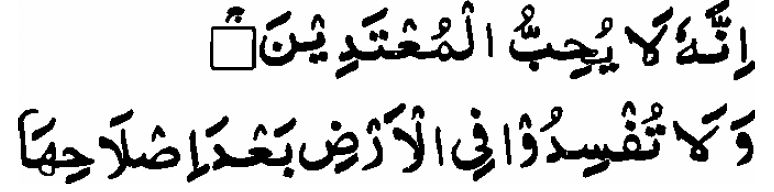

As regards murder and oppression it is stated that they lead to further disorder and oppression, and that mankind would become extinct if they were not checked. The Holy Quran says:

‘Avoid oppression, for God loves not oppression, and do not by oppression create disturbance in the earth after peace has been established therein.’43

That is to say, oppression never promotes peace and order. It is never a source of strength, for it creates agitation and a determination in the people to resist it, and conspiracies and rebellions destroy the peace of the land.

Concerning envy the Holy Prophet (sas) says, ‘Avoid envy, for envy eats up the sources of comfort, as fire eats up fuel.’44 That is to say, you are envious of another because he is in greater comfort than you, but envy takes away your own peace and comfort, and thus you only injure yourselves.

Concerning contempt the Holy Quran says:

‘Let not a people despise another people, it may be that the latter may become better than the former.’45

In the revolutions of the wheel of time it may be that a people who is despised today may be honoured tomorrow, and a family that is honoured today may be despised tomorrow. If a people is looked down upon today, tomorrow when they attain to power, they are sure to seek to humiliate those that looked down upon them, thus setting in motion a vicious circle of hatred and disorder. When the field of improvement and progress is without discrimination open to all God’s creatures, why should a particular nation or class or section be despised?

With regard to adultery and fornication the Holy Quran says, ‘It is an impurity and an evil way.’46 That is to say, it is a vice which produces a sense of secret guilt in the mind and renders it impure and it is a wrong way of achieving the object underlying the sexual instinct. The object of this instinct is the propagation and preservation of the human race. Illicit intercourse defeats that object by preventing birth or by rendering the parentage of the child doubtful and thus putting its care and bringing up in peril.

Concerning miserliness the Holy Quran says:

‘Some of you are miserly, and he who is miserly is miserly to his own prejudice.’47

That is to say, a miser only deprives himself of the use of his wealth. He deprives himself of the enjoyment of eating good food, wearing good clothes, and living in a good house, etc. He goes on hoarding money, and the only enjoyment which he gets out of it is the added care and anxiety of keeping it safe.

Thus Islam gives reasons for commending or condemning different moral qualities, and enables people to judge of their nature.

The function of religion is not merely to point out good and bad moral qualities, but also to provide or devise means by which men may be able to renounce evil and adopt good morals, for without this all our effort is vain and our search profitless. I am unable to say what the answer of other religions is to this question, but I am happy to be able to state that Islam or Ahmadiyyat furnishes a complete and satisfactory answer to it.

The first means of moral improvement furnished by Islam is through the manifestation of Divine attributes, without which the attainment of moral perfection is impossible. In all things man stands in need of demonstration; he can easily learn through demonstration what he cannot acquire through books. In the absence of demonstration all sciences and arts would be lost to the world. For instance, can anyone learn chemistry or engineering or any other science without the aid of experiments and demonstrations?

The same is the case with moral training. Man cannot attain to moral perfection without the help of perfect models and demonstrations. It is necessary, therefore, that perfect models should appear again and again in the world to demonstrate to mankind a life of moral perfection. It is also necessary that these models should themselves be men for a being that is not human cannot serve the purpose of a model for men. The conduct of such a being cannot encourage mankind to imitation. So we must have perfect men to imitate and such men must appear from time to time to enable other men to mould their conduct in imitation of them. Islam claims that such perfect men appear frequently on earth. For instance, the Holy Quran says:

‘O, Sons of Adam, whenever I raise from among you apostles who relate to you My signs, then those who learn righteousness from them and help them to reform the world, shall suffer neither fear nor grief.’48

Apart from Prophets, there are other persons who may also, though to a lesser degree, serve as models for the people. Concerning these the Holy Prophet (sas) says,

‘God will raise among the Muslims, at the beginning of each century, men who will renew the faith by excluding from it false doctrines and beliefs which may have crept into it, during the course of the century.’49

Such reformers have constantly appeared in Islam. In our own age when the darkness of error had become intense, God raised a Prophet for the protection and restoration of the faith, and for the renewal for the benefit of mankind of the perfect example of the Holy Prophet (sas). Hundreds of thousands have found new spiritual life through this Prophet.

This is the only complete and perfect means of attaining to moral perfection. All other means are only subsidiary to it. The advantages of this are certain, but those of others cannot be entirely free from the possibility of doubt and error. As, however, this means cannot be procured by man at his own will and pleasure, Islam has provided other means, by which a man might discard evil morals and acquire good ones.

The second means provided by Islam for the moral improvement of man is the method adopted by it in classifying moral qualities into different grades and stages, with which I have already dealt, and which need not, therefore, be repeated here.

The third means provided by Islam for this purpose is that it has explained the reasons why good moral qualities should be adopted and evil ones eschewed, so that men, knowing the real nature of these qualities, may of themselves be prompted to acquire good morals and to eschew evil ones. This has also been explained above.

The fourth means provided by Islam for this purpose is that it has altered man’s point of view in respect of evil morals; it has substituted hope for despair. Many evils are committed because they can no longer avoid them. Those who propagate such ideas among their children, lay the foundations of the moral depravity of future generations. A man who does not believe that a certain object is attainable, will never strive to achieve it. A people that believes that its forbears have exhausted all possible discoveries and inventions is not likely to make a discovery or invention itself; and a nation that believes that it cannot possibly effect an improvement in its condition is not likely to attempt it. Similarly, people who believe that evil is inherent in them and that they cannot possibly resist it, and that it is impossible for them to achieve moral perfection, provides the means of their own destruction. The Holy Prophet (sas) has laid great stress on this point, and has altogether forbidden despair. He says, ‘When a person says the people have perished he is the person who destroys them.’50 That is to say, no material calamities and misfortunes can prove so disastrous to man, as the conviction in his mind that the door of improvement and progress has been shut upon him. Despair prevents a man from making an effort for success and thus leads him to certain failure and destruction. Islam does not countenance the view that man can ever be debarred from self-improvement and progress, and thus opens wide the door to moral development. The Holy Quran says, ‘We have created man with the best capacities.’51 That is to say, he is endowed with the highest faculties for development and progress. Again it says, ‘Let the creation of the perfect and blameless soul of man which is endowed with the faculty of distinguishing between right and wrong, bear witness.’52

There can be no doubt that man is born with a pure and sinless nature, and however deep he might plunge into sin, his nature retains some of its original purity, so that if at any time he turns towards virtue, he can discard all his vices, which are all acquired, and can attain to the perfection of virtue, which is inherent in him. By proclaiming this truth Islam has completely altered man’s point of view towards good and evil, and has furnished him with fresh hope and courage. Religions other than Islam are either silent on this point, or represent man as entering this life under so many burdens and handicaps that they are enough to drown him without the additional weight of his own misdeeds.

Islam says that man is born pure. This helps him to keep up his courage and to try to preserve his nature unsullied. If he believes that he is born sinful, he would not mind so much if he were to become a little more sinful than he already is.

But to be born with a pure nature is not enough. Before a man attains to the fullness of reason he has to walk along a path beset with dangers of which he is not aware, and the temptations and base desires that he encounters sometimes sully the purity of his nature. If there were no method by which such stains could be washed away, man would plunge into despair and would make no effort to regain his original purity. Hence, in order that moral improvement should become possible religion must provide means for effacing the stains of acquired sin. Islam claims to have made provision for this by opening to erring men the door of true repentance, which has been closed by all other religions. Islam rescues man from despair and tells him that he can, in spite of errors and mistakes, attain to that purity of mind and conduct which is the highest goal of man. It thus encourages him to make constant efforts towards virtue and purity, and enables him ultimately to arrive at his goal.

Some people imagine that the doctrine of repentance encourages indulgence in vice, as a man can go on committing sins in the belief that he can at any time repent and thus escape the consequences of his evil actions. No sensible person, however, would entertain such an idea, for how could he be certain that he would be afforded the opportunity to repent? Besides, the objection is due to lack of appreciation of the true nature of repentance. Repentance is not so easy as these people imagine. It is not open to a man to repent at any time at his own will and pleasure. Repentance is a spiritual revolution which changes a man’s entire moral and spiritual being. It means true and abiding remorse for past sins and errors, and a firm resolve to make one’s peace with God and to reform one’s course of conduct. This condition cannot be brought about at will. It is the outcome of continued effort and contemplation. In very rare cases it may be the result of a sudden emotional upheaval but such emotion would be produced only by some volcanic action shaking the very foundations of a man’s being, and such action could not be generated at will. Repentance cannot, therefore, encourage indulgence in vice; it is a true means of effecting reformation. It saves man from despair and encourages him to make efforts towards self-improvement.

The idea that repentance encourages wrong-doing is due to the misapprehension that repentance means merely to ask forgiveness for one’s sins. This however, is not repentance (Taubah or Istighfar). Repentance does not mean asking forgiveness for sins; but on the contrary, sins are forgiven as the result of repentance.

The fifth means prescribed by Islam for moral reformation, appears at first sight to be inconsistent with the fourth, but in reality it is merely supplementary to it. This is the effort which Islam makes to uproot the evil influences of heredity. No doubt man is born with a pure nature, but he sometimes inherits from his parents or remoter ancestors certain inclinations towards vice. This is not a self-contradictory statement. Nature and inclination are two different things. Nature or conscience is always pure.

Even the child of a robber or a murderer is born with a pure nature. But if the parents possess an evil mind, the child will be influenced by it, and if he subsequently encounters evil situations, will be easily led away by evil thoughts just as the children of confirmed invalids are prone to fall an easy prey to diseases from which their parents suffer. Such inclinations and tendencies of a child result from the thoughts which fill the minds of the parents at the time of their union. The effect of these thoughts on the mind of the child is, in most cases, very slight and may often be overcome by environment and training, but Islam has prescribed a means of turning even such influences into instruments of good.

The husband and wife are taught to offer a prayer when they are together, which means, ‘Secure us, O Lord, and our issue against evil thoughts, evil promptings and evil companions.’ Apart from its efficacy as a prayer, the invocation starts a current of pure thoughts in the minds of the parents, even if they are not ordinarily responsive to them. Not merely the act of praying but the words of this particular prayer, as well as the concern which most people feel for the welfare of their issue, and the natural desire of all parents that their children should lead pure lives, combine to produce this effect. When, therefore, parents offer a prayer for the purity of their children, their own minds are bound to be affected by it and to incline towards purity and virtue; and as the child is likely to inherit the thoughts entertained by his parents at the moment, he will be saved from the influences of all such evil thoughts which his parents may have entertained prior to this prayer. The Holy Prophet (sas) says : ‘Children whose parents offer this prayer at the time of their coming together are saved from the touch of Satan,’ meaning, that they are saved from the evil influences which they were liable to inherit from their parents.

The sixth means provided by Islam for the moral improvement of man is that it has devised ways for such thoughts to enter the mind of man as to incite and stimulate his natural instinct of virtue. Some of these ways, e.g., prayer, worship, fasting, remembrance of God, etc., have already been mentioned, and need not be repeated. I shall, however, describe three of those ways that have not yet been mentioned.

The first of these is mentioned in the following words of the Holy Quran, ‘O, ye Muslims, keep company with the righteous.’53 It cannot be denied that man is influenced by his environment, and a man who keeps company with the righteous is bound to experience a rapid and wonderful change in himself which draws him towards virtue and helps him to get rid of vices and evil thoughts. Islam lays so much stress upon the influence of a man’s company upon his morals, that Muslims have always been fond of resorting to the company of righteous men. They often undertake long and arduous journeys for this purpose and bear separation from their homes and dear ones, and by the help of the magnetic influence of such men arrive at their goal within a wonderfully short period of time.